On May 2, 1845, William Cooke’s Royal Circus came to Great Yarmouth, a seaside resort town on the eastern edge of England’s Norfolk County. To stimulate interest, the circus scheduled a spectacular opening event: Nelson the Clown would float in a tub along the rivers linking one end of town to the other, pulled by four geese. Thousands of people headed down to the riverbanks to watch, with the densest crowd assembling on the suspension bridge at North Quay, where the clown and his geese would complete their voyage.

Nelson entered the River Yare near Yarmouth Bridge, driving his avian team north, through the tidal lake of Breydon Water, and out into the River Bure. As he neared the home stretch, some four hundred-odd people cheered him on from the suspension bridge. Nelson waved and grandstanded, his geese honked and swam, and the entire crowd pressed, en masse, against the balustrade to get a good look as he passed below.

Their collective weight and momentum proved too much: the suspension cables snapped, the bridge came tumbling down, and everyone was tipped into the water. Seventy-nine people, including fifty-eight children, died in what would become known as the Great Yarmouth Suspension Bridge Disaster. The May 10, 1845, edition of the Norwich Mercury called Nelson’s stunt a “foolish exhibition” and went on to wonder: “Oh! Who shall paint the one mighty simultaneous agonizing death-scream which burst upon the affrighted multitude around—re-echoing from earth to heaven—may the appeal not be made in vain.”

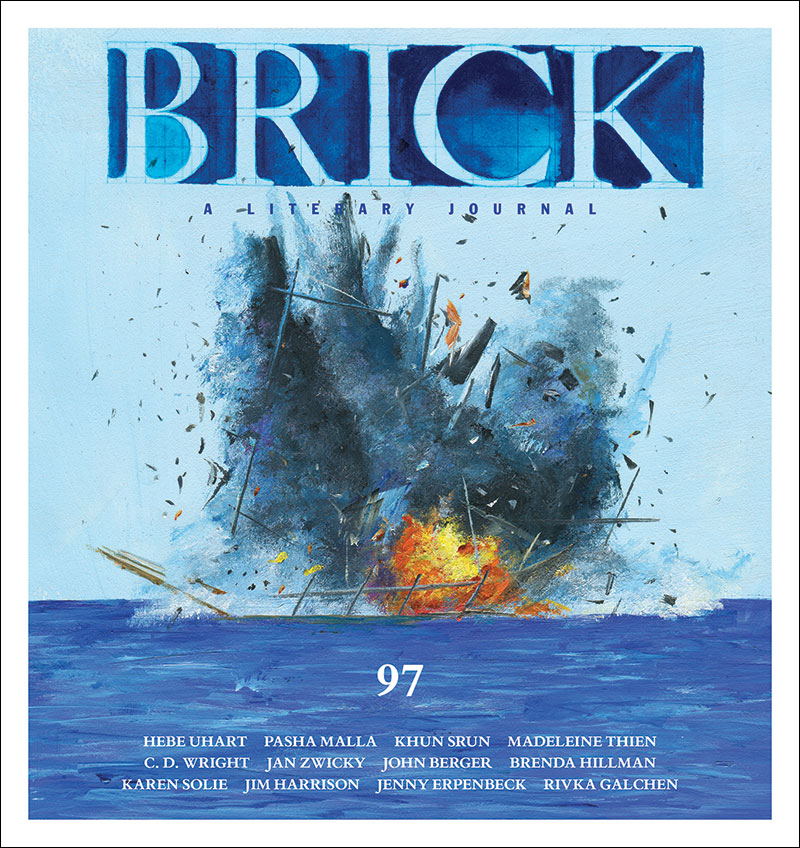

The appeal was heeded. Paintings and drawings of the disaster, of which there are several, capture the chaos after the bridge has caved into the river: the water teems with bodies; intrepid rescuers are doing their best. Interestingly, none of these images depicts Nelson the Clown among the swarm.

When you hear this story, where do your sympathies go? To the children. To their parents. To the town itself, decimated by catastrophe. Maybe you have your own kids and think about them falling into the water, crushed by corpses and debris. Maybe you imagine yourself drowning; maybe you have a fear of such things. Maybe you even fancy yourself a hero who’d haul survivors onto the riverbank.

Me, I think about Nelson, who survived. What guilt he must have lived with. How might he have ever hitched himself to waterfowl again? I picture him living out his days forlornly sitting for ironic portraits. The truth, however, is that Nelson was unrepentant; afterwards he continued performing this identical stunt for years. So I wonder, might I have done the same thing? If, say, something I wrote were somehow responsible for the deaths of dozens of children, what else could I do but try to redeem myself by conjuring joy for dozens more?

On the handbill for Cooke’s Circus, Nelson is described as a “low comedian.” But a comedian, low or high, is still an artist. And part of what an artist does, I think, is to forge connections with and between other people. The greater the number of people connected, the more accepted and worthy the artist might feel—and, by some metrics, the more valuable his or her art. So I think that, like Nelson, most artists would be pleased to have packed a bridge until it buckled. Perhaps the resulting catastrophe even explains why Nelson kept performing: less as restitution than from the distinction that people had literally lost their lives to see his act. Which is to say that he continued clowning not in spite of the Great Yarmouth Suspension Bridge Disaster but because of it.

And yet. I wonder about this instinct to make one’s work, and oneself, so broadly appealing. Maybe it’s good to fill a bridge until it collapses. Yet I doubt how fundamentally each soul is touched in a crowd, which generates its own attendant enthusiasms—of participation, of inclusion, of groupthink and mob rule. Surely some folks on that bridge in Yarmouth didn’t care about Nelson at all but had simply come along to be part of something, or not to feel excluded. And fair enough. Life can be lonely and alienating, and communal experiences are hard to come by.

While Nelson was able to transcend culpability and go on to a successful career, were he to exist now, it’s possible that his celebrity wouldn’t generate from his stunt with the geese but from the catastrophe they caused—the scene of disaster rather than the one of entertainment. The modern clown, after all, is most often that poor, otherwise anonymous soul who debases him- or herself in the limelight. It’s worth keeping in mind, too, the plea from the Norwich Mercury beseeching artists to paint something not simply as commemoration but to help understand the horror. But, in a culture of infamy, what if the artist’s role is not to sublimate and transmute spectacle but to produce it?

Imagine a work of art that draws no audience to the bridge—not a single person. This performance or exhibition or publication would be so intrinsic to the creator that it speaks to no one else on earth, and as such need not be witnessed or documented; its mere realization would be its own imperative, and that would be enough. If this had been the case with Nelson, seventy-nine lives would have been saved. But then I guess I wouldn’t be thinking about him now.

Maybe the secret is to aim for only one person—but to really isolate the point of connection, some deep intimacy so fundamental it can be shared only, at most, between the artist and a single patron. Imagine one child who admired Nelson the Clown more than anything and anyone. Let’s call this person Sophie; let’s say she’s nine. After reading about him in the Norwich Mercury, on May 2, 1845, Sophie can’t wait to witness Nelson perform his signature, remarkable feat of sailing down the river behind a team of geese. And yet, she is the only person in town who intends to watch, so Sophie feels lonely and wonders why no one else shares her reverence for such a splendid entertainer. It makes her feel bad for Nelson too.

Regardless, after school that day, Sophie goes home and changes into her prettiest pinafore and makes her way down to the river promptly for 5 p.m. All of her feelings of alienation fade as she walks to the middle of the suspension bridge. Instead of loneliness she feels anointed, the sole recipient of a great and wonderful gift. Giddy with anticipation, she longs for the moment when the little convoy will emerge from Breydon Water and come curving around the bend onto the River Bure.

As the sun begins to nudge the western horizon, the geese appear, followed by the bathtub gliding slickly over the water. Nelson! As he passes the train station, he lifts a hand to acknowledge Sophie some fifty yards upstream. Delighted, she waves back. The geese churn resolutely forward. Sophie watches, rapt, as they approach. Finally they are so close that she can hear the tub gurgling and see Nelson’s grin. And then they’re gone, tucking beneath the bridge and leaving only a fan of wake carved into the water. Sophie scampers to the bridge’s north side. She leans over the railing, gazing down at the space where the geese will emerge—it’s real, it’s just for her, it’s happening!

Pasha Malla is the author of five books. Fugue States, a new novel, will be published in May 2017