A lot of life is left in the man being killed.

He does not at first foresee the end. He knows, of course, that anything can happen. When it begins, his only worry is that he will be unable to work. At the very least, he thinks, he will be unable to lift heavy loads. He has used his hands all his life. They are his tools. He had himself made the door of the room from which they dragged him out.

Then it settles in as disappointment. He had so much more work to do in the unfinished house. The iron rods striking him are raising dust from a ground sown with regret.

He knows he can list the names of the men, whose voices he recognizes in the dark. A few from the dinner in his house only two nights ago. He will repeat the names to the police, he tells himself, before losing consciousness for a minute.

Or more.

He comes back to life when he hears a child’s voice asking if the man is dead. Is he? One man’s voice, and then another’s, sending the child back inside. The child is a stranger, but the man being killed would like him to know that he is alive. It has been a long time since he made a sound. He tries to speak without scaring the kid, without crying. It comes out like a moan, and immediately a boot, no, a brick, smashes into his face.

He tries to focus elsewhere. His chest is home to an excruciating pain and he suspects broken ribs. His pain keeps him in the present. Death, or the possibility of his dying, comes to him when he notices that, despite the pain and the wild commotion, he has slipped into a dream.

He remembers being in the classroom when he was ten. They had read a poem. The teacher was newly wed. He can see her now, a fresh flower every day in her hair. The poem was about a warrior dying, dreaming of his homeland on the alien battlefield. The teacher had liked him. She stopped coming to school when she was going to have a baby.

Unlike the warrior, he is dying in the dark lane outside his house.

A friend of his had died five years ago from dengue. During his final hours, the friend had thought his mother was still alive, sitting with him in the shabby hospital ward. Mother, he called out, I want water.

The reason he thought of his friend just now is that he is thirsty. His uncle used to keep a pot of water under the neem tree. He wants a drink. As a child, he would look up after taking a sip and see parakeets bursting out from under the canopy of green leaves.

He thinks of a nephew, dead at thirteen, killed by a bus when on his way to school. Compared to that poor boy, he has lived a full life. Despite all the fears that parents are prone to, his children grew up into adulthood. If they survive tonight—his daughter was left cowering in the room upstairs, his son left for dead with his head split open—they will be able to fend for themselves even if he is absent from their lives.

They have stopped hitting him, or maybe he can’t feel anything anymore. His eyes are swollen shut. Is it still night? He wants it to end.

He has stopped telling them they are wrong. Now his tongue is like a small animal running in one direction and then another. When he starts babbling, their blows fall. Blood is pooling under his head. But what is he saying? It is garbled speech, a line from a prayer his father used to recite, even when he yawned, mixed with words he had heard a lawyer speak—was it the veteran actor Dilip Kumar?—in court in a black-and-white Hindi film on TV.

A sudden new pain like a million ants crawling up his leg. He thinks the men are setting him on fire. No, they are only dragging him up the steps onto a lighted platform to make WhatsApp videos of the dying man.

Out of great weariness comes a new change. He feels he is walking away, able to cover a vast distance, without any real effort of his limbs. In the shadow of a boulder that blots out the hot sun, there is silence.

The man being killed has never seen the sea. But he hears its wide sound now in his ear, and this would be magical if it were not so real. So real that he can taste the salt of the soft waves.

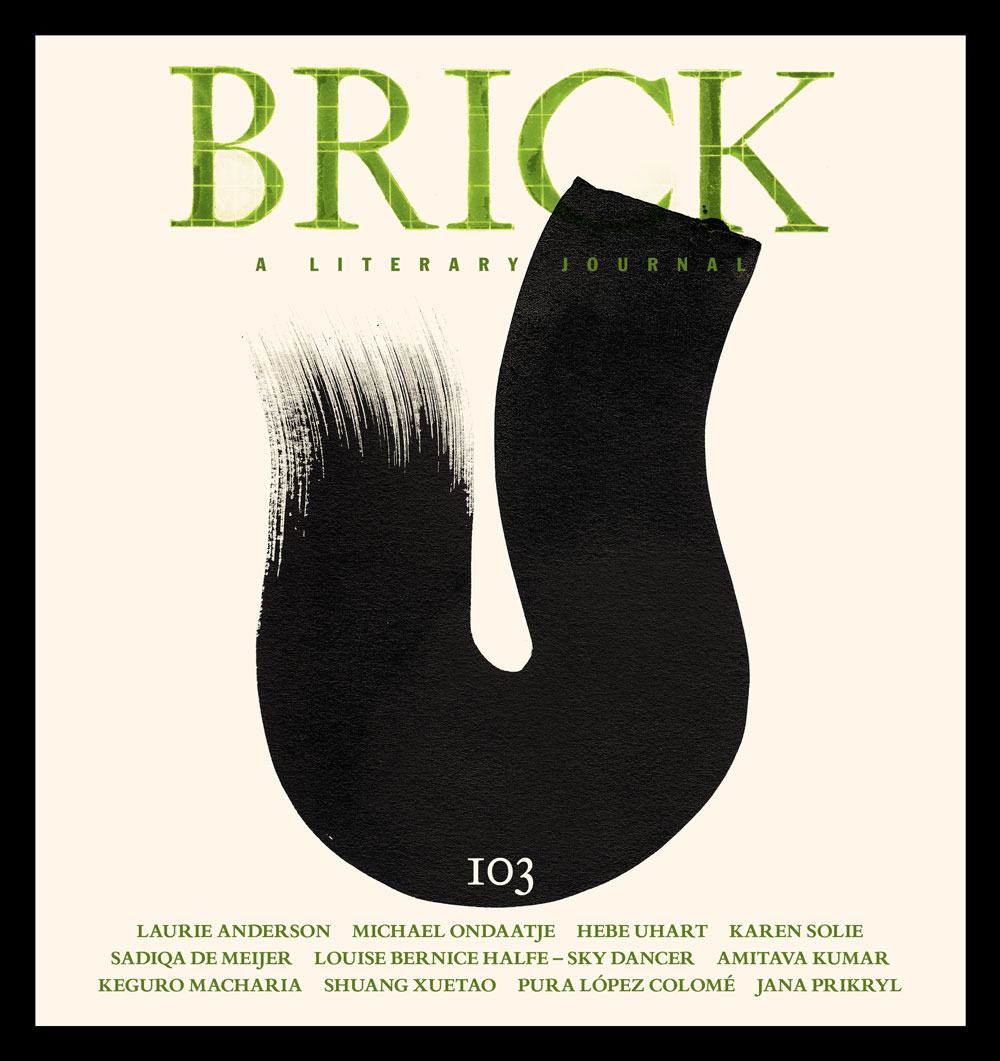

In a little bit, it will be cocktail hour. This beautiful villa stands on a hill, the sloping ground covered with small olive trees and long lines of tall, angular cypresses. In the few days I have spent here, this is what I’ve discovered: one sure way to stop visiting fellows and their spouses from talking to me during cocktail hour, or the dinner afterwards, is to answer them truthfully when they ask what it is I’m doing here. I give my answer and see the light die in their eyes. They nod and look elsewhere—the lake, for instance, which looks lovely at all hours, its colour changing constantly. I don’t blame anyone. Would you want to talk to someone who says he is studying models of social acceptance? But what I mean simply is that I’m examining who in our communities will accept lies and deception. As in all matters, all my projects seeded in guilt, I find myself culpable. But on this issue I have certain others in my sights. This evening, holding my glass of chilled, locally sourced wine, I’d like to be able to tell my interlocutor that the question I’m asking is this: Who among your neighbours will look the other way when a figure of authority comes to your door and puts a boot in your face?

During his last week in office in January 2017, President Barack Obama gave an interview to a book critic from the New York Times. Obama told the interviewer that his daughter Malia had read Ernest Hemingway’s A Moveable Feastand was captivated by the writer describing his goal of writing one true thing every day. (“All you have to do is write one true sentence. Write the truest sentence that you know.”) When I read the interview, Trump had been president for two days, and I think the idea for this piece of writing was born then.

Later, a friend posted on Facebook a few lines from a poem by the radical Hindi poet Gorakh Pandey. My friend was aiming to describe the situation in India under Modi, but such lines don’t characterize only a single society. I read the extract and that same morning sat down to translate it. In my writing journal, I made a note that this extract would serve as my epigraph:

King said it is night,

Queen said it is night,

Minister said it is night,

Guard said it is night.

This happened right

This morning!

Do you remember the days immediately after Trump took office? Loud fans in places such as Cincinnati, Ohio, or Des Moines, Iowa, or Mobile, Alabama, had found the freedom to behave like frat boys on a Friday night. Republicans were greeted with chants of “U.S.A.! U.S.A.!” There was a spike in assaults against Blacks and Muslims and others who, to Trump loyalists, looked like outsiders. But the Women’s March took place on January 21, the largest single-day protest in the nation’s history. The American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU) declared its readiness to challenge Trump’s executive orders and witnessed a spike in membership as well as donations. The New York Times published an ad to highlight the fight over truth, which ended with the words: “The truth is more important now than ever.” The online Merriam-Webster dictionary also took up the good fight; after Trump aide Kellyanne Conway described false statements as “alternative facts,” Merriam-Webster sent out the following tweet: “A fact is a piece of information presented as having objective reality.” (On January 22, 2017, when I saw that tweet, it had been liked 55,914 times.)

Yesterday, during cocktail hour, my choice of drink was the Aperol Spritz. At first I spoke to a British man who was working to solve the water crisis in Gaza, particularly the salinization of the coastal aquifer and the threat this posed to the people living in one of the most densely populated strips of land there. Then I chatted with a Black woman from New Jersey who was composing music for a film. Nikki had studied violin at Juilliard and gone on to Stanford for another degree in ethnomusicology. I asked her what Stanford was like, and she laughed and said that she had once played with Condoleezza Rice. But she had been back in New Jersey for nearly two decades. Nikki was the co-founder of an organization that supported music and the arts. I said I had an odd question for her: Had she ever heard anyone say they had seen Arabs in New Jersey celebrating the September 11 attacks?

She said, Other than Donald Trump? No.

I said that he claimed he had watched thousands and thousands of people cheering when the Twin Towers fell.

She said, Lies. He lies.

I sipped my Aperol. Nikki was drinking white wine. I had started her on a new train of thought. She asked me if I had been living in the United States for long. I told her I had come from India in the early nineties. Nikki said that I probably didn’t know about the Central Park Five. In the late eighties a woman who had been jogging in Central Park was badly beaten and raped. She was unconscious for several days and unable to recall any details of the attack. Five Black teenagers who were in the park at the time were wrongly convicted for the crime. Nikki told me that Trump, back when the news broke, had placed an ad in the New York Post demanding that the boys be executed. It wasn’t until a decade or more later that they received justice when the real rapist confessed in prison and his guilt was confirmed by DNA testing. Another decade would pass before the five, who were grown men now, received a settlement from the city that had imprisoned them as children.

Nikki said, They received $41 million. Largest settlement in the country’s history. But you know what kills me? That here is our president, an accused rapist himself, who was back then buying space for an ad in the New York Post. This country hates nothing more than its Black children.

At dinner the other night, a woman from Colombia was sitting beside me. She asked if I was the person working on fake news. I said yes and asked her name. Isabella, she said, adding that she was working on a conceptual art project about evidence. She had moved from Medellín to San Diego two years ago. I was going to ask her more about her work, but Isabella was already saying that there was so much information in the world today she felt overwhelmed. Even before she had finished her sentence, I asked myself if she was going to say overwhelmed. Her use of the familiar wording showed that we all read the same things, she in her home in San Diego and I wherever I happened to be at that moment and Nikki in New Jersey and everyone else everywhere in the world. We all read and thought and said the same things. Then Isabella made a comment that surprised me. A few years ago, she had come across an unforgettable line in a newspaper article: “Anyone reading this essay will accumulate more knowledge today than Shakespeare did in his entire lifetime.” I was a bit incredulous. However, Isabella was confident and said that I could google it. I did that later in my room and saw that she had got the quote right. But at the time, all I could say was that I doubted whether I knew more than Shakespeare. To begin with, language, and the huge gap between his vocabulary and mine. But Isabella was not bothered by my argument. She said that the sheer amount of information any person had in the internet age, including fake news, couldn’t possibly be rivalled by someone living even twenty years ago. I pondered this.

Our pistachio ice cream had been served in ornate green glass jars. We paid attention to our dessert before Isabella spoke again. She said, For instance, I read on Twitter this morning that a lioness mates up to a hundred times a day. She said she had wondered all day, locked up in her studio, if that could even be true. (Of course, I googled this detail too. And a website in Africa confirmed Isabella’s piece of information.) I laughed, not knowing the right answer, and Isabella said, Who’s the genius who dreams up this nonsense?

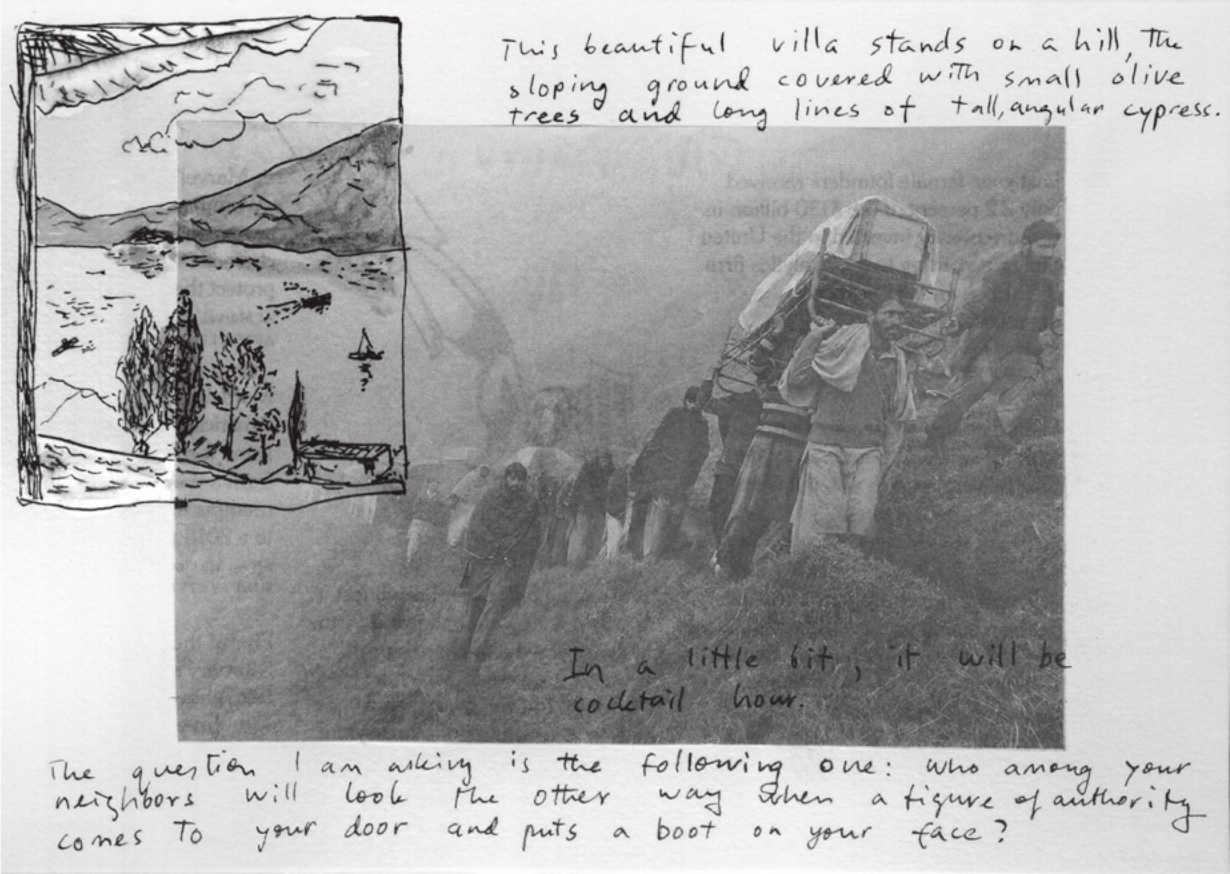

The semester is to start the day after I return to the U.S. I’m reading the first book on my syllabus, a novel described in a review as a report on the contemporary everyday. I put the book on the syllabus without having read even a page. The narrator is a writer married to a poet. She believes that the only reason to be an artist is to be able to bear witness. “Kathy dug it, even as she felt the numbness moving up her body. The speed of the news cycle, the hyper-acceleration of the story, she was hip to those pleasures, queasy as they were. People got used to them, they depended on the reliable shots of 10am and 3pm and 7pm outrage.” Fair warning. I have felt in myself the hunger for each new bit of news about a lynching, a hunger also for fresh evidence not just of cruelty but of the crime’s uniqueness.

If you are from India, you perhaps share a memory, which is a collective memory, which means you know it even if you didn’t experience it. An animal’s head is thrown inside a place of worship. By late evening, a part of the city has gone up in flames. The engineering of public violence through the manufacture of rumours.

Bhisham Sahni’s Tamas opens with a scene of a government official paying an untouchable man to kill a pig. The animal’s head is thrown on the steps of a mosque that evening. The untouchable realizes he has been made an unwitting accomplice to a riot. Sahni is constructing a secular critique of what in the subcontinent we call communal politics.

Nowadays it is all happening on WhatsApp, the Facebook-owned instant-messaging service. About two hundred million Indians are WhatsApp subscribers, making India the biggest market for the social-media platform. WhatsApp is free and easy to use; it consumes less data than Facebook or Twitter. Journalist Snigdha Poonam has reported that “Indians produce the majority of the 55 billion WhatsApp messages sent every day,” covering the gamut from family photos to political propaganda. Poonam adds that while WhatsApp is “the primary source of news for Indians,” what is circulated in the guise of news is often fake. I believe this makes Indians the biggest consumers of rumours or fake news. Poonam’s conclusion is more sober: “The consequences can be deadly,” she writes. “Rumours spread over the service are killing people in India.”

In my hometown in India (but this is true not just of that town), the atmosphere outside the jail on the day those accused of murder or rape or rioting are released is like a wedding. These men are guilty of everything they have been accused of, but because they have power or money, they are able to walk free. Car horns blare. There is music, also slogans, taunts, insults, and, of course, sweets. The foreheads of the victorious are smeared with red tilak. They raise their arms to quiet the crowd, join palms to show gratitude. If by any bad luck a girl from a minority community happens to be crossing the street, she is offered sweets, and if she says no, someone grips her arms while someone else thrusts the sweet inside her mouth before wiping his hands on her chest.

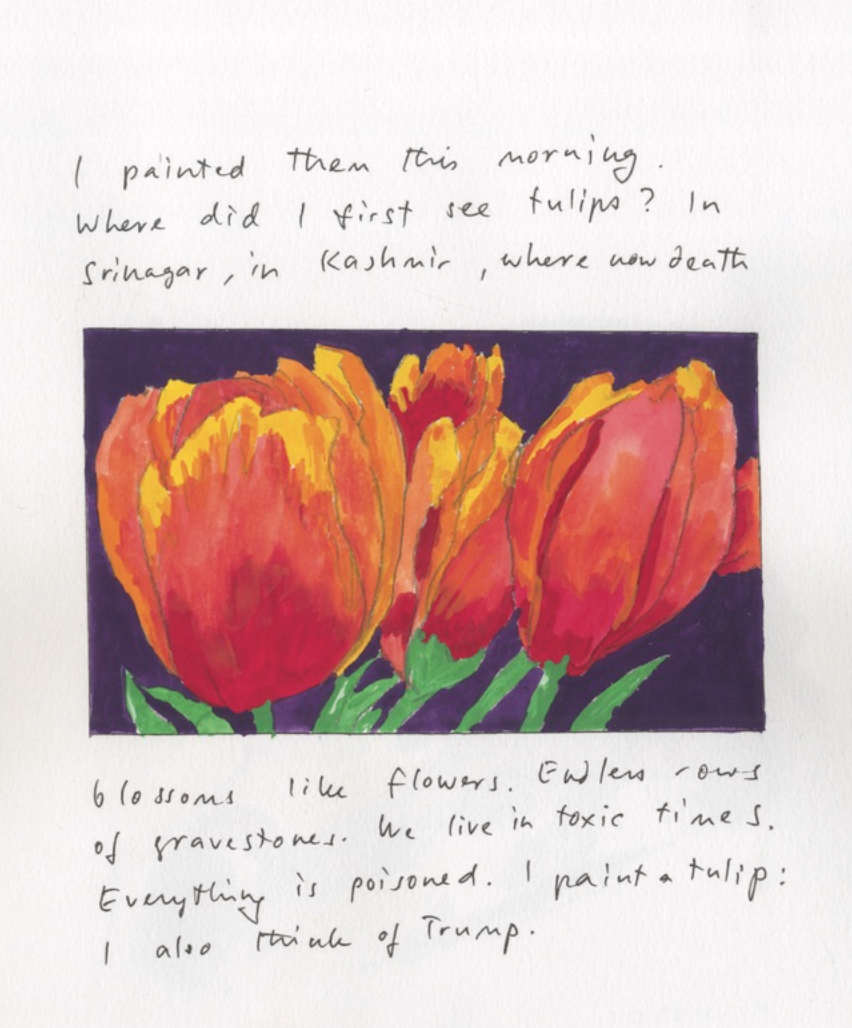

The truth is that the truth is complicated. Here’s a story, a terrible story, from the summer of 2017. Eid was around the corner. In Kashmir, in the part ruled by India, on the night the faithful observe Shab-i-Qadr, or the night the Quran is believed to have been revealed, an image of a badly beaten man clad only in his underwear began circulating on social media. His name was Mohammed Ayub Pandith. He was fifty-seven. The next day, the police released a statement that Pandith, deputy superintendent of police, had been assaulted and killed outside the Jamia Masjid in Nowhatta. Reading the news, I sensed the reporter’s frustration at being unable to parse the truth. Pandith was also a Muslim and a Kashmiri, like the men in the mob who murdered him, and in the end that is the angle that the reporter settled on. “Kashmiris are killing Kashmiris.”

But, as I said, truth is more disturbing. According to police, Pandith was tasked with frisking worshippers as they streamed into the mosque in Nowhatta where a prominent separatist leader was to lead the prayers. One version of events had Pandith getting involved in an altercation with the youth who were shouting anti-India slogans. Pandith was photographing them. But how would this be possible? asked Pandith’s son. His father didn’t have a smartphone, only a basic Nokia phone. When he was attacked, Pandith fired three shots from his pistol and injured his attackers. The police chief praised Pandith’s action: he had aimed at the legs and not tried to kill those who were about to lynch him. One could say that at least one Kashmiri was not killing Kashmiris.

The incident appears to have happened close to midnight. When the images of Pandith’s bruised body were forwarded on social media, all kinds of rumours spread through the valley. There were claims the body was that of a non-Kashmiri who had come to kill the man about to lead the prayers. Another rumour described the dead man as someone from the intelligence bureau spying on the worshippers. A third, more insidious rumour, especially in the context of the Indian subcontinent, was that the man who was lynched was uncircumcised. In so many riots, so many stories, the difference between life and death as thin as a piece of foreskin. The reporter mentions talk of Pandith being an honest and humble man. He hadn’t grown rich like some other police officers.

Last night when I went to bed, I told myself I would write in the morning from the report I had kept with me about Pandith’s lynching. What kept me awake for a long time was the mention that when Pandith’s son went to the Police Control Room to identify his father’s body, he fainted. My mind kept going back to the fact that hours after the pictures of Pandith’s body first appeared on social media, another photograph was circulated on WhatsApp. It showed Pandith’s jaws with no teeth left attached.

So, this is what the human record comes down to.

Another resident at the villa is a filmmaker from Connecticut. She shared a bit of her work with us last week, and I got from her this quote that came from Pier Paolo Pasolini: “I don’t believe we shall ever again have any form of society in which men will be free. One should not hope for it. One should not hope for anything. Hope is invented by politicians to keep the electorate happy.”

Trump on the campaign trail: “I would build a great wall, and nobody builds walls better than me, believe me, and I’ll build them very inexpensively. I will build a great, great wall on our southern border. And I will have Mexico pay for that wall.”

And: “A Trump administration will stop illegal immigration, deport all criminal aliens, and save American lives.”

Also: “Donald J. Trump is calling for a total and complete shutdown of Muslims entering the United States until our country’s representatives can figure out what the hell is going on.”

As I write this, we are confronting the effects of such promises. Let me go back a few years to 2014, when Narendra Modi, the man who became India’s prime minister, was campaigning in the general elections. Modi wanted a ban on cow slaughter. He accused the party in power of promoting a “Pink Revolution” (pink because “when you slaughter an animal, then the color of its meat is pink”). The government, Modi said, boasted of India being the world’s leading meat exporter. Even in his earlier speeches, available on YouTube, you can hear him declaiming against the killing of cows: “Brothers and sisters, I cannot say whether your heart is pained by this or not, but my heart screams out in agony again and again. And why you remain silent, why you tolerate this, I just cannot understand.”

Speeches such as this were not about animal welfare. Modi’s words were an incitement for India’s Hindu majority, who mostly don’t eat beef, to turn against the minority, particularly Muslims, who are conventionally represented as beef eaters. (The number of people who eat beef in India—about eighty million—is larger than the population of Britain, France, or Italy.) Cow slaughter has long been banned in parts of India, but after Modi’s victory, frenzied mobs of vigilantes have felt emboldened to make accusations and mete out brutal punishment.

A year after Modi’s election, in a village about a two hours’ drive outside Delhi, a middle-aged carpenter named Mohammad Akhlaq had just finished dinner when a mob poured into his house. Akhlaq’s family were the only Muslims in the Hindu village, it was later reported. Earlier that evening, an accusation was made from a public-address system at the village temple that a calf had been stolen and slaughtered. The enraged crowd, led by the son of the local Hindu party legislator, cornered Akhlaq in his bedroom, where he was hiding with his daughter and one of his sons.

The assault was brutal. Akhlaq’s son was left for dead after his mother’s sewing machine was used to split his head open. Akhlaq was dragged out of the house by his legs and then beaten with bricks and iron rods. While he lay dying in the lane outside his home, some people recorded videos on their cellphones as others called him a Pakistani and shouted for his death.

Akhlaq’s killing was a crime, but by now most of those accused of his murder have been released on bail. Akhlaq’s lynching has revealed a sad truth about us Indians: while we will not kill cows, killing human beings is an entirely different, and entirely palatable, matter.

Akhlaq’s murder was followed by other gruesome deaths. Two brothers were stabbed on a train in Haryana State, in northern India, in a fight over seats. The victims, one of whom died, were Muslim; the men who attacked them had called them “beef eaters.”

The year before, in the same state, a Muslim woman who was gang-raped said that her attackers asked her if she ate beef; when she said no, they insisted she was lying.

In April 2017, a fifty-five-year-old dairy farmer named Pehlu Khan, who had just purchased five sets of cows and calves, was killed by “cow vigilantes” who accused him of smuggling cattle for slaughter. The killers acted with impunity, using smartphones to make videos of the assault; the police made some arrests after the fatal attack on Khan, but all the arrested individuals were Khan’s relatives, charged with cow smuggling. No one was arrested for murder until several days more had passed.

Two months later, Alimuddin Ansari, a Muslim meat trader, was pulled out of his van and beaten in Jharkhand State in eastern India. His van was set on fire. Ansari died on the way to the hospital. One of the main accused in Ansari’s killing was the man in charge of the ruling party’s media operations. When the eight men arrested for Ansari’s killing were released from jail, the Harvard-educated politician who was the local representative of the ruling party put marigold garlands around the necks of the accused men and fed them sweets. This happened in July 2018. The New York Timesin its report on the incident called 2018 “the year of the lynch mob in India.”

Another video, this one from June 18, 2018: Qasim, a Muslim trader who lived in a one-room apartment with his wife and children, can be seen half-sitting in a dry canal and asking for a drink of water. On both sides of the canal, young men are standing. No one gives him water and he falls over in the dirt, as if settling for sleep in his bed, laying one folded knee neatly atop another. It was later found that Qasim’s body had been pierced with screwdrivers and scraped with sickles. In the video, he is being accused of killing cows and you can hear people baying for his blood. An older man, also a Muslim, Samiuddin, comes forward to help Qasim. A young man is pulling Samiuddin’s beard, and then we see the older man being kicked in the stomach. His mouth is bloody. A pair of abandoned red slippers are lying in the field.

For their part, the police filed a report linking the assault to a motorcycle accident. Qasim’s relatives questioned the police narrative, which was further discredited when a journalist carried a hidden camera to a meeting with one of the main accused in the crime. The man said that people greeted him with loud cheers when he was released from jail on bond. He had never experienced such pride before.

What can you write that will make anyone reading you give a dying man a drink of water?

Amitava Kumar is the author of several works of non-fiction and a novel. His latest book is Immigrant, Montana. He teaches English at Vassar College. This is his third piece in Brick.