A photograph in an Irish newspaper depicts a member of the Garda Síochána shaking hands with his counterpart from the Police Service of Northern Ireland at one of the points where the territory of the Republic turns into that of Northern Ireland. The photograph, published in November 2015, seven months before Britain voted to exit the European Union, accompanies an article on plans for a “border corridor,” whereby police on both sides of the border can pursue fleeing criminals into each other’s region.

There’s a kind of joviality to the photograph: firm clasping of hands, big smiles. Behind the two men is the Irish landscape, rolling, misted, a river cutting through fields of green. The officers wear different uniforms, but the only obvious territorial demarcation, the only hint that they inhabit different countries, with different laws, health systems, and currencies, is a sharp change in road colour, from black to sudden grey.

I remember this non-distinctiveness, the dawning awareness that I had crossed a boundary, from the many trips I took to Northern Ireland between 2007 and 2010, when I worked on an essay that documented the systematic demolition of the Maze prison, a story that presented itself symbolically and—as it turned out—all too simplistically, as one of a settling of the past and a coming together for the future.

I never went North as a child. I remember a drawing in a newspaper depicting a map of Ireland. In the sliver of space that is Northern Ireland, the cartoonist had penned: “there be dragons.” In truth, it was worse than that. Ask me as a six-year-old, a twelve-year-old, about Northern Ireland and I would have responded: bombs and blood. Ask my young daughter today and she might look at you blankly. It means nothing to her, and that is a good thing.

There were ways it meant nothing to us too. I grew up in Cork, in the very south of Ireland, and that meant growing up a world away from bombs and blood. As children in the 1970s and 1980s, we were safe from soldiers in the back gardens, from streets we couldn’t walk down. But things filtered into our child worlds. From television: the dark loom of the watchtower, the helicopters, the aerial prison shots following the 1983 Maze escape; Gordon Wilson, who lost his twenty-year-old daughter in the 1987 Enniskillen bombing: “I shall pray for those people tonight and every night.” Of the few discussions in school, I remember one: the classmate who had relatives in Belfast, and her upset, her anger, at our fear, our distancing and distaste.

As I got older and travelled in Europe, the easy comfort of that distancing—you and I are not alike—was undercut. “So where did you hide the bomb?” a French colleague joked when I worked for a summer at a hotel in Munich. “Until I met you, I thought all Irish people were savages,” a German girl told me during my Erasmus year in France. This was the early to mid-nineties and everywhere I went, there it was. “We in Australia just can’t understand it,” said the visitor to my apartment in London. I still remember the insult of his bemusement and sincerity, as well as my own avoidance. As far as everyone on the outside was concerned, I was them and they were me. I knew better—I mean, was it not obvious?

The first time I went North was in 2000, two years after the Good Friday Agreement, after the Omagh bombing and the howl of anguish that went with it, after it became imaginable, almost normal, for me to drive in my tiny Southern-registered Fiat from Dublin to Belfast and back again as I researched a writing project on women working in politics in Northern Ireland. I was in my late twenties by then, and I wasn’t afraid in Belfast’s city centre, which had the same familiar department store names as any British or Irish main street; nor on the Falls Road, which wrapped me in a warm blanket of tri-colours and Celtic symbols; but I felt heavy and intimidated as I made my way up the red, white, and blue pavements on Shankill Road to the offices of the Progressive Unionist Party, hesitant to speak in the corner store lest I betray myself through the soft spill of my Southern tones. But then this dissolved too, and seven years later, when I spent time interviewing former prison officers at the Maze, as well as the residents who had grown up beside the prison, all from a Unionist background, the sing of my Cork accent felt more like a benign curiosity than anything traitorous or threatening.

“Merging is dangerous,” writes Rebecca Solnit, “at least to the boundaries and definition of the self.” Is that why we wrestle against it so? The border with Northern Ireland, once a site of blocked roads and lookout towers, has evaporated, at least on the surface of things, but it remains a place of struggle, of contest, a tussle between those who wish to take it one way and those who would move in another direction, either within the boundaries of a unified Ireland or into the space of clarity that tells us where we end and they begin. The amorphous situation that has existed along the border for nearly twenty years, a fudge that has resisted discrete categorizations and that we seemed to have found a way to live with, or live within, is under pressure in the wake of the Brexit vote, as the clamour to once again define what we are and what we are not, begins to accelerate. We look for the solace of certainty, of knowing if we are one thing or the other, rather than allow ourselves to remain within the complicated, messy space of the both/and, a state made possible by the exhaustion left after thirty years of violence.

Hannah Arendt had a particular view of merging. As she searched out a meaningful concept of a Jew’s place in the world following the sundering caused by the Second World War, she ultimately rejected a form of Zionism that connected citizenship to ethnicity and tethered both to the boundaries of the nation-state. On the other hand, she wrote scathingly of those European Jews who would assimilate, who would ape the Gentiles in an effort to find their way into the ranks of the human, who would, she wrote in disgust, become “good Frenchmen in France,” “good Germans in Germany.” Arendt, you could say, had been one such good German. As a child she did not know that she or her family were Jewish; she learned of her ethnicity only through the anti-Semitic taunts of children on the street. But it was the shocking stripping of her German citizenship as an adult in the 1930s that ultimately woke her to the helpless vulnerability of the assimilated Jew and formed her conviction that Jews must stand defiantly aloof from the boundaries of nationality, turning instead toward the belonging of the citizen; the belonging that attaches to full and complete membership of a political community; the belonging that confers the right to meaningfully speak, act, and be heard in such a community; the belonging that means inhabiting a territory without subscribing to an overarching identity narrative. “Refugees driven from country to country represent the vanguard of their peoples—if they keep their identity,” she wrote. Today her sentiments do not appear so different from those of Dina Nayeri, an Iranian refugee who received U.S. citizenship at fifteen and became a French national at thirty, and who wrote in the Guardian that she had lost interest in the need to rub out her face as tribute for these benefactions. “As refugees, we owed them our previous identity. We had to lay it at their door like an offering, and gleefully deny it to earn our place in this new country. There would be no straddling. No third culture here,” she said, although a third culture appears to be the choice made by Arendt’s beloved Heinrich Heine, at least as she described it, which was to live as both a German and a Jew rather than deny his Jewishness as the price of belonging. “He simply ignored the condition which had characterized emancipation everywhere in Europe—namely, that the Jew might only become a man when he ceased to be a Jew,” she wrote.

Arendt came out of a Europe that had, she witnessed, conclusively intertwined national rights with human rights, which left her as mistrustful of a national, bordered identity as she was of the “abstraction” of any solemn notions of the inalienable rights of man. Heine, the Prussian-born poet and literary critic, came of age in the early nineteenth century, an era of political instability and contentiousness in his homeland; his conversion to Lutheranism was reluctant, regretted, and carried out only as the price of “admission into European culture.” In the early years of the twenty-first century, there was a feeling—I had the feeling—that Europe, at least on some parts of its continent, had found its way beyond these aspects of its shattering history and was on the turn toward the global and the flexible. In 2002, when I lived for a time in Paris, I could board a plane in France and emerge in Italy, where I could retrieve my bags and leave the airport without showing any identification, without queues or questions. This identity-less travel, the result of the then seven-year-old Schengen Agreement and so opposite to my conditioned, normalized experience of waiting in dutiful lines, gave me the very real sense of being a human in the world. The continent of Europe—the part of it that now had a common currency and permeable frontiers, and even onwards toward the rapidly opening East—felt magical, enlightened even, as if we were all in this together. The distinctions between us, forged through cultural, religious, and geographic experience, appeared shapeless now. I could be both Irish and European; I felt that I could, as Arendt wrote, “speak the language of a free man and sing the songs of a natural one.”

But there was a “them.” From my window in Stalingrad, the quartier in the north of Paris where I lived from September to Christmas, I watched men in jeans and jackets congregate outside in the early darkness of the winter evenings, lining up in huddled rows on a Friday for weekly prayers. I looked on, curious—what are they doing?—before I understood. This was one year before the Iraq War, which fractured the Arab world, but already and for long years it was not easy to be Muslim in France, even if you were the French-born descendant of those who had come in the 1950s and 1960s as part of the first wave of migrant workers from northern Africa who stayed in search of a better life; even if you identified as both Muslim and French, as really all, or at least so many, of such descendants do, and as French civic society, with its emphasis on the primacy of the citoyen, encourages—in theory anyway. The exclus, they used to call them. The excluded. If I lived in Stalingrad today, the men across the street would no longer be there; in 2011, politicians banned the saying of street prayers in Paris following far-right protests about creeping Islamization. Instead, near the street I lived on, under the bridge where the metro station lay, there would almost certainly be tents and other makeshift shelters constructed by refugees from Iraq, Syria, Afghanistan, and elsewhere, part of a new and different wave of migration that, along with the 2008 economic crisis, has upended all of Europe. In 2002, I also went to Greece on a reporting assignment. There was no graffiti then comparing Angela Merkel to Hitler; today many in the desperately indebted country view the dominance of German capital as the source of their woes. In Italy, France, and Germany, a radicalized electorate now supports nationalist parties and looks at the European Union with deep suspicion. We were never all in this together.

For the moment, I can travel from Ireland to Britain without a passport. For the moment, I can drive from Dublin to Belfast without stopping, as the road melts from the N1 to the A1 and the white and black sign informs me that speed limits are now being monitored in miles rather than kilometres. (How different to John McGahern’s experience in the early 1990s, recounted in the essay “County Leitrim: The Sky Above Us”: “There are ramps and screens and barriers and a tall camouflaged lookout tower,” he said of the border crossing at Swanlinbar in County Cavan. “A line of cars waits behind a red light. A quick change to green signals each single car forward. In the middle of this maze armed soldiers call out the motor vehicle number and driver’s identification to a hidden computer. Only when they are cleared will the cars be waved through. Suspect vehicles are searched. The soldiers are young and courteous and look very professional.”) By the time I will have finished writing this article, British Prime Minister Theresa May will have triggered Article 50, and the movements I have become used to taking between cities and countries will have been thrown into confusion. Since the terrorist attacks of November 2015, France has been in a state of emergency that includes a firm policing of its borders. For more than a year and a half, commuters travelling from Malmö in Sweden to Copenhagen in Denmark had to present their IDs. Temporary border controls have also been introduced by Germany, Austria, and Norway. Merging is dangerous. Those hoping for a united Ireland—and I am surely one—forget this. On his blog, the journalist and Northern analyst Andy Pollak notes that Andrew Crawford, the former special adviser to current Democratic Unionist Party (DUP) leader Arlene Foster, used to go through reports from one North-South body removing the phrase “all-Ireland.” Perhaps the action of deletion helped Crawford forge certainty, was part of an attempt to make sense of how he existed in time and space. Forging certainty helps us all as we construct both story and identity in order to figure out how to live, but certainty, or at least a fixed destination, gets us into trouble too: we blind ourselves to possibilities, to the creative potential that lies outside of the either/or, to what can happen when we follow Arendt, say, or Deleuze, that great demolisher of dualisms, into the space of the non-being, the uncertain, the becoming.

In her photographic series Kinderwunsch, Ana Casas Broda depicts her body in thrall to those of her children, an artist willing to lose herself in conversation with flux, with change, with overwhelm. The photos are intimate and direct. Casas Broda often stares unsmilingly at the camera: a candid, life-worn Olympia, her pregnant body naked and big, uncomfortable-looking with her second child, or scarred and slack following fertility treatment and birth. In one of the images, her children have marked her face and torso with crayon; she both encouraged this and passively accepted the results. “I am their canvas: they play with me and change me,” she said in an interview. Kinderwunsch means “desire to have children,” and Casas Broda submits, it appears to me, to the terror and the unknown of that primal desire. She tumbles downwards, inwards. In the photographs, her children clothe her in tissue paper, they cover her in Play-Doh. “I see their scribbles on my body as a symbol of how motherhood has changed me,” she said. What she is really depicting is dissolution (of a former self), symbiosis—and something else. In some of the images, she and her children appear as one, interwoven, but there are others where she is alone, or they are indifferent to her: a son plays a video game as she lies naked on a couch, in between mother and person, neither here nor there, her body nonetheless relaxed, strangely at ease in the moment.

Around the time I began my Maze project, I was experiencing the greatest disintegration of self I had ever felt. Crossing the border from North to South represented moments of enormous exhilaration and giddy freedom: dazed as I was, when I lay in a border hotel without the baby, who had just turned seven months, I thought that I could see a way back to myself, that the place where I ended and the child began would somehow become obvious again, clearly defined. I was wrong about that: there was no going backward. There was no going forward either, at least not in the way I wanted or imagined. Since the birth of my daughter, I remain in limbo land, the borders of a self so carefully constructed over nearly four decades now shifting. She arrived and I disappeared, something like that anyway. The categories I had thought surrounded me have dissipated into confusion and nothingness, and that, if I think about it too much, can be terrifying. Did I turn into you, I used to ask her when she was a baby, or have you become me?

When Colm Tóibín walked the border between North and South in 1987, he bumped into questioning British soldiers; a blown-up bridge on a road that once led from Dublin to Enniskillen; and, in Derry, a march led by former DUP leader Peter Robinson, then in the ascendant. Tóibín feared opening his mouth during the march, lest the crowd (young men in the main, some drunk) spot him as a Southerner. Despite the disappearance of the island’s physical frontier, the hangover from these tensions remains. My friend, a middle-class Northerner from a Catholic background who has lived in Dublin for nearly twenty years, at times employs turns of phrase that leave me reaching for a Cockney rhyming slang dictionary. Yet she and I both use colloquialisms a person born in England will never have heard. Nonetheless, for a long time my friend was lost and lonely in Dublin, reluctant to move back to a society still undercut by a deep lack of trust but lacking solid ground in the cultural space of the South; she felt different. “I was different,” she told me, as I tried to grasp her feelings of statelessness. It’s not as if we are from different countries, I told myself, not really anyway. But the thing is, we are, both literally and metaphorically. The border has dissolved, but trauma, so deep, so wounding, cuts us off from one another, makes strangers of us in the same land, pulls me one way, pushes her another; trauma turns a society inward, and it has turned Northern Ireland, in the words of retired Oxford professor of Irish history Roy Foster, into more of its own little place than ever. What we have in common is this (and this is easy to write and hard to live): we are more the same than we are different.

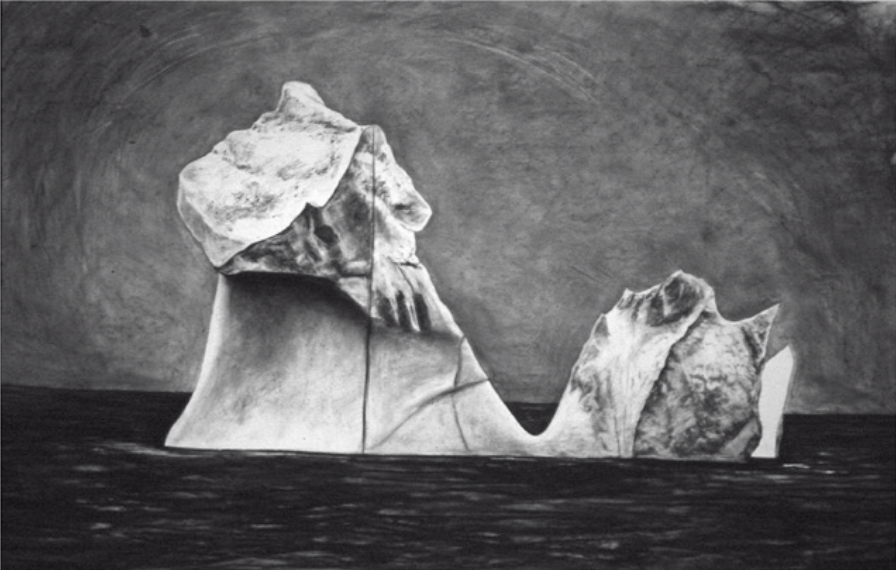

The artist Rita Duffy grew up Catholic in a largely Protestant area of Belfast; she is the progeny of a Southern mother and a father whose own father, a Catholic from the Falls Road, died at the Somme. Her two great-uncles on her mother’s side supported and may have been actively involved in the 1916 rebellion, which ultimately led to Irish independence, a civil war, and the fracturing of the island of Ireland. “I was continually fluctuating between nationalities, between identities, curious to know could I somehow land up in the middle somewhere that satisfied me today,” she told a symposium I attended in 2016. In recent years, Duffy has established herself within the space of the liminal: “I crept out to the edges of Ulster and we bought a little piece of the border. We built a house and I now have a studio just a mile and a half on the Southern side, and I live a mile and a half on the Northern side, so I kind of live in neither-here-nor-there land, which is a really interesting place to be as an artist. It’s very confusing and out of that springs the best imaginative possibilities for me.” Out of those imaginative possibilities have arrived big, bold ideas. The Titanic passenger liner was built in Belfast; the tragedy of its unfulfilled promise can be viewed as a metaphor for the long years the North lost to violence. In 2005, Duffy founded Thaw, a company set up to fund the towing of an iceberg from the Arctic to Belfast, where it would be moored outside the city and allowed to melt, in the process encouraging the shrinking of the deep, frozen divisions that still exist within Northern Irish society. Duffy has not yet found the means to drag her iceberg to Belfast, but since 2003 her paintings have been replete with the mythology of those hulking, frozen structures. She has created figurative images that appear trapped, encased in ice: Father Edward Daly, crouching, waving his handkerchief; a close-up of an arm, gesturing, holding a white handkerchief that may itself be an iceberg in miniature; in another painting, there is a Pieta, a mother holding a dying son, both emerging out of the bulk of an ice structure.

Duffy paints these images in greys and yellows, sometimes browns or greens, always muted. But in the middle, or in the distance, there is something, a speck of brightness, a blob, the white-grey of Father Daly’s handkerchief-iceberg, the light that draws your eye and that looks and feels like a breath of gulping air. If you thaw the frozenness, if you let it melt into the Irish Sea, then a space can open up, the iceberg no longer blocks your view and holds you in its frozen time. Behind you lies the city, with its plurality of people, before you the sky and the vastness of the ocean, deep and bold and cerulean blue. Duffy’s iceberg queen, a mammoth, back-turned Victoria, ascends into that blue, the blue of space, the blue of a possibility that allowed for an impossible friendship during the short time that former IRA member Martin McGuinness and the once-trenchant defender of Unionism, Reverend Ian Paisley, worked together in government in Northern Ireland. If you thaw the frozenness, a space opens up, and into that space walked Ian Paisley Jr., son of the good preacher, on various radio stations in January 2017, offering “humble and honest thanks” to Martin McGuinness on the occasion of the latter’s retirement.

In the North Atlantic, the largest iceberg on record was measured at 550 feet above sea level, the same height as a 55-storey building; less tremendous ice structures can still reach more than 200 feet high. The Titanic, travelling at top speed on a calm night, crashed into an iceberg that was more than a mile long and 100 feet high and had been growing into its dense mass of packed ice since the time of Tutankhamun, although once such an iceberg drifts from the Arctic to the warmer waters of the North Atlantic, which this one had, it will normally melt in two or three years. To an impatient human eye, this melting will be imperceptible until it is close to completion. My daughter likes to play with ice cubes; she takes them from her glass of water and lays them on the table, where she can contemplate their light, their translucence. When she first started this game, I watched benignly; these days I place a tissue or napkin on the table to soak up the water that spreads out so suddenly as the cube, whole only a moment before, turns liquid before our eyes.

In Bosnia, where I’ve been doing research, the iceberg is still solid, a mountainous whole that blocks ethnicities from seeing across to each other. The Bosnian peace deal of 1995 somehow managed to avoid the formation of literal borders; instead, the populace has retreated into different enclaves across the country, Muslims stick with Muslims, Serbs with Serbs, and so forth. The saddest example of this is Sarajevo, which now sits within the Federation of Bosnia and Herzegovina, one of two political entities that compose Bosnia. Sarajevo’s population is now almost 90 percent Muslim, many of them newcomers since the ending of the war; former residents, most of whom will never go back, mourn the city that was once multi-ethnic and cosmopolitan. Everything has changed, they will tell you, shaking their heads; the city is totally different. There is still separatist agitation, particularly in the Republika Srpska, the political entity that sits closest to Serbia proper, whose nationalist leaders threaten to form their own tiny state, but the frozen iceberg contains more than that: it holds the pain of deceit, of mistrust, of horrors, of loss, of history and geography, of denial and defence. Most of my time in Bosnia was spent in the Republika Srpska, in the east of the country, where I found myself crossing and recrossing the border with Serbia. At each crossing, I encountered the checkpoints: the wait, the documents handed over, the computer clearance, the questions on occasion, the stamps. My husband, a photographer, made the crossing alone once and was held for two hours while guards went through his equipment, his backpack, his wallet. The determined absorption of different religions and cultures into the shape of a single Yugoslavia after the First and Second World Wars had its problems too, but those Bosnians old enough to remember the time when the many amalgamated into the one speak of it wistfully, softly, as if it were a fairy tale they used to tell themselves as children. Their iceberg was waiting, biding its time out at sea, before it floated inland to lodge itself forcibly among them. The disappearance of the border between North and South Ireland has not sunk our icebergs. But over the past sixteen years, until the schism that was June 23, 2016, we had found ways to float one with the other, moored and not, comfortable and not, settled and not.

Is it possible to hold two contrary ideas at the same time: that sense that merging is both terrifying and monumental, the knowledge that we are all different, but that we live within a common world, that we can choose to be something and not? Although Alice Notley wrote that the birth of her child had left her “undone”—“feel as if I will / never be, was never born”—she could still see the other side: “Of two poems one sentimental and one not / I choose both / of his birth and my painful unbirth I choose both.” She hung in the balance, remained midway, gave herself over to not settling in. The child that was a baby when I began my Maze project recently turned ten and is in process, in transition. She is a self that I am not, although that self, according to Deleuze and Guattari, is only “a threshold, a door, a becoming between two multiplicities.” Her identity is no more fixed than mine is, than mine ever was, for all that I have scrambled to chase it. “What is real,” write the philosophers, “is the becoming itself. The only way to get outside the dualisms is to be-between, to pass between, the intermezzo.” There is confusion, and much relief, in such malleable thinking.

I was wrong, of course, in the assumptions I made about the Maze story. After the initial openness that followed the prison’s closure in 2000, when the paramilitary prisoners were let out and the public allowed in, political wrangling slowly strangled the goodwill until the great gates swung shut again; they have stayed shut, more or less, ever since. When I talked to people in and around the prison about politics and the peace, they felt bitter and hurt and sad, and that was not easy to hear. But any hard edges of fear or certainty seemed also to have blurred into a resignation that meant we could at least stand outside of compartmentalizations and inside the fuzzy space that doubt tends to uncover. Perhaps we could wait a while longer for the iceberg to begin its thaw.

It was almost always cold at the Maze; even during summer, the fog hung heavy over its vast flatness. When I was in need of warming, I would retreat to the small security hut at the entrance to the site, where a handful of guards took phone calls and processed visitors. What I recollect about these visits are the moments of recognition. One of the men, a gentle soul, English-accented, who had lost his wife too early and now lived a simple life of work and extended family, was the chatty type. I still remember how he once articulated my fear. “You dip your finger in a pool of water, swirl it about for a while, and when you take it out, the water will return to the way it was. Then it will be as if you never were.”

Rachel Andrews is a writer based in Ireland. Her essays have been published in outlets including n+1, the Dublin Review, and the Stinging Fly.