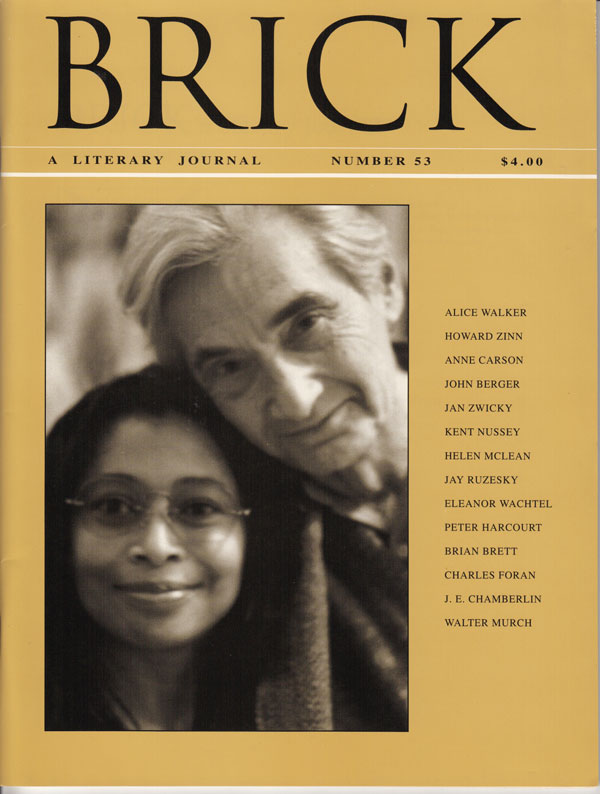

Alice Walker is the author of numerous books including The Colour Purple, In Search of Our Mother’s Gardens, and most recently The Same River Twice: Honouring the Difficult. Howard Zinn is the author of A Peoples’ History of the United States and You Can’t Be Neutral on a Moving Train. This conversation took place in San Francisco in January 1996, in front of an audience, as part of the Womens Foundation Collaboration with City Arts and Lectures.

HZ: I was Alice’s teacher! I remember the first day I met her, and I don’t remember the first day I’ve met every student. But this was Spellman College, Atlanta, Georgia, 1961. I’d been at Spellman for several years, but this was Alice’s first year. She’d just arrived from Eatonton, from out of the country.

AW: Deep country.

HZ: Deep country! And we just found ourselves sitting next to one another at this freshmen’s dinner or something like that—an honours dinner—Alice, you were honoured, even then! Gawd! Anyway, she was very quiet hut very dignified, not like now!

AW: I was sitting next to you!

HZ: We talked a little. And then, as a sophomore, she took my course. In a little college, you teach everything—things you know, things you don’t know. I was teaching a course in Russian history. I thought I would jazz it up a little with art, literature. I had students read Russian literature. Alice didn’t say anything in class. Then her first papers came in and she wrote this paper on Tolstoy and Dostoevski. I read the paper, and . . . well I showed it to a colleague of mine—this is sort of an inside thing about the academic world . . . I have a lot of inside things about the academic world. . . .

AW: I know you do!

HZ: And this colleague of mine, and with that professorial elegance he said: “She couldn’t have written that.” Alice, I never told you this, did I?

AW: No! Who was he?

HZ: We’re going to hear a lot of things tonight that we never told one another! Even though we’ve seen one another over the years. But there are things we haven’t told one another. He said, “Somebody else must have written this.” I said, “No. You’re wrong. There’s nobody around—who can write like this!” That was our introduction.

AW: I took your class because I had been to Russia the summer before, and felt very—I was really right out of the country and very, very young, and it didn’t make a lot of sense, and I felt it might if I came hack and I studied Russian literature and history and a little of the language—which you taught, too.

HZ: It was amazing to me that you were doing all this travelling. You had just come from Eatonton. Travelling to Atlanta was something.

AW: Yes, always trying to put some distance between me and Eatonton.

HZ: You did it! You went to Russia, and at some point you went to France, and another point you went to Africa, and all this while you were a student.

AW: Yes. I was very curious about the world, and I love travel. I’m not so keen on it now, because there’s hardly any place that I really would like to go. Except, now I want to go on the river in the Grand Canyon. That’s the only place I can think of that I really would like to go now.

HZ: Really? It’s just a big drop, isn’t it?

AW: Big drop?

HZ: It’s way down there . . . the Colorado River.

AW: Yeah, that river! But at the time I had never been anywhere—hardly. out of the State of Georgia, and actually most or my relatives had never been outside of this little three-county area in Georgia. It was wonderful to be able to travel, and to just bring back little things, to show them what other people were like in other parts of the world—those dolls that fit into each other . . . things like that . . . shawls that had a lot of embroidery. So it was good. I was always trying to bring the world back to my ramily and to my little town.

HZ: It must have been really astonishing to them. And you were the only one of your many siblings who did that, right?

AW: I had a sister who did it, but she eventually stopped coming back, so I guess I kind of took over that part of it—the one who goes far and says, “Yes, there’s land over there.” And you bring back what you find. I loved doing it. I loved it especially doing it with my mother, to just try and make the world bigger for her.

HZ: You’ve been to Cuba a couple of times, haven’t you? I think I may have told you that I was at Yassar and saw Angela Davis. She had just been to Cuba with you.

AW: Yes, we took five million dollars worth of antibiotics. They can use every bit of that, and it would go to all of the hospitals and all of the clinics. But when we were talking to Fidel later, he sort of pulled on his beard and said, “Well, I think antibiotics are over-prescribed!” So we said. “Well, thanks, Fidel! That makes us feel just dandy!” He was very funny, though. And it’s true—they are overused.

But in Cuba and Nicaragua now and in a lot of other countries, there is a lot of dengue fever, and all these other viruses and things, so they can actually use antibiotics.

HZ: I’m sure they can. The Cuban health system is a wonderful system.

AW: It has been wonderful. lt is not as wonderful now.

HZ: It has suffered lately because of the embargo.

AW: Really terribly.

HZ: People who go to Cuba—like you, Angela Davis, the pastors for peace, and all sorts or people—have been bringing things there. Then they come back, and I think one of the good things about it is they try to call attention to this ridiculous policy that the United States has, of starving the people of Cuba. Of all the dictatorships and tyrannies in the world, this one—Cuba, Fidel—is the one that has to be singled out.

AW: Well, it’s Fidel, I think, it’s his attitude, the man has a real attitude. He’s always had, he’s going to die with it, and they’d better get used to it. He is definitely who he is. And it’s so wonderful to see. I’ve never seen anyone go through so many changes just being himself in a conversation even. That’s lovely.

But the second time I went it was right in the depths of the hard times, and you could actually see that people had lost weight. This was so hard to bear. It was very hard too, to see people trying to get from their houses to work, on foot. This was also before they got a lot of bicycles. But the last time it was much, much better. They’ve been working very hard to improve the transportation and food production. They’re doing something that’s really wonderful— they’re growing more soya beans, and making this incredible soya-bean yoghurt.

HZ: I knew you’d approve or that.

AW: Oh, yes, I do! It’s such a mess—but, because of the embargo there, they can’t have cattle feed. The cattle feed doesn’t come into the country, so the children don’t get the milk that they are promised by the revolution. They were supposed to have milk every day until they are fourteen, and they had to stop having milk at age seven. Now they can use .soya-bean products to bring up this protein.

HZ: This government has a thing, as you say, about Castro. It seems to even go beyond ideology to a kind or fanaticism about Castro. I have a suspicion that, aside from politics, they simply resent the fact that he is so impressive. They figure if you keep seeing him on television being interviewed by Baba Wawa or—that people will compare him to—

AW: Everybody.

HZ: Bush.

AW: Oh, god!

HZ: I’m not giving a one-hundred per cent endorsement to Castro—I want him to know that. But he is a remarkable figure, and I think they don’t like that.

AW: I figure that Fidel’s imperfections are about as big as he is. But still he is formidable. I’m not saying I know anything about his imperfections, I just assume that people do have their flaws, and we have to take that along with whatever else they have. But I often think of what a wonderful thing it would be if Clinton could be person enough to try to learn from him. I think he could learn so much from this person.

HZ: I’m sure Clinton would love to hear that from you.

AW: Well. I’m willing to tell him!

HZ: Clinton is the man who got up at Nixon’s funeral and said that Nixon had struggled all his life for democracy and freedom—

AW: Well, Howie, I didn’t go to that funeral! Some funerals I don’t go to!

HZ: Yeah, well, I don’t like to think about it. You’ve also been to Nicaragua. And I remember shortly after you went to Nicaragua you came to Boston. You stayed with us—which is a real sacrifice—and you were going on a television thing. You spent the night and in the morning somebody came and picked you up to take you to this television thing. And we watched you, naturally, since you were our guest we had to watch you on television. There was an interviewer—you know, one of those who’s not read anything, not only not anything of yours, but not read anything of anybody’s! At one point she asked you where you’d been and you said, “I just came back from Nicaragua.” This sort of startled her, and she said—I think this was the only spontaneous thing which she said—“Why would you go to Nicaragua. After all, Reagan and the Contras were at it at that time, fully, and Nicaragua was the Enemy. And you said, “Cause I love the Sandinistas!” And I thought: That’s Alice! How many people say that on television? People say it secretly, hut not on television.

AW: Well. . . . She didn’t know who they were!

HZ: Probably a new kind of sandal. . . . But that’s what has struck me, and I don’t think I’ve ever said this to you, but what I always really loved about you, Alice, was that, even with all of that stuff—success, Pulitzer, and all of that stuff— even with all of that, you never retreated from your political beliefs, throughout it all. That’s something that you don’t often see, because that retreat is so easy.

AW: But listen, let me tell you something good about you: part of it is that you were my teacher. It meant a lot to have an example of someone who stood by what he believed. You were out there all the time, and this is something that has meant so much to me, my whole life. And I really truly deeply appreciate it.

HZ: We’re going to have to start saying negative things.

AW: Okay.

HZ: Let’s talk about the film. . . . The book.

AW: Let’s talk about the book.

HZ: And the difference between the book and the film. How did you come by the title? I always wonder how people come by titles, because I really have a tough time with them.

AW: The Same River Twice? Everybody’s heard this, but you go to a river and it looks the same, but actually it’s completely different from moment to moment. So it’s impossible to step into the same river twice, even though you think you’re stepping into the same river twice. Then you yourself change. So you’re not the same river ever, either. This is one of the great things about being alive. That’s how you tell you are alive: you’re a different river.

So when I came to work on this book, I was thinking about how this is revisiting something that was very difficult ten years ago, and what did it mean? I was looking for meaning for myself, and a way also to enter a different river with it, and then ultimately to go on into a completely different river altogether.

HZ: I thought you were saying you couldn’t judge the film simply by the book, because it was a different river.

AW: Oh, yes, that too.

HZ: A lot of people made that mistake. The Colour Purple had such an impact on people. Here’s another thing I never told you. I was in Hawaii. I was sitting in the student cafeteria, with a student who was just introduced to me, and she was reading The Colour Purple. Well! I couldn’t let it go unnoticed. I didn’t rush to say: “That was my student.”

AW: Are you sure?

HZ: “That was my student, and I taught her how to write The Colour Purple.” I didn’t say that. I didn’t say it at all. The only thing I said to her was—now think of how restrained this is. I said, “Do you like that book?” She said, “It changed my life.”

AW: Ahhh.

HZ: Really. . . . But what I started to say was that, given the impact or the book, it was a real risk to do a film. So hard to have people satisfied with that film. And you had a hard time being satisfied with it.

AW: I had to accept that it was different. I’ve been thinking about why you decide to collectively do something, rather than stay in your solitude, and for me one of the things that happened was that I was always thinking about how growing up in Eatonton—Eatonton was totally segregated —and the theatre was totally segregated, so white people would be down below and we would be up in the gallery, where the broken seats were—I had never seen a film that had black people in it, in real character roles, where they’re actually real people. They were servants, maids, stereotypes, and caricatures. So I never ever thought that one of my books would become a film, never. It just never occurred to me that that would happen.

So I think that when Steven Spielberg appeared, there was a part or me that really saw it as a kind or magical thing, and it presented a kind of challenge. It was a great risk, of course, because I don’t know if Steven has been south yet. But there was something about just this person appearing. open-hearted, good-hearted, very intense, very loving towards this book. So I don’t think I would have said no. actually, just because of my own circumstances in my childhood and because it seemed to me something that just appeared and that was very positive.

HZ: You were taking a risk. And you say at one point in the book that Steven Spielberg said that his favourite film of all time—you don’t want me to say this!—was Gone with the Wind. I’m sorry!

AW: And that his favourite character was Prissy. Yeah! Maybe he was joking.

HZ: It’s so generous of you to let a guy, whose favourite film was Gone with the Wind, do your book.

AW: Howie, it was not like that. He mentioned this when we were almost at the end of filming.

HZ: Oh, he waited.

AW: He was waiting. . . . I do have this saying that I have made up my own self which is: it’s always worse than you think.

But I think it turned out okay. It’s still not the script that I wrote myself.

HZ: The script you did write is in the book.

AW: Yes, and it mattered to me to have it as a record—I don’t know if you know this, but when you write a script for these people at Warner Bros., or wherever, they actually take the copyright, and they own it. So I actually had to go through a number or small changes to be able to print my own script. I didn’t really know what had happened to it or that people had been reading it, until I was down in L. A. doing a lecture. Some film students came up and they started trying to engage me about my script, which they were being taught in a film class. I realized that my script was actually out there, and that I would really like to have it somewhere where people could see that this is actually my script, and this is how l envisioned a film made about my book.

I think one of the reasons that the film that we have is so far from my script is because of the people down in L.A. and Compton, who were very upset about the lesbianism in my script which they hadn’t seen. So they decided to really go after Steven and Quincy. They made threats and they wrote letters and they had little clubs all over the country and then, of course, on opening night they picketed the movie.

HZ: Your mother wasn’t happy about the lesbianism, was she?

AW: My mother was a Christian—a Jehovah’s Witness—when she died, and before that, a Methodist. She actually had learned from her indoctrination—her religious indoctrination—that this was a bad thing, and that somehow it meant that you were not quite right. She had learned that very same thing about Jews. My mother had never met a Jew in her life. So when she met the man that I was going to marry, she stood there, completely perplexed, trying to figure out, How do I greet this person? I’ve never met a Jew before. Then she remembered where she had seen a Jew before, and it was in the Bible. She took his hand and smiled at him and she said. . . . Can you imagine what she said? She said something very upsetting.

My point is that, here’s a woman who was very open, very loving, and had no way of knowing about hardly anything outside of her community, unless you told her. Which was one of the reasons I was always going off and bringing stuff back. Her religion actually told her how to look at Jews and how to look at lesbians and how to look at the world. And it was a very narrow way of looking at the world.

HZ: Lucky you didn’t have a Jewish lesbian in your book.

AW: The thing is, though, when my mother came to visit me, and she met my lesbian neighbours, she adored them. They were living exactly the way she had lived, when she was in her happiest period in the thirties. To actually meet women who grew their own food, who lived in the house they built themselves, who raised goats, who had animals . . . she was just in heaven! But this time I had to literally bring her from this little town all the way out here, and to share this experience with her in her last days. That period that she was so happy, with me and my lesbian friends, that was the last time that she was actually able to even walk. After that she just declined.

HZ: I remember, in the book, you tell about how, when your family was really in bad straits—maybe they were always in bad straits but this time they were really in bad straits—and they were giving out surplus flour. Do you want to tell about that?

AW: Yeah, but that’s not in this book, Howie. Which book are you talking about? You’re going way back—

HZ: I’m sorry! That’s In Search of Our Mother’s Gardens. Yes, I’m sorry. Well, I love In Search of Our Mother’s Gardens.

AW: I’m glad, I’m really glad! But what was your point?

HZ: What was my point. . . .You think I have a point. . . . Do you remember what you said in there?

AW: Well, this was during the Depression and she was refused flour. In order to feed us, she had to borrow or barter—

HZ: But, wait a minute, I have to remind you about your own story.

AW: That’s because you read it more recently than I have, Howie.

HZ: I guess so. People don’t go back and read their own stuff. They don’t know what they’ve written.

She was refused the flour because she was wearing this nice dress, which the white woman who was giving out the flour resented. The dress had been given to her by your aunt. And this woman handing out the flour thought that this was outrageous, that she was coming here for flour and that she should have this nice dress. It put me in mind of the whole business of welfare, the stories about welfare mothers: My god, look, they have a TV! Or, look! They have this. . . . They’re wearing clothes!

AW: Right, of course. And it’s all envy. My theory is that racism is really envy. I think in my mother’s case this was absolutely true. Here she was, a really good-looking woman, with spirit, and she had gotten these second-hand clothes and she was wearing them. You know that expression: this woman can wear a dress. My mother could wear a dress. So, she was there, she still needed the flour, and this woman had this attitude that, “If you’re gonna look better than me, I’m not gonna give you anything.”

I was listening to your People’s History of the United States on the way down to San Francisco, and I can see that that is part of what has been happening—this envy of what native people have and of what people of colour have. It’s very, very clear that racism in a way is a mask for this desire to have what other people have.

HZ: I never thought of it as envy, but I guess it’s connected with that, in that these are people who don’t have much, and people who don’t have much are vulnerable to prejudice and racism. It suggests that very fundamental to getting rid of racism—maybe nothing is sufficient—but one of the crucial things is dealing with the general impoverishment of all working people, like blacks, Latinos, and so on. It’s deprivation that leads them to fight one another, all to the benefit of that top one percent.

AW: Right. The ruling class. Is that accurate? I’m trying to find a phrase for that one percent. A word. A name. So that we don’t have to always get into colour, or whatever, but something that is really accurate.

HZ: I use the word “they.”

AW: They? No, Howie, I’m trying to get away from they!

HZ: They have done this to us. They control the media. They run—

AW: I know, I know. l know, but it seems to me we need a word, we need a phrase, we need—

HZ: Ruling class is two words.

There are some questions from the audience I’m going to repeat the questions that are posed, Alice. . . . The first question is about your response to the attacks that were made on you as a result of The Colour Purple, and the treatment of black males in The Colour Purple, which became an occasion for attack, and then he wants you to also connect this with the Million Man March and Waiting to Exhale.

AW: l felt thoroughly trashed, actually, for many years, because the attacks didn’t just happen around the showing of the film. They continued for a long time. As I talk about in this hook, The Same River Twice, unfortunately at the time I had Lyme disease, and I was reeling from this internal struggle. The only way I could keep going was to just stay in my own work. I did a lot of work. But all along I felt that, if I did recover myself—also my mother was dying; she’d had a stroke, and this was another very difficult thing—I knew that I would eventually gather something complete with which to explore, not just what I was doing in making the film of the book, but also there are all kinds of choices and positions and I could use this to answer—and also to help us, collectively. as black people—to deal with the fact that we really must not try to kill off our artists. We must give them respect, we must give them freedom, and we must learn to treat them with a great deal more gentleness than we do.

Black men—and this is not all black men by any means— the ones who were very violently opposed to my work, I think were dealing out of ego, and were unable to even see the male characters that I had created. Also, because I think in this country black men have taken their model for manhood from white men and European white men, they have a whole notion of how things are supposed to he if you’re a man. If you then create a male character who’s not like that, or a male character who changes from that to something else, something more gentle, more open, then this male character, this black person, this man cannot even be seen by men who don’t recognize that as being male.

I enjoyed the Million Man March. I had my television fixed just so l could watch it. And I spent the entire day in my pyjamas watching it. I didn’t feel left out as a black woman, I felt that black men must get together, that they really must embrace each other and be gentle and loving with each other. Until that can happen, I don’t think they can be gentle and loving with me. And I want that, I would like that to happen.

Waiting to Exhale. I enjoyed it. I went to the movie with my brother, who flew out to spend the holiday with me, my brother and my sister-in-law and friends. I guess what’s puzzling to me is that I find those women very strange. In my personal life I don’t think I know any women who are that desperate for men. But I have inquired among people I meet, and they say that this is true. I feel like the world is full of abundance in relationships as well as in other areas and that to be so fixated on any person or thing is just not good for your soul. But on the level of whether or not Terry MacMillan should have written this or made a movie or whatever, of course she should have. This is her reality; this is how she sees life. She is an artist and she should be supported in her view. I don’t know what’s going on with the movie or with her, but I hope that people are more understanding and less eager to trash than they were ten years ago.

HZ: Maybe there’s an important difference, between criticizing as part of a good discussion that is initiated by a provocative film or hook, and attacking. It would have been perfectly okay, I think, for people to discuss the things you raised in The Colour Purple, discuss the question of black males and their relationship with women. That’s one thing. I think the same thing with Terry MacMillan, to discuss this question of women and what their lives are like. Another question. . . . Salman Rushdie went to Nicaragua, appreciated the revolution, liked the Sandinistas, but thought that his job as a writer should be that he’s always in opposition to the State. Do you feel that way?

AW: I definitely feel like it. As I said. I was born in opposition to this State, to this United States. But when I was in Nicaragua—which is so poor, such a materially poor country—it was so amazing to me, unbelievable to me that this big fat bully of a country here would actually grind those people into the dust, just for fun. l found I really liked the people who were the government men. But they were the revolutionaries who had become the government.

There was a woman, Donna Maria, for instance, who had taken a city. In the battle, they took city after city, city by city, and this woman had taken a city. She was like Jeanne of Arc, she was really formidable. And of course I loved her. What was her role? What was she trying to do? She was trying to provide health care for everybody in Nicaragua. That was what she was doing.

There was this poet—his first name is Thomas, I can’t remember his last name—they had imprisoned this man, they killed his wife, they’d done all these awful things—this was before the Sandinistas took power—and when l was there, he was the one going around trying to be sure—since they had to have prisons, all the prisons had to have certain books, they had to have cultural events (some of you may know who I’m talking about) the thing that I loved about him was that he said—talking about the people who had been so awful before the revolution—“Yes, we will take our revenge on you. And you know what our revenge will be? Our revenge will be to teach your children to read!” So I liked them.

I have a feeling I would not be all that comfortable under any government that felt like a government. But that has more to do with me, I think.

HZ: Another question. . . . How does one keep going, especially in the corporate world? How do you keep your self-esteem?

AW: I don’t have a lot of experience with the corporate world. . . . You just keep going. You just keep on, keep on keeping on. You just keep going. Also, in my case, I meditate, which helps a lot—just on a practical level. I’m very much interested in all kinds of things for the mind and the spirit and the soul. And I seek those things out. I am not one to starve myself spiritually. I think it is from that well in the self that your self-esteem grows. If there are ways in which you can take care of yourself, if you can take care of the inner you, then do that, whatever it is. If you’re quiet enough, no one will have to tell you what those ways are, you will tell yourself.

HZ: In terms of teaching literature, do you have some thoughts about how to structure or restructure the canon?

AW: Dismantling. No, I don’t really. Maybe you can tell me: What good is the canon? What is the canon? If there’s a canon like that, who would want to be in it? I’m so happy not to be mixed up in that.

HZ: I remember someone, one of them, got excited because somebody had put on their reading list, I, Rigoberta Menchu, which those of you who haven’t read should read. It’s a remarkable piece of literature—the autobiography of a servant girl. It’s maybe the Guatemalan equivalent—not quite—of The Autobiography of Malcolm X. Only in its impact. My god! Imagine putting the autobiography of Rigoberta Menchu on this list. We might have to take off Thomas Hardy, to make room.

AW: Don’t take off Thomas Hardy. Choose somebody else, like T. S. Eliot!

HZ: We can argue about who we should take off.

AW: Yes, that’s what we should do! We should pick out who we want to take off.

HZ: It would be fun. Let’s really give them heart attacks.

AW: Yes, two can play this game. But then Rigoberta Menchu went on to win the Nobel Prize.

HZ: The questioner wonders what you think about the women’s movement, the direction it’s taking, and feminist studies.

AW: You would think I would know this, right? But I actually don’t. In my life I just seem to be always working with women, working for women, trying—But I never, really feel like I know anything except that I’m actually doing work. It’s very hard to explain. But I couldn’t begin to answer you, really.

HZ: You go into bookstores now and there are shelves and shelves of books on history of women. It’s been amazing.

AW: It is. It’s wonderful.

HZ: So, I don’t think there’s any reason to be discouraged. Okay. The next question is about genital mutilation, and is anything being done to stop that in some countries?

AW: Yes, actually. In Sierra Leone, they have started—What is really helpful is that Amnesty International has taken it on as a human-rights violation. The United Nations has also decided it is a human-rights violation and as you know it was brought before the Fourth Women’s Conference in Beijing. So the world is quite aware of this issue. What that means is that in countries like Sierra Leone, for sure, and Ghana, Amnesty International has, in conjunction with local people, set up week and two-week long learning sessions. People are trying. It’s very slow because it’s so ingrained. It’s

like that thing about whether the glass is half empty or half full. On the one hand, I’m so happy that Amnesty has taken this on, because it means a lot. This is a big organization and the UN is a big organization—they can reach people. But at the same time Amnesty has said that even if we take this on with every ounce of our energy and all of the funding that we could possibly raise and all of the everything that you could possibly get together to fight it, we couldn’t get to the end of it for thirty years. I’m happy that we’re moving, but when you think about how long it’s going to be. . . . Sometimes when I think about the way it is happening every minute, it’s very hard to just sit still. You want to fly apart. But that’s the reality of the situation.

HZ: The next question is about the genocide of people of colour in this country, and when will Amnesty International recognize what’s happening here.

AW: My answer is: when you make them notice it. It took so many years of really pressing them before they could see that genital mutilation of little girls is a crime against these girls. It’s not as if this is something that just happened, that they were willing to see this. This is where your activism comes in, this is where you have a role to play. You can force these things. I hate to say force, but you can make changes by your own behaviour. This is basically what has happened with female genital mutilation, and it’s been a lot of work. But if you decided that you cannot bear this genocide in black communities, a day longer, you will be very motivated then, to get the world to hear you on this issue, and that’s what I would say to do. I think each of us can do the work that we feel most strongly about, and no one of us can do all of it.

HZ: The question is about sexual violence in the black community. As an African-American working in the black community, how do you address the problem of sexual violence in this community, given the same kind of problems that arise when you wrote The Colour Purple. You dealt with that, and you were attacked for dealing with it, for pointing to it, because it’s embarrassing, so how do you deal with it?

AW: I think, if you feel this very deeply, you have no choice but to address it. You have no choice but to risk that you will be attacked, and you should draw comfort from your friends, if you have friends who care about you, and if you have a community. I think it would help all of us during this time to try to strengthen our friendships in our communities, and to really try to be present for each other. I think that this period that we’re in and that we’re going to keep going through might be the roughest of all the periods that those of us who are living in this age will experience. It’s really necessary to try to connect with people one on one, but I would say never yourself give up on the idea and the motivation of making a stand and speaking out. It’s our only hope.

People act like they think that if we’re just quiet somehow this evil that has beset us will fall away. Well, that’s not happening. It’s getting more dense and it’s taking our children at a younger and younger age.

I often think about what it would have been like, if O. J. Simpson had read The Colour Purple and if he had been encouraged to read the book, to see the film as art that could help him deal with his life. What would that have meant? I think it might have meant that we, as a black community, could have been saved a lot of embarrassment, a lot of horror, a lot of grief, because he would have been a different person. So I think we have to call on and rely on every thing, every resource.

Look at literature. Women are speaking out, and black people—men too—now are speaking out. It’s not as if this is unbroken territory, all new. In fiction and non-fiction, we’ve been dealing with this now for a very long time. Even if people are in denial, the fact still is that we pretty much know that our communities are being torn apart by violence and by sexual violence, by battering, by drugs, by all of those things.

HZ: We only have time for one more question. Okay! Alice, you talk about speaking out against abuse, but in your book, The Colour Purple, Sophia was punished for speaking out, and Celie was rewarded for taking her abuse.

AW: Yes. In the book she was rewarded. Oh, darling! It’s been such a wonderful evening. I think there is no answer, really, for your question. I would say you’d have to read the book again, and also think about what does happen to assertive women in this culture. Try to imagine what it was like, at the turn of the century, for a black woman, who would hit a white man in the middle of the apartheid south. Celie I would not say was rewarded for being abused. Abuse is not a reward. Abuse is very painful. I think this is a situation where you would have to re-read the book, and try to separate me, here on this stage, a little bit from these women who were alive during my grandparents’ age.

Howard Zinn is the author of A Peoples’ History of the United States and You Can’t Be Neutral on a Moving Train.