Thomas Lovell Beddoes was born in Clifton, Shropshire, in 1803, to a distinguished and eccentric family. His mother was a sister of the novelist Maria Edgeworth; his father, often referred to in his time as “the celebrated Dr. Beddoes,” was a colleague of Sir Humphry Davy, who lived with the Beddoes family and taught at the Pneumatic Institution in Clifton, where Dr. Beddoes administered laughing gas to Coleridge. The doctor also tried his hand at poetry; his long poem “Alexander’s Expedition down the Hydaspes and the Indus to the Indian Ocean” has been called “one of the strangest books in English.”

As a student at Charterhouse School, Beddoes wrote prose narratives of which only Scaroni survives, and probably began there his long poem “in three fyttes,” The Improvisatore, which he would publish with other juvenilia in 1821 as a pamphlet while still an undergraduate at Oxford. These early works promise little for the future except their ghoulish atmosphere, which was to remain a constant. His next volume, the only other one published during his lifetime, was The Brides’ Tragedy, which appeared the following year and was a critical success. In 1825 Beddoes left England to study medicine in Gottingen where he eventually received his MD. He would spend most of the remainder of his life on the continent, frequently in trouble with the authorities for drunken and disorderly behaviour and for his involvement in radical political movements. He lived for a year with a Russian Jewish student named Bemhard Reich, who may be the “loved, longlost boy” of “Dream Pedlary.” During his last years, his companion was a young baker named Konrad Degen, who later became an actor of note. A pleasant stay of seven years in Zurich ended with Beddoes’ expulsion on political grounds. In June 1848 he left Degen behind in Frankfurt and returned to Switzerland, where he put up at the Cigogne Hotel in Basle; the next morning he cut open an artery in his leg with a razor, gangrene set in, and the leg was amputated below the knee. Finally, on 26 January 1849, he succeeded in taking his life with poison, having written the same day to his executor, Revell Phillips, “I am food for what I am good for — worms.”

Beddoes has often been called a “poet of fragments,” most of which are embedded in unfinished Jacobean-style tragedies. Their dramatic structure has the form of quicksand, in which dazzling shreds of poetry sink or swim. His magnum opus was to have been Death’s Jest Book, a kind of bottomless pit that absorbed most of his creative energies during his final years. As in all his plays, the plot is murky to the point of incomprehensibility, and the characters exist mainly to mouth Beddoes’ extraordinary lines, though they do collide messily with one another. One critic has observed that they have “the essential unity of dream characters” who meet “in the dreamer” and are merely “emanations of the central idea.” All this does result in a bizarre kind of theatricality, and it might be interesting to try to sit through a staged version of Death’s Jest Book. Unlikelier closet dreams have made it to the boards.

Death was Beddoes’ main subject, both as a poet and as a medical man; he seems relaxed and happy only when writing about it. Pound (in the Pisan Cantos) mentions “Mr Beddoes/(T.L.) prince of morticians … centuries hoarded/to pull up a mass of algae/ (and pearls).” Any anthologist is bound to include a bit of the former (the creepy “Oviparous Tailor,” for instance) as well as some of the latter, and none can avoid “Dream Pedlary”: his most anthologized poem, it is also one of the most seamlessly beautiful lyrics in the English language.

Pound evokes “the odour of eucalyptus or sea wrack” in Beddoes; one could add those of rose, sulphur, and sandalwood to this unlikely but addictive bouquet. Edmund Gosse, whose landmark edition of Beddoes’ work appeared in 1890, got it almost right in his preface:

At the feast of the muses he appears bearing little except one small savoury dish, some cold preparation, we may say, of olives and anchovies, the strangeness of which has to make up for its lack of importance. Not every palate enjoys this hors d’oeuvre, and when that is the case, Beddoes retires; he has nothing else to give. He appeals to a few literary epicures, who, however, would deplore the absence of this oddly flavoured dish as much as that of any more important pièce de résistance.

One should qualify that by adding, in the century since it was written, the little band has swollen to something like a hungry horde, avid for what Pater called “something that exists in this world in no satisfying measure, or not at all.”

from Death’s Jest Book

Siegfried: How? do you rhyme too?

Isbrand: Sometimes, in leizure moments

And a romantic humour; this I made

One night a-strewing poison for the rats

In the kitchen comer.

Duke: And what’s your tune?

Isbrand: What is the night-bird’s tune, wherewith she startles

The bee out of his dream and the true lover,

And both in the still moonshine tum and kiss

The flowery bosoms where they rest, and murmuring

Sleep smiling and more happily again?

What is the lobster’s tune when he is boiled?

I hate your ballads that are made to come

Round like a squirrel’s cage, and round again.

We nightingales sing boldly from our hearts:

So listen to us.

— Thomas Lovell Beddoes

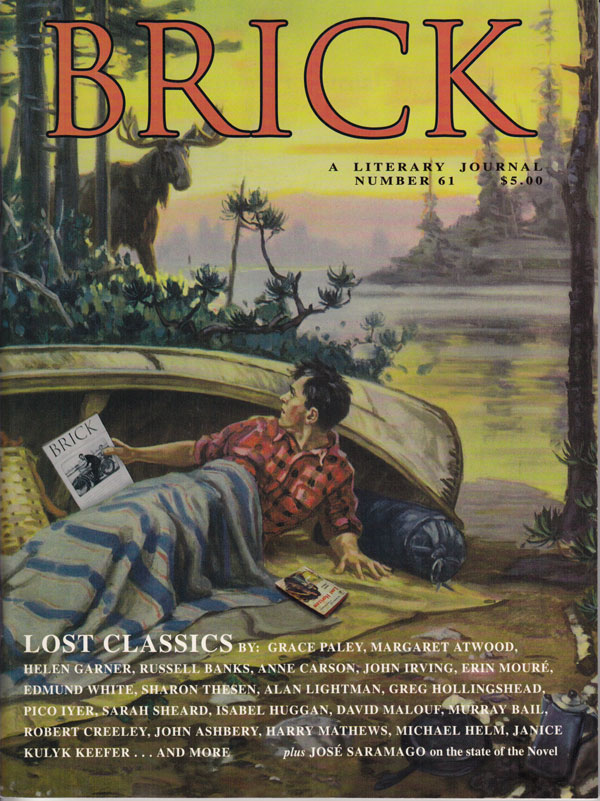

John Ashbery (1927-2017) only appeared in Brick once, in 1998’s Brick 61, an issue dedicated to uncovering lost classics. He is recognized as one of the greatest American poets of the twentieth century.