“P. S. I had my picture taken by a Mr. Breitenbach Tuesday.”

Reading through One Art, a selection of Elizabeth Bishop’s letters claimed by its editor, Robert Giroux, to be tantamount to the poet’s autobiography, I came upon this sentence early on in the unfolding of a profuse correspondence. The passage is affixed to the end of a letter dated June 6, 1945, to Bishop’s friend and mentor Marianne Moore, who had been unwell. While their decade-long association had engendered in Bishop what critic David Kalstone called a “burden of apology and gratitude,” she instinctively wrote Moore the kind of intelligently chatty dispatch intended to provide both pleasure and comfort, or at least as much as the stoic older writer was willing to accept from the younger one. And so, generously, Bishop wrote often to Moore, even in the years they lived quite close to each other in New York City. “Oh, and here’s something else that might amuse you” is the subtext of the postscript about the photographer; having already signed her name, Bishop seizes the impulse to offer one more tidbit, hoping to prolong any restorative impact.

Bishop fattened the envelope by inserting a telegram plus another letter she had just received from Ferris Greenslet, the general manager of Houghton Mifflin Co. The week before, Greenslet had accepted Bishop’s first book of poems, North & South, for publication, and his telegram announced that she was to be the recipient of the first annual Houghton Mifflin Literary Fellowship in Poetry, a one-thousand-dollar award. Her manuscript had been chosen from a pool of 833 submissions. Bishop sent these glad tidings to Brooklyn as balm for an ailing friend whose continued support had undoubtedly helped shepherd the work into print.

Ten years earlier, fast upon her graduation from Vassar, with similar advocacy on Moore’s part, a small group of Bishop’s poems had been published in an anthology of new poets. But a fledgling poet of twenty-four is a different creature than a struggling writer of thirty-four. Along with a welcome infusion of cash, the literary prize brought reassurance, and the anticipation of a volume all of her own must have afforded Bishop as much relief and satisfaction as she would allow herself to feel, given her tendency toward self-sabotage. On June 3, she wrote to Greenslet about her willingness to play an active part in the shaping of what he had called “the physical embodiment” of her book, to consider fonts, bindings, and paper stock and to confer with him on the order of the poems. And, no doubt in response to a request from him for publicity materials, she added, “I haven’t any photograph of myself on hand, but have already made arrangements to have one taken.” Thanks to these dated letters—one to Greenslet declaring she had an appointment to have her picture taken and another to Moore three days later announcing that it had been done—it can be established that on June 5, 1945, she posed for her portrait.

Enter the photographer, listed rather formally in the index of One Art under “Breitenbach, Mr.” She described him to Moore: “He is a German refugee. He wanted to see the poems first. . . . He is very SERIOUS.” In general, Bishop was ambivalent, if not averse, to the idea of having her picture taken, but hiring a photographer who took an active interest in learning about his client’s creative ventures boded well. Bishop needed to have a professional picture of herself for publicity purposes surrounding her award. She was in search of an official portrait, not a casual snapshot; this was business. Perhaps the photographer had been recommended to her by the philosopher John Dewey, a Key West friend who was one of her “sponsors” for the Houghton Mifflin prize, and also the subject of a Breitenbach portrait.

The name Joe (Josef, Joseph) Breitenbach is one I have heard for many years. His images of hardscrabble life in Korea and Japan, and a few provocative female nudes, line the walls of the New York apartment of another German refugee who was a friend of both Breitenbach and my parents, so I knew a bit of his story. In 1933, the Bavarian-born, self-taught artist fled from Munich, where he had operated a successful photography studio, pursued by the Nazis as much for his political activism as for his religion. He went to Paris and set himself up again as a portrait photographer, producing a series of studies of fellow refugee and exile artists including Bertolt Brecht, James Joyce, and Max Ernst. Rounded up by the French and interned when war with Germany was declared, Breitenbach eventually managed to escape and make his way to New York in 1941, just a few years before Elizabeth Bishop crossed paths with him. For decades he taught photography at The New School and at Cooper Union. He died in 1984, aged eighty-eight.

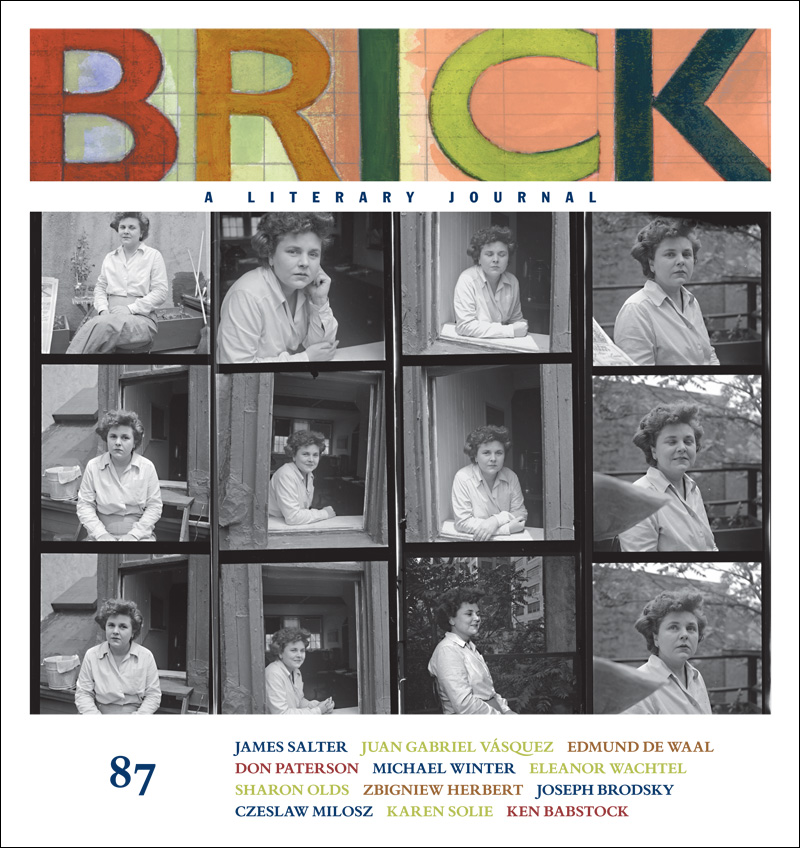

Breitenbach’s arresting portrait of Brecht, his fierce black eyes unyielding, haunted me from the moment I saw it in a portfolio in my friend’s collection, and it surfaced again in my mind’s eye as I read Bishop’s note to Moore. I wondered what kind of image he might have captured of Elizabeth Bishop. What had become of the pictures from this sitting? I had to find them. Through my family friend, I made contact with the director of a photography gallery, who in turn led me to the executor of Breitenbach’s estate, who gave his permission for me to have access to the photographer’s archive currently preserved at the Center for Creative Photography at the University of Arizona in Tucson. Bishop’s fastidious habit of dating letters facilitated the curator’s search there, and she was able to locate three contact sheets that, to the best of her knowledge, had never been printed.

And suddenly here she is. Three strips of film, shot on two separate occasions. One session produced nothing terribly successful. The portraits feel strained, the sitter looks either slightly irritated or befuddled. Bishop is wearing a tailored blouse and skirt of tightly woven houndstooth material, set off by wide, starched, white cuffs and pointed collar flaps. Her lush, unruly wavy hair has been relatively tamed and she is sporting small earrings and a manicure. Breitenbach has posed Bishop on a low stool before a squarish, marble-topped table, upon which a photo album of her Nova Scotia family sits open. Her small hands engage with it only tentatively. The placement of the camera has most likely been dictated by a large bookshelf at the rear of the space, with its murmur of “Author, author.” The photos have a forced “How shall we do this?” unresolvedness to them; in two frames, Bishop is shown holding a lit cigarette in what could be an attempt to deflate the tense formality of the situation.

There follows a change of concept: a series of sixteen tightly manipulated studio studies that on first viewing seem unworthy of the photographer of the Brecht portrait, “mug shots” taken from the waist up against a swath of medium-valued seamless paper. One could easily mistake these for passport photos. Bishop’s character eludes Breitenbach’s eye, she won’t let him in, her innate defensiveness projects a nearly impenetrable barrier. These stiff, strained compositions are dominated by Bishop’s aura of steely diffidence. She is both skeptical and phlegmatic. Tempted to dismiss the images for their lack of spark and connection, it seems this very lack is somehow crucial to an understanding of Bishop’s persona. Having returned to New York after years in Key West to gain some distance from an imploding love relationship, hobbled by severe asthma, unable to write, she had recently hurled herself into a binge of drinking to get through “this dreadful time.” Something within Bishop fiercely refuses to meet Breitenbach halfway, the minimal requirement for a successful portrait, and the photographer is reduced to documenting her wilful withholding. Certainly these images reveal a truth, heartbreaking.

Another session on another day yields a more appealing glimpse of Bishop. She is more at ease, her face more relaxed, softer, her body language less rigid. Perhaps she finds Breitenbach less SERIOUS. The gold hoops in Bishop’s ears and the polished nails remain, but the uptown clothing is gone (“Thank heavens!” we can almost hear her exclaim), replaced by a comfortable wrinkled shirt and khaki trousers. The setting this time is her tiny Greenwich Village apartment on King Street (“I have often wondered where the ‘King’ in King Street came from—it certainly isn’t very kingly now . . . ”), a garret whose diminutive scale is considerably enlarged by a small outdoor deck accessed through a rough-hewn window passage. A rustic stepladder pushed up under the low sill allows for clambering in and out; the careful negotiation between interior and exterior spaces strikes a perfect, Bishop-like chord. The deck is strewn with the rudimentary trappings of urban gardening: planter boxes displaying signs of early growth, some potted specimens, a garden shovel. While the bounty of her Key West garden is a distant memory, some of these plants come from seeds she brought up with her from Florida. Above a simple terrace railing, the tops of some honey-locust trees weave a lacy screen that helps soften the looming presence of tall buildings nearby. Breitenbach’s six exposures of Bishop seated just inside her open window looking out at the photographer (and, by extension, at us) are by far the most affecting images of all. Here, artist and model have finally found a sympathetic relation to each other, with Bishop’s cherubic face liminally framed and engaged. In words Robert Lowell used to describe a prevailing sensibility in North & South, Bishop appears “weary but persisting,” but at last she grants limited access to her expansive spirit and the depths beyond.

Eric Karpeles works as a painter and also as a writer on the intersection of visual imagery and language. He is the author of Paintings in Proust and translator, from the Italian original, of Proust’s Overcoat.