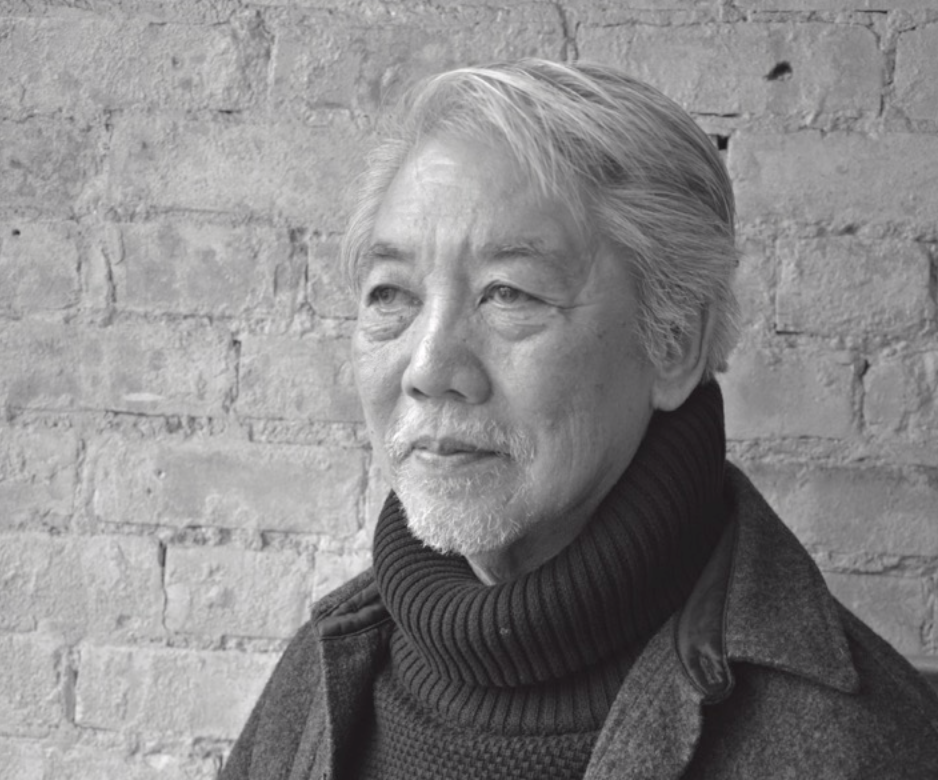

Having lived for almost seven decades, death is not new to me. Each time someone I love dies, I am struck not just with overwhelming grief, but with the finality. The power of that finality staggers me every time. And so it is with Wayson Choy. I find myself still coming to terms with the fact that I will never see him again. I will never hear his voice, share a joke, exchange an email, talk about books. I will never walk down a city street with my arm through his.

On the day Wayson died, my husband, Michael, and I were staying with our daughter and her family in their Toronto home. It had been an unusually cool and rainy spring, so when we noticed that the sun was shining, Michael and I decided to go for a morning walk before beginning preparations for Wayson’s belated eightieth-birthday celebration. We left our daughter in the kitchen mixing a cake batter for the special occasion. She had spent the previous day looking at various recipes, and after much consideration had settled on vanilla chiffon. There would be chocolate and vanilla ice cream as well. But of course, our party never happened. While Michael and I were walking in Trinity Bellwoods Park, the cellphone rang. It was Marie, of Karl and Marie Schweishelm, the couple Wayson had been sharing a home with for more than thirty years. She told me Wayson had died earlier that morning. It had all happened so quickly. They were still in a state of shock.

That evening, in a tailspin, we set the table and served one of Wayson’s favourite meals: prime rib and roasted potatoes with rich brown gravy, light on green vegetables. We sliced the cake my daughter had baked. Nine devastated people sat around the dinner table and talked about Wayson. We couldn’t say enough.

We talked about how much we loved his work and his ability with language. I remembered the excitement I felt when I read an early draft of The Jade Peony. As I turned the pages and entered the world of those three Chinese children living in Vancouver during the Second World War, I knew that his book was going to be important. The story of those children spoke directly to me. Wayson had written about things I had experienced: Sek-Lung’s confusion over kinship titles mirrored my own; he was admonished and told he was a mo no or no brain, while I was called a mo yung or no use; and his joy at receiving a lucky red money envelope was something I too had felt. With The Jade Peony, Canada’s literary landscape was about to change.

Not long after the publication of The Jade Peony, Wayson found out he was adopted. It was a revelation that I expected would be unsettling, but when I had asked if he was upset, he told me no. He felt he had so much to be thankful for, that he had been lucky all his life. The son of Lilly and Toy Choy spent his childhood in Vancouver’s Chinatown and his teen years in Belleville, Ontario, and if his parents had kept a secret from him, they did it out of love. He reminded me, “Family is who loves you.” And indeed he was a much-loved man.

More than his writing, we talked about Wayson the man: his kindness, generosity, humour, wit, and wisdom. We talked about the family events made more special by his presence: dinners, barbecues, weddings, births, naming ceremonies. There were funny stories, often about Wayson’s delight in playfully navigating his way through life. I remember, soon after my daughter gave birth to her first child, standing in her hospital room and looking out the window onto University Avenue. The Santa Claus Parade was in progress, and I was sure Wayson would not make it through the crowds of exuberant children, the marching bands and floats. But as if by magic, he appeared bearing gifts. Stuck on the other side of the road, he had approached a police officer and told her he needed to get to the hospital to visit his new granddaughter. The officer gallantly took Wayson by the arm, guided him past the marchers, and deposited him on the other side of the road. I can still see the expression on his face: serene but also pleased with himself, confident that charm is more effective than force.

My son-in-law Morgan talked about how his friendship with Wayson deepened during a trip to Parry Sound when Wayson hired him to drive him to a literary event. He also told us he had spontaneously decided to show up at Wayson’s door two nights before he died, and the two of them dined at the Pearl Court, where Wayson was a regular. They talked that evening about everything and solved the world’s problems. At midnight, the manager asked them to leave because the waiter wanted to go home.

Wayson had a quality that made the young adults in my family gravitate toward him. In addition to being a great listener, he seemed to always have the right response. It came down to his kindness: he treated the people both in his books and in his life with respect and generosity, allowing their humanity to be revealed and acknowledged. He never shied away from difficult topics, from the dark side of life.

We shared other stories. Whenever we went to a restaurant, he would predictably ask the server which main course had the largest serving of meat. He did not care about vegetables. He could eat a steak the size of the sole of his shoe.

Wayson was my dream dinner guest. If the meal I served was good, he was effusive with his praise. If the meal left him indifferent, he ate it regardless. Once, I watched him eat one of my sister-in-law’s rice tamales; he was in a state of rapture, savouring each mouthful. When he was in the hospital after his first major asthma attack, Michael made him various medicinal Chinese soups using my mother’s recipes. Each time I delivered one of these soups, I was astonished at how Wayson would devour the offering like a starving man. When he finished, he would put his spoon down and tell me he hadn’t had soup like that since his mother made it. Then he would tell me how lucky I was to have married Michael. I suspect what he really meant was how lucky for him!

In 1995 with the publication of The Jade Peony, Wayson became one of Canada’s literary luminaries. For many years the Chinese community had existed in the shadows of Canadian society, and he had opened a window onto a world little-known to Canadian letters. This book was a major step forward in terms of recognizing the Chinese and their role in Canada’s history. It was on the Globe and Mail bestsellers list for half a year. His readings were packed, and when he spoke, his audiences were enthralled. A fellow writer once asked me how Wayson did it. Maybe those decades of teaching and speaking in front of classes—first with the Durham District School Board and then at Humber College—had honed in him the capacity to read a crowd and connect with them. It was a talent, something intangible, a gift from the gods.

At that time what he gave to an aspiring writer like me was hope. I had grown up in Canada during the midfifties and early sixties. The books of my youth were written by white people, and it seemed there was no place for stories from people who looked like me. Wayson was part of a pioneering group of Chinese Canadian writers including Paul Yee, SKY Lee, Fred Wah, and Denise Chong, writers who were proud to tell stories rooted in the Chinese Canadian experience and who were weaving them into Canada’s larger narrative. Simply seeing these stories in print gave me confidence to pursue my own work. And Wayson paved the way for so many others: Kim Fu, Kevin Chong, Jen Sookfong Lee, Carrianne Leung, Lindsay Wong, JJ Lee, and Madeleine Thien, to name a few.

A reviewer once stated that Wayson wrote “like an angel,” but his exquisite writing was also unflinchingly honest. His characters were complex creatures and not always likeable. And it must not have been easy to write about being gay during the 1990s. Homosexuality was still not widely accepted in the Chinese community. It was something best left unspoken. As it turned out, Wayson was a trailblazer.

I met Wayson in 1994 at a fundraiser for Cahoots Theatre, where he was an artistic director. I had admired his short story in Many-Mouthed Birds: Contemporary Writing by Chinese Canadians, and he agreed to read a portion from an early draft of my first book, China Dog and Other Stories, but I wasn’t sure I would ever hear from him.

He responded. It was clear Wayson understood how vulnerable I felt. I was well into middle age and unpublished. Thankfully his feedback was encouraging and insightful. In his gentle way, he challenged me to do better. He believed that the written sentence should be clean, with nothing superfluous allowed. I can still hear him pointing to a sentence and saying, “Too many rhinestones.” He would highlight scenes that worked, ones that furthered the story and created resonance. He asked questions that made me dig deeper into the text and my characters. He told me to never back away from what was uncomfortable. As far as he was concerned, secrets were meant to be uncovered. The truth was all important. Even though characters might be dishonest, the writing could not be. And in this quest, his mantra, “Never surrender,” was repeated to me time and again. He was a natural teacher.

Wayson and I became instant friends, and soon he was a regular at our home in High Park. He used to muse about whether we had been brother and sister in our past lives. I have often thought about why Wayson was such an important friend for me. I was raised in a small town in southern Ontario where for several years I was the only non-white child. My teachers, the shopkeepers, the firefighters, the police officers, and the doctors were all white. Even the people who wrote my favourite stories were white. The only non-white people in the town were my parents and I and the family who operated the local Chinese restaurant, a father and his two adult sons. As a child I tried hard to fit in, and for the most part I succeeded. But in the process, I lost something. My parents represented a world I understood but did not belong to, and I knew that I would never be a part of the white world that existed around me either, at least not then. And yet I saw the world through a Western lens.

As strange as it may seem, Wayson was my first real Chinese friend. I knew other Chinese people in the city, but to base a friendship solely on race felt forced. Although I lived in Toronto at the time, I was not a member of the Chinese community. With Wayson, there was an immediate bond, partly because we were both writers and we were both Chinese; this gave our connection further depth and meaning. Here was someone I could talk to about my family background without having to be embarrassed or selective about details. He understood the clash of cultures, the stress of immigrant lives, and the position of being caught between two worlds. There was no need to explain. We could share jokes that were based on our mutual understanding of Chinese peasant immigrant culture. But there was more. Wayson faced life’s difficulties with resolve and quiet strength. A mutual friend told me Wayson had once said to her, “When times are good, be careful; when times are bad, be patient.” They were words that stayed with her and that I believe guided Wayson as well. When he wrote a foreword for my first book, China Dog and Other Stories, he wrote about being “the other”: how that status had suppressed writing from the Chinese Canadian community and how we had unwittingly cooperated. We were both outsiders; in our later years, we began to understand that our stories were worth telling. When I was with Wayson, I could express and explore any thought without being ambushed or diminished. I felt safe.

Not long before Wayson died, I told him about a phone call from my older half-brother, whom I had not spoken to for over a year. He was calling to inform me that he had sold his house and had moved into a condo. He then went on to tell me that Michael and I were too old to be living outside the city, that we needed to sell the farm and do what he had done. I listened politely and thanked him for his concern. But when I hung up, I shouted at the phone: “How dare you tell me how to run my life! For Chrissakes, I’m collecting an old-age pension!” When I recounted this conversation to my other friends, they laughed and sympathized with me. But Wayson? With a deadpan expression but eyes twinkling, he said, “He’s your older brother. He has every right to tell you how to live your life. You’re a know-nothing little sister. If you were smart you would have asked him to look for a unit for you in his building.” And we both laughed. He understood the cultural tensions in that conversation. And he was right. I should have asked my brother to look for a condo for me in his building. This of course would have allowed him to inform me that his building is so popular that units are rarely available and he was lucky to find one.

On the day Wayson died, we talked and talked about him. As a writer I had lost a mentor and one of my best readers. But as a family we had lost a dear and close friend. We talked about how he was a lifelong bachelor and a committed family man. He belonged to several families. We had adopted him more than twenty years ago. But there were three families who formed the foundation to Wayson’s life. In Toronto he lived for more than thirty years with Karl and Marie and their daughter Kate. His rural family, the Noseworthys, lived outside of Caledon. And in Vancouver, where he visited with friends and relatives, he had a home with the Zilbers. I talked about his wide circle of friends and how it seemed to me that no matter where I went with him, we were bound to run into someone who knew him and was pleased to see him. Most of all, as we sat around the table that night and shared our grief, we talked about how much we loved him and how much better our lives were because of him. We felt blessed that Wayson had been a part of our family. Because family is who loves you.

Judy Fong Bates came to Canada from China as a young child. She lives outside of Toronto with her husband on a farm where she is an avid gardener. The Year of Finding Memory, a family memoir, is her latest work.