In the blazing hot early June sun, fresh off a transatlantic flight, I bicycled across town to the Gardiner Museum for the second-last day of Yoko Ono’s The Riverbed exhibition. I rode through a gauze of hazy bliss that might be equally described as early summer smog or jet lag. Not yet on high-alert frequency, I almost got hit by another cyclist on the way there. After locking my bike, I juddered into the gallery. Slowly, I climbed the stairs, entered the cool white room, and immediately saw a seventy-something New Ager sitting cross-legged on a filthy black pillow on the floor. There was a goateed man in tearaway pants, wearing a camp-counsellor necklace, cupping a rock as if weighing it in his hands. I made my judgments.

Like most people, I came to Yoko Ono with some baggage. And now I was encountering her through a new lens. The past several years I’d gone deep into the world of acoustic research for my novel, reading everything from elephant-sound transcriptions to Kandinsky’s colour theory musical analyses, and had come across some of Ono’s early compositional work by way of John Cage. Having written a nonagenarian heroine, I found older women with a lifelong devotion to their work, staring down their own mortality as Ono is, still lodged in my thinking. In her show statement, Ono billed the riverbed as that place “in-between life and death,” and I wanted to know what that place was for her now that she was, well, standing in it.

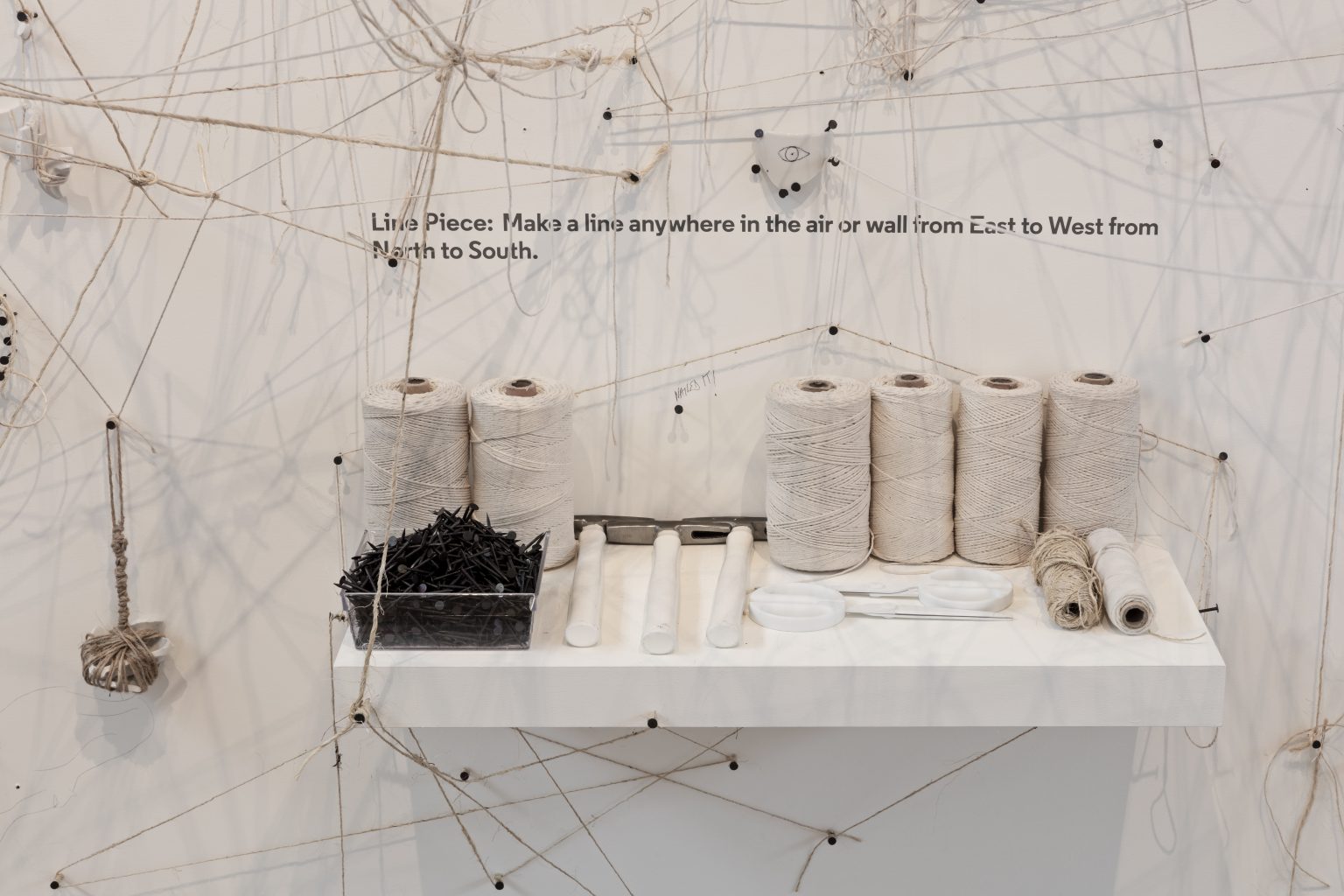

The Riverbed is a three-part call to action. Ono asks visitors to meditate on and then mend what’s broken—cups and saucers—with humble classroom materials such as Elmer’s glue, twine, and Scotch tape, though her vision skews cosmic. Her trademark simplicity and hope, activism and compassion are pared down to simple black-and-white instructions divided into three rooms. As an artist who has put up blank canvases and configured white rooms, requesting people write on or pound holes into them, Ono is uncannily adept at negative space. Which is to say she is a master of producing art that gets conjured in the mind, pushing the viewer into being not only a participant but also a collaborator. An odd thing happens with minimalism, when done right: one experiences both a paring back and an accumulation that makes space for echoes of the self.

I. Stone Piece

Choose a Stone and hold it until all your anger and sadness have been let go.

I read these simple instructions in black Helvetica, stencilled to the wall. I do as Ono says, and in the snaking two-tonne pile of rocks on the gallery floor, miraculously (or from skilfully designed happenstance), I find a stone shaped like a heart inside a heart. Placing it against my chest, I feel it cool on my own beating heart. I slide down the wall and close my eyes, sitting cross-legged.

I first encountered Ono as a child, the way most people saw her in the 1970s, middle-parted, glued to John Lennon. Later, as a student youth-hostelling my way through Europe, I happened upon an exhibition of hers in West London. I was surprised to find that she was a groundbreaking avant-garde artist who, as one of the originators of the Fluxus movement, had worked with Joseph Beuys and performed with John Cage along with her first husband, Toshi Ichiyanagi, a post-war Japanese conceptual music composer. She sang an aria and lay on Cage’s piano strings for his famous “Water Walk” piece. Ono had been classically trained in opera and was also the first woman admitted to the philosophy program at Gakushuin University in Tokyo. She was one of evolution’s wild ones.

I am loath to bring up Lennon, as women artists have been relegated to the “wife of, mother of” footnote in art-history books for too long, but that role is impossible to ignore with the widow of an icon. Lennon had always said he saw her as the artist in the couple, and the fact that almost no one else did was a direct result of pervasive sexist and racist attitudes that still exist.

As legend goes, her art is what he fell for after he famously climbed a ladder at her 1966 London exhibition and peered through a spyglass to read three tiny letters framed on the ceiling—YES. Apparently, he was relieved it didn’t say Fuck you. She’d never heard of him, though she did know Ringo’s name because in Japanese it meant something close to apple. She was seven years older than Lennon.

With the rock against my chest, I think of a friend who is facing her darkest hour, knowing she will be leaving her true love and her two young children once the horrible illness takes her for good. I feel a wave of sadness, and I have no idea how long I’ve been sitting there when a loud hammering sound from the next room almost gives me a coronary. I’m not sure I have enough time to hold my rock until the sadness goes. Does it ever go? But there is something in this quiet engagement that makes me feel different than before I sat with it.

II. Line Piece

Take me to the farthest place in our planet by extending the line.

The next room looks like something out of A Beautiful Mind, a dense thicket of spiderwebbed twine dangling shards of crockery (presumably the peg for a show of conceptual art at a ceramics museum) and scrawled handwritten notes that Ono encourages with her Line Piece dictum. After more than four months of public engagement, the messages are everywhere. Most of them fall into the Hallmark-meets-self-help category, though there are also political statements and ones that veer off-menu too. “Sneak a few blueberries in a stranger’s pocket so they can have a snack later,” someone writes. Snack? I would think stain, but maybe that’s what motherhood has done to me. Still, someone has written “I love you” underneath, and, vulnerable after my rock session, I feel my eyes well up at this stranger-to-stranger tenderness laid bare.

I first read Ono’s originally self-published Grapefruit in my now-husband’s apartment. He was working on an illustrated book, and he said he had been influenced, in part, by Ono’s thinking. When he was a teenager, his elegant bohemian aunt, who lived in Montreal and worked for the National Film Board, had copied out for his birthday Ono’s Earth Piece instructions on a soft piece of paper, which he carried with him everywhere until he found a copy of his own. (The book moves like that.) I would sneak-read Grapefruit in his bathroom late at night, engrossed in its mysterious instructions, such as

Tunafish Sandwich Piece

Imagine one thousand suns in the

sky at the same time.

Let them shine for one hour.

Then, let them gradually melt

into the sky.

Make one tunafish sandwich and eat.

They felt funny and political and beautiful, and I attempted to commit them to memory. It seemed that her art was aimed at freeing people, and what could possibly be better (bigger?) than that?

Her most famous performance, Cut Piece, is simply Ono climbing on stage and sitting passively while the audience cuts off her clothes with scissors. It’s now considered a masterpiece, her ability to boil down centuries of female victimhood-turned-heroic-perseverance into a few tense minutes. That she made this piece in 1963 after giving birth and suffering from what we would now call post-partum depression makes it even more transcendent.

Since 1973, Ono has lived in the Dakota, the historic apartment building in New York’s Upper West Side where Lennon was shot walking up its front steps while she was standing beside him. Every day she must pass by the place he was murdered. She claims she has seen his ghost sitting at his white piano. I’ve often wondered why people continue to live in a place where someone they love has left or died, but I realize she stays because she wants to be visited by ghosts. So when Ono speaks of the riverbed, of its shadow world between life and death, of creating a line, she knows a little of it.

I duck and walk in an awkward bent-crab movement under the low-strung twine web, and one of my ribs catches in my chest. It’s sharp as I suck in air. Bent over, I feel blood pounding in my ears and immediately am aware of a proximity to a long-ago, childlike part of my brain that fuzzes all sense of ego and fills me instead with the capacity for awe and wonder. There is something beautiful and optimistic in collective effort. Anyone who says “Give peace a chance” unironically, as Ono does, knows this.

III. Mend Piece

Mend with wisdom mend with love. It will mend the earth at the same time.

I enter into the industriousness of the last room, with its two large tables flanked with spools of twine, hammers, nails, paper, pencils, tape, and pottery shards. I see adults bent over, stringing and taping with straight backs like kindergartners, focused on their tasks. Though the machine is broken the day I am there, Ono has arranged that good coffee be available to all participants in the Mend room. I am struck by the obvious notion: why don’t we dance and sing and make art freely, unselfconsciously, without judgment, the way we do as children? This in-between place of Ono’s exhibit is crucial for that kind of hopeful collaboration. Because, as Ono continuously conveys, to create means we are alive.

This co-operation has never felt so necessary as in these angry, unpeaceful times. Here she is, giving an invitation not just to participate but also to interact with strangers. As someone so averse to group activities that I dropped out of residence after two weeks at university because of my deep dread of standing in line with strangers at a prescribed time to eat, I am surprised to find myself helping the woman beside me pound her nail into a spot on the wall that is higher than she can reach.

The goateed man in tearaway pants is stringing twine along the door frame at chest height, which means for the rest of the exhibition everyone will have to limbo awkwardly underneath it every time they enter the space. Why is his version of “mending” making people’s lives harder? I can’t help but think that only a man would do this. Ono is a master of showing people how they can think and act, and damned if she hasn’t made him dutifully participate, and us have to figure out how to deal with it.

I am about to leave and my body literally wavers, and then something takes hold that makes me sit at the table. I begin trying to scrape, with my fingernail, tape that has stuck to the roll and is coming off in maddeningly skinny strips. I feel deep tiredness in my body and I want to throw the dispenser on the floor and shout, Why is life so hard!

Instead, I cut three long pieces of twine and tape them to the table and begin braiding. There is hammering and broken-glass sounds and scissors slicing paper. As a child, I spent years with the domestic flurry of siblings, dogs, yelling around me while my mother, who worked and had four children and never sat down, not even to eat breakfast, would spend five quiet minutes every morning French-braiding my hair. It was one of the only times I had her full attention. Braiding makes me calm, but I had never understood this before.

That moment between observing and participating is abrupt but vast and essential if we, too, want to truly be alive. Mend Piece could be a commentary on activism. It is so easy to cast aspersions from the safe sidelines, but what if we checked our cynicism and crossed over and actually did something? Meditating on and then mending what’s broken is a brilliant exercise for our post-internet brains, hacked into by pervasive virtual life. Unlike recent blockbuster shows that have become vehicles for art selfies, Ono’s permits no photographs because she wants you to be present in the experience. What makes her art even more powerful now is the worse we get, the better Yoko Ono gets. She makes us both witnesses to and instigators of change.

So why, at the end of her life, is Ono still known more as the woman who broke up the Beatles than as an artist in her own right?

It could be that society dictates that women artists be accessible and Ono never has been. She is an artist who chose to make ideas instead of sellable works, an opera singer who adopted screeches over her perfectly trained voice, a philosophy major who opted for bed-ins over heady discourse, a mother who admitted indifference after her first child was born, and, perhaps most subversive, a wife who not only told her husband to have an affair but also chose the woman for him. She is someone who seems to say what she believes to be true, not what makes her look good to the public. And in the age of slick personal-brand building, hers is not the advised approach.

Still, Ono is bigger and wilder than all that. As a child in Japan, she witnessed the horror of Hiroshima. She is a woman who lost a daughter to kidnapping then a cult, a husband to a killer, and yet still she is devoted to peace, to freeing people. And maybe now—confirmed by the over twelve thousand visitors who filed through the Toronto exhibition, more than double the museum’s optimistic projections—more than ever, we want to be freed.

I can perfectly picture the bike ride to the museum, but when I try to recall, only a couple of weeks later, the ride back, I am completely blank (again by miracle or by design?). I do remember thinking about what Ono wrote in the show catalogue: “With our wisdom, love and creativity we will mend what has been broken, or about to be.” She asks for your total attention, for you to give and leave a piece of yourself. And with this work, she might just have tidily answered the eternal question for us. There is no end to life. Art proves it.

Images from Yoko Ono’s The Riverbed exhibit are courtesy of the Gardiner Museum and printed here with their kind permission. Copyright © 2015/2018 Yoko Ono.

Heidi Sopinka has worked as a bush cook in the Yukon, a travel writer in Southeast Asia, a helicopter pilot, and a magazine editor, and she is co-founder of Horses Atelier. The Dictionary of Animal Languages, her first novel, was published this year in Canada, the U.K., and the U.S. and is being translated into Polish