Total facts known about Al Purdy: There is a statue of him in Queen’s Park in Toronto. He was called the “People’s Poet.” The statue is called the “Voice of the Land.” I’ve read maybe twelve of his poems. I like their candour and plain images. The way his completely overwrought emotions are always busting out from behind the simple truth. I don’t like their misogyny or racism. Maybe this is because both my grandfathers died before I was born. I never had the chance to develop affection for old white men with tobacco breath and what they say when they’re exhaling. I’ve never loved one.

Al owned a house—a large cedar A-frame in the Ontario countryside—with Eurithe, his wife. This house is now a writing residency. It feels like a cottage, with a lake at the edge of the property and everything made of wood. He and Eurithe built it and lived there with their kid, and they were poor. After Al died, people fundraised to buy the house and fix it up and pay poets twenty-five hundred dollars a month to live there, a salary I imagine would have pleased Al very much, once upon a time, if it had been offered to him. Maybe at a certain point it was, when he got famous. I know very little.

From October to December of 2015, I lived in Al’s house, on that salary. That this position had been offered to me was astonishing. I had not expected anyone to believe the lies on my application. These were statements like, My whole career I have toiled in the shadow of the man with the white, flapping hair. When I am passionate about the way two words sound butting up against each other, I start a bar fight. I am one of the people. Yeah, that’s right. I’m a person. I did not say these things. I implied them.

I began my stay with a resolution: So long as I was living in the house, I would learn as little about Al Purdy as possible. I wanted to preserve the purity of the few facts I knew, and not have them distorted by this gift. I wanted my mind to be free, like a professional’s. Though I had lied, I wanted now to begin on a path of honesty. I was not naturally the sort of person who was very interested in Al Purdy. My nature was to be more interested in his wealth. If you find this ironic, well, so do I. But it’s the truth.

The people who did all the work to fundraise and fix up the house and administrate the residency acted like what they were doing was for Al, but really it was for me. It was incredible. They tore up the deck and the floor. They moved rocks around and rebuilt a stone chimney. They made intricate hors d’oeuvres and fed them to rich people and hungry people pretending to be rich in order to get hors d’oeuvres. I never saw the hors d’oeuvres, so I have to imagine them. They were for me.

Though sometimes dishonest, I am a grateful person. It didn’t occur to me to mind that it wasn’t Gwendolyn MacEwen’s house I’d been given, or Dionne Brand’s house with her still in it, or Nicole Brossard’s house with her still in it, or a house my friends A and A and D and E and J and L and N could all share permanently in a world outside of time, like in a sitcom, or my own. Well I’ll admit it occurred to me, now and again. When it occurred to me I thought that maybe instead of being where I was I should be out building something. N and I talked speculatively about architecture—how tall and how many windows, what kind of view. What country. Gwendolyn MacEwen was not the home-owning type. Mainly what she had was eyeliner. There’s a little bust of her in a parkette just the right size for pigeons.

I was turning slowly into a statue too. In a way you could say people commissioned it, paying me to sit there. A chilly way to have a body. And of course there was no official source of heat. The fireplace ate a lot of wood that mostly did not exist. Or it was green. Wet. But I loved being in the house. I worked like a maniac. I developed a shoulder injury. I went for long jogs in the autumn countryside past horses and cornfields. The jogging part is a lie. The horses are true though. I got deliciously lonely. There were big windows, mostly without curtains. At night I would dance wildly with my own reflection. My favourite song to do this to was about werewolves. Finally the neighbour, a late-middle-aged man, introduced himself. What he said was, “If you ever get cold, there is always a warm bed over here.”

It was a hard environment in which to stick to my resolution. I was surrounded by information. The information was in the chairs and the cups and the books and all the records that could not be played and the broken devices for playing them. It was tantalizing. My gratitude made me vulnerable. My need to sit down sometimes and drink tea with brandy in it and stare at the wall (which was covered in framed poems and newspaper clippings and telltale cobwebs) made me vulnerable. I had to be crafty. Each morning I walked past the overflowing bookcases without touching anything, like in a myth. I sat down at my table by the window and read my own books. They were by Morgan Parker and Bernadette Mayer and Eileen Myles and Ali Blythe and Fred Moten and Liz Howard and Juliana Spahr and Leanne Betasamosake Simpson and Marcel Proust and others. They were very nourishing. At night I was sometimes afraid of ghosts. I never looked behind me.

Lots of people visited me at the residency. Women, one or two of whom I had a big crush on. A few men, one of whom became my lover. They were smart and fascinated by everything. They looked at the shelves and wanted to show me what they found and looked things up on YouTube and said, “Hey oh my god come watch this clip.” They told me Eurithe did most of the construction. They told me the bust of D. H. Lawrence was a bust of D. H. Lawrence. I tried not to listen. We put a headlamp on him.

Then came some pilgrims. They pulled up one day in a car. Nine of them. They acted as if they had come to see Al Purdy, but really they had come to see me. I let them look. One pinned a pretty letterpress version of an Al Purdy quote to the wall, something about little gold hairs, and it hung there like a fishing lure, not quite legible from the kitchen table.

Something was happening to my body. It was like puberty, beyond my will. I looked in the mirror one day—there were mirrors everywhere in the residency—and saw my plaid shirt and my boot-cut jeans and short, tousled hair with a branch stuck in it, and I realized I looked genuinely butch. I had always been more or less feminine.

Since childhood I have liked to dress up as men. For fun, like on Halloween, the little sections of life that are safely cordoned off, like where the horses are. What keeps the horses in is a single piece of twine. It’s incredible.

I like jokes and I like irony, but I also know there is no such thing. Gestures are actions. Games are real life. Residencies are where you live. One way to explain the photographs I took is that I was living in Al Purdy’s house and the moon was full and I was becoming him.

Like everything, it was a collaborative process. I posed for photographs with my beautiful guests. They were like photographs that had been taken in the past, where we had not been invited. There were limitations to our stance. These related to our bodies and the bodies we were imitating. We died laughing. There is a statue of me, now, in Queen’s Park.

I learned something. I didn’t mean to. Al Purdy was a body. He had an enigmatic, downturned smile and favoured his right hip. I think it must have been injured. When he wore a shirt, which was not especially often, he left four buttons undone. He lived in his time and place with his family. It was summer. Not everyone was invited. His hair behaved as if constantly trying to escape his head. He liked to eat chips or possibly deli meat. Either way, he was not ashamed. He held it up for the camera. He was good at it. People are. He did it with his friends and family. I did it too. I was trying to be free inside my circumstance, which looked strangely like his. Freedom did. It was ambiguous. The food. And I couldn’t park the car between the trees like that, at that angle. I tried until a man said stop. He was not my boyfriend. He cared about me, though. In that moment. And the car. My freedom felt funny and uncomfortable and not like freedom at all but a pose. My freedom felt chilly in the autumn air, and like a joke, the mean kind, with a kernel of truth in it.

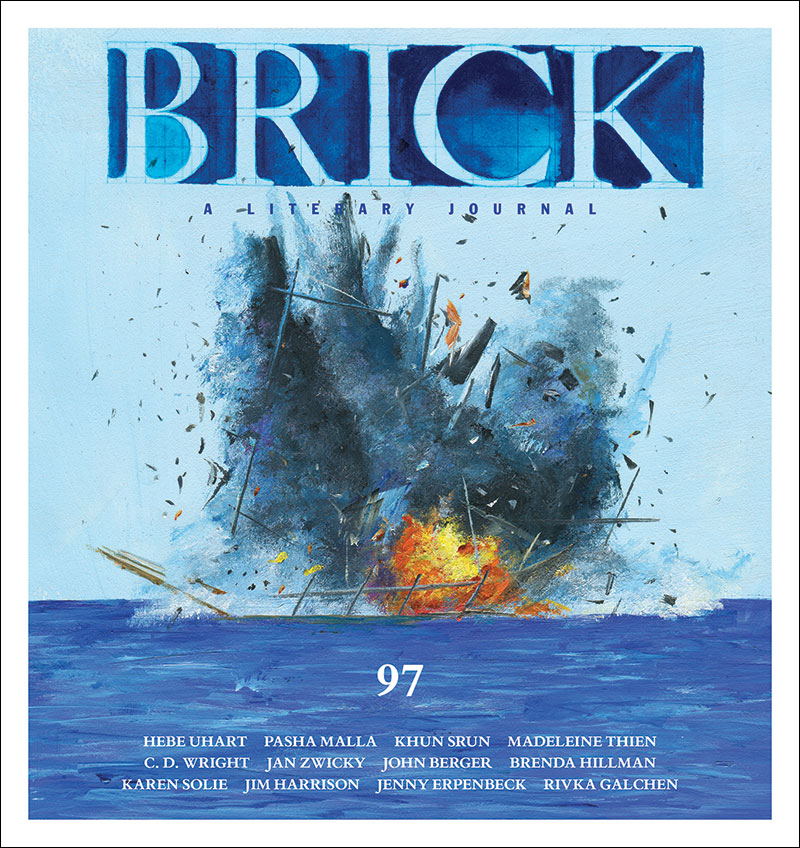

Visit the gallery to view the images that appeared with this piece in print, plus extra web-exclusive photographs.

Helen Guri is the author of Match, published by Coach House Books, and two poetry chapbooks, Here Come the Waterworks and Microphone Lessons for Poets, both published by BookThug. She lives in Toronto, where she is working on a book of lyric essays.