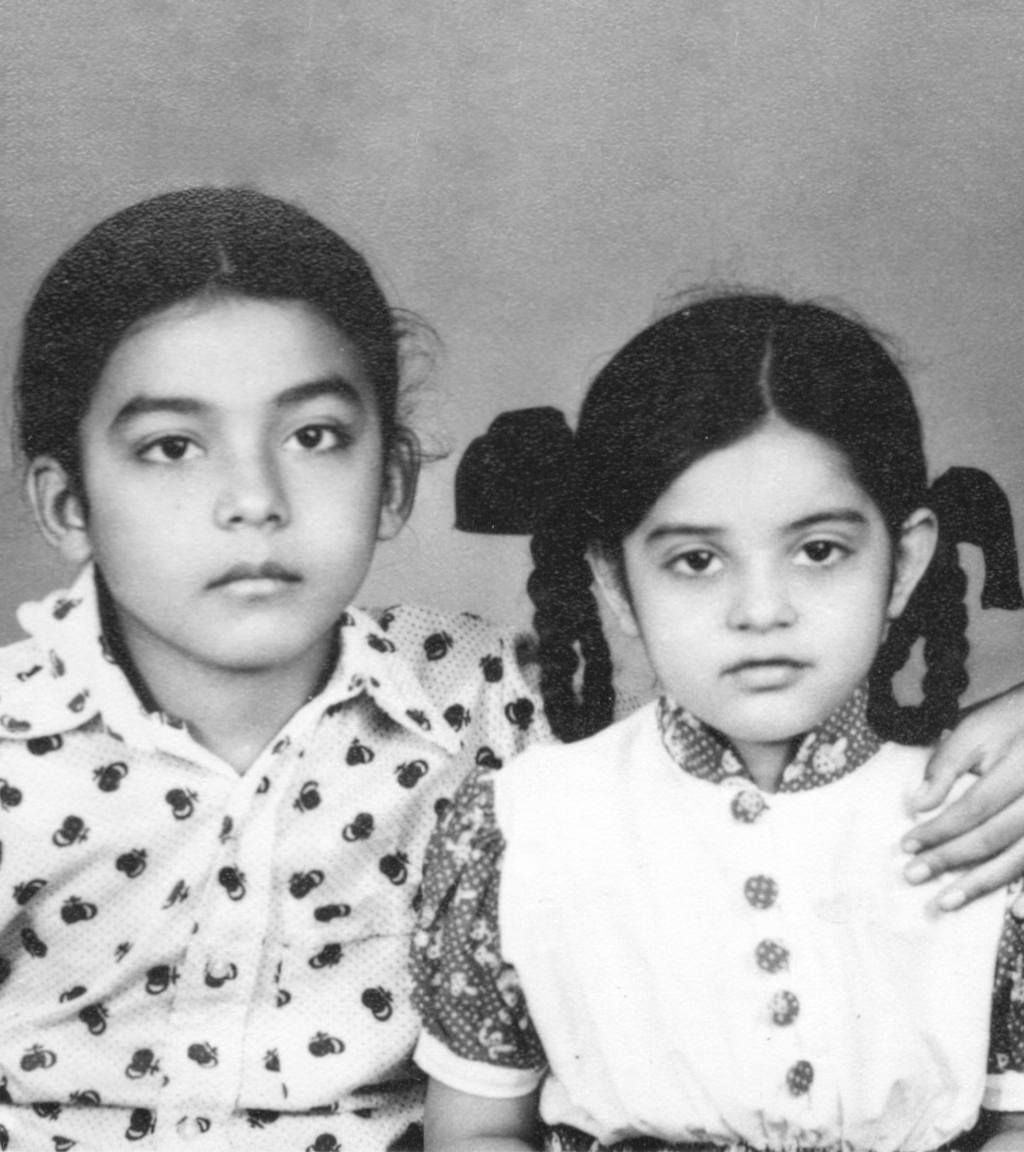

I was around thirteen and my sister was around ten when during a moment of severe panic my parents came up with a concrete, no-nonsense plan to lengthen our bodies by eight or nine inches. Despite being involved in sports, my sister and I had stopped growing at the expected rate and this was embarrassing, especially when guests arrived for dinner. Our biweekly height measurements, pencil marks on the dining-room wall, seemed to have achieved a stubborn steady state. Normally my parents disagreed about everything and disagreed strongly, but they latched on to the body-lengthening program like some made-in-heaven team. We will make sure, my mother said to my sister, you end up taller than me. We will make sure, my father said to me, you end up taller than me.

In the orchard behind our house was a battalion of cherry and apple and pear trees. The regiment carpenter was commissioned to fasten a softened wooden pole horizontally between the branches of two neighbouring pear trees. My mother calculated the exact number of minutes we were supposed to stretch from it daily. No excuses. We were also encouraged to do stretching (rather pole-dangling, rather lamakna) exercises during breaks between homework and also before and after any form of entertainment.

At first my sister and I would dangle from the pole for hours on end, the ordinary hanging from hands monkey bar–style dangling, but with time we were bored and introduced some daredevil innovations. We dangle—d upside down. We lamak—ed from the back of our knees hooked over the pole. Asi u’ton thha’le, thha’lon ute, godde’yan ton, har taran lamakna. A few days later, to our surprise, we found we were no longer competing against each other. For some strange reason we started competing against our own selves.

However, the pencil marks on the dining-room wall showed little advancement. My mother said only spoiled children receive instant gratification. So we would get back to work. You must work to be tall, she said. And you do not want us to make a long list of all the advantages of being tall in this world.

At times while doing her homework my sister would watch me lengthen from her room window. The exercise became so normalized in our family, no one even passed a remark about pole-dangling, as if it were simply as normal as the mountains or Morse-code dots and dashes or long threads of Holocene smoke rising from coal-heated bukharis (or my father’s capricious inspection stick). She only laughed whenever I fatigued and fell big-boulder-like on ground.

One day my fresh pencil mark revealed that I had actually lost height by a few millimetres, and I ascribed this to my constant falling from the pole. By the end of the eighth month, both my sister and I were severely injured. Legs, arms, bums, even noses. Luckily for us the program received termination orders then. Whenever in our adult lives we tried to return to those eight wasted months of our childhood, my father said to me, You would not have reached even my height otherwise. My mother said to my sister, You would not have even reached my height otherwise.

Jaspreet Singh is a novelist. His memoir My Mother, My Translator is published this fall.