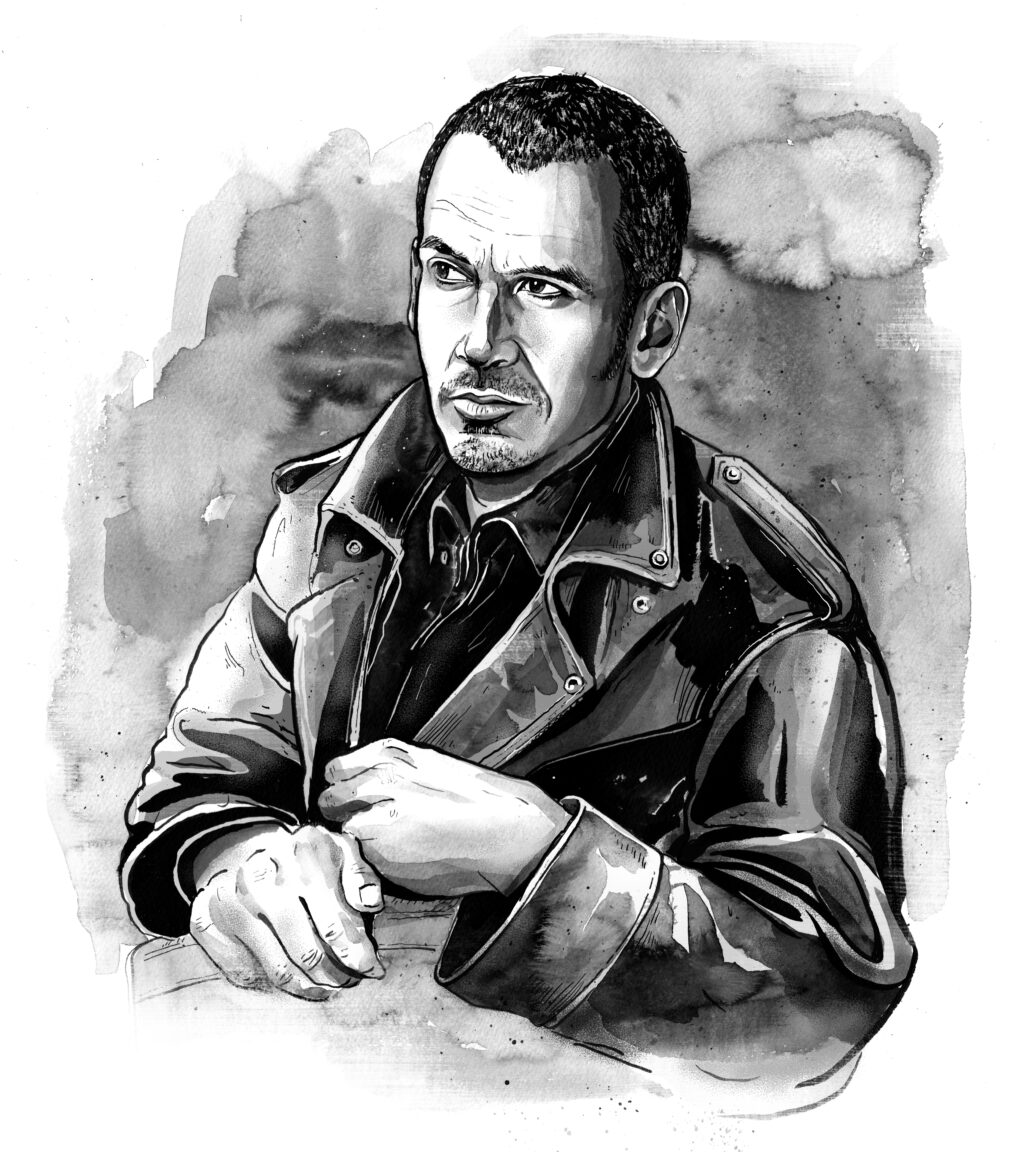

Three months after Steven Heighton’s passing, I keep returning to the opening lines of Tomas Tranströmer’s “After a Death”: “Once there was a shock / that left behind a long, shimmering comet tail.” The residue of the shock hasn’t settled for a lot of us; it throws a static of disbelief into the world’s everyday signals. But I prefer to see the comet as the event of a life that lit the landscape, that left in its wake an extraordinary array. Reading Steve’s poems will always be like witnessing the flare when a phenomenon enters the atmosphere.

Steve’s poetry seems to acknowledge a Romantic inheritance in its devotion to mystery, to the natural world, to dreamwork and intuition, and to its task of bearing witness to climate crisis, injustice, and war (recalling responses in poetry and visual art to the Industrial Revolution, and the social justice and land-use issues it created). It doesn’t, however, indulge in affectations the Romantics are usually charged with, and any such designation pays short shrift to the complexities of a writer’s life and work. Steve’s poems are suspicious of writerly melancholia but not dismissive of it. Any poet will cringe in self-recognition at “The Minor Chords,” from The Waking Comes Late (2016), that “lauded colleague’s cocktail / froideur.” His many elegies, his celebrations of life’s small shining moments, are nostalgia-free, as much as we can ever be nostalgia-free. Or, they are nostalgia-aware. In Patient Frame (2010), the speaker of “Home Movies, 8 mm” registers absences in the narrative or failures of attention not as erasing clues that would explain experience but as what might have opened the mystery further.

I know memory—

what these reels were meant to fortress,

aims the same fickle lens, leaving gaps and blurs

in the record, but what of the eye itself, as it glides

over a lifetime’s loves the same way, careless

and rushed, a manic amateur—

and the little reel clicks down inside?

If I could start over, I would stare and stare.

The love poems—whether to a lover, a child, a parent, a friend—recognize the distance between the self and other without attempting to solve it. Love remains an active inquiry, an affirmation with a difficult question inside, precarious and undeniable. “Constellations,” from The Address Book (2004), ends with a daughter posed in a dark hallway, “one foot slightly raised— / the Dancer, he supposed,” with glow-in-the-dark stars from her bedroom stuck all over her:

and all his love

spun to centre with crushing force, to find her

momentarily fixed, as unchanging

as he and her mother must seem to her,

and the way the stars are; as if the stars are.

An unfailing though at times circumspect curiosity unifies the elegies and odes, laments and celebrations, love poems and poems of witness. There are many quests among the poems, rituals sacred and secular, from burial ceremonies to running with his dog “into cityless time—the reliquary forest still cached / with ancestral smells.” And Steve wrote often of death. Always, the poems ask how we might fully be here for others and for ourselves in the proximity of not being. What is this in the face of that? His compassion, extended equally to civilian and soldier, isn’t the shy kind. It’s held up like a lamp in the forest of some complicated (to put it mildly) souls. His first collection, Stalin’s Carnival (1989), includes in its title section remarkable works of translation and invention that imply where a self-deceiving romanticism can lead. His later work continues to ask what it means to want to understand acts that resist comprehension, while not pretending in the least to understand them. And his is a compassion that takes on the responsibility to condemn amoral acts of war and abuse.

Reading him, I remember our conversations over the years about why as poets we are sometimes afraid to align ourselves with what we believe in. Why, indeed, we can be reluctant to admit we believe in anything. Why we are afraid of sincerity, uncertainty, beauty, lyricism. Why we listen when we are told no one wants to hear about our dreams. In “Some Other Just Ones,” a poem whose first and final lines are from Jorge Luis Borges’s “Los justos” (“The Just”), he writes of

Those for whom sustaining hatred is a difficulty.

Surprised by tenderness on meeting, at a reunion, the persecutors of their youth.

Likely to forget debts owed them but never a debt they owe.

. . .

These people, without knowing it, are saving the world.

There is courage in writing poems that draw from sources not always in fashion—more so in living in a way that does not allow these sources to stagnate or become self-serving. Steve was a poet who believed in beauty and in truth while remaining skeptical of their universal applications, their comforts, or whether they exist in any sure sense beyond moment and context. He believed in the value of pursuing this question, that it constitutes a kind of excess inside experience where meaning might reside. “From the start,” Steve writes in the preface to his Selected Poems, “the part of my mind that conceives real poems (as opposed to the ego that forces fakes) seems to have worked to subvert my tendency to overthink and over-explain the world. It has recruited me into the role of stenographer to my nightmind.” Efforts to articulate intimations of meaning will only ever result in semblance—the semblance of a semblance, really—and Steve notes that the impulse “has nudged me toward difficult, hence usefully estranging, languages and the act of translation.” He calls the results “approximations.” Like dreams, he writes, translation “demotes the bossy ego, noisy ego, since translators must submit and apprentice themselves to the source text and labour in service to it.”

It was both a joy and a daunting prospect to edit Steve’s Selected Poems in the summer and fall of 2020. Or rather, to assist in their selection, as the choices were made in a collaboration guided by Anansi’s poetry editor Kevin Connolly. There are so many good poems, so many beautiful approximations living their parallel lives in companionship. And then there are the poems that appear in different versions across collections. Another of many possible choices would have been to include these returns. But there is never enough room, is there? Never enough time. This “never enough” is itself a restless spirit in the book.

Revisiting Steve’s poems reacquainted me with my excitement on discovering The Ecstasy of Skeptics (1994) when I was beginning to write. Lyrical, self-aware, conflicted, the poems to me felt timeless while also grounded and relevant. “A Psalm, on Second Thought” is as apposite a struggle with personal poetics now as it has ever been.

I’m not afraid of taking this harp

down from the willow

to sing—though no one

trusts song much anymore, or the singer—

. . . .

I’m not afraid of easing this harp

out of the limbs of the dying

willow to sing, but who can sing, and not become

the laureate of a state

of legislated greed?

And if my tongue forget?

I’m afraid

at times,

of taking this harp

down from the dead

willow to sing

Rediscovering the grit of Steve’s poetics, I also heard the music. The technical skill and sheer pleasure in line, in cadence, that so impressed and thrilled me then still does. This is the first stanza of one of his early poems, “A Perishable Art”:

I found my mother’s footprints in the snow

still fresh, she’d passed this way only moments before.

Her tracks climbed and crossed the treeless hills at the skyline.

Her heels were halfmoon gouges in the white crust, glowing.

The instinct of that first comma, the clambering up out of the pentameter line, the snow suddenly glowing in the mind. From the beginning, Steve had an impeccable ear and an eye for structure, as well as a talent for the image. He mastered the tools of the art because he wanted to communicate. He writes in his preface of his late return to music, to the words that when sung can’t be overlooked, when “at last nothing stands between your heart and your hearer.” I think this desire for immediacy also speaks from the page. When a poet integrates influences, skills, intellectual rigour, and sensibility, it creates the intuition for how to approximate the charge of excess inside experience—that tonal feeling, the heart, the ghost in the machine.

I was writer-in-residence at Queen’s University in Kingston in 2017 when Steve was starting work on some new poems, and we met in a pub to talk about them. It was late fall. Gord Downie had died the month before and, even in the icy wind off the lake, people were playing his songs on street corners, handmade signs and graffiti everywhere downtown. We spoke of this, and of the consolations of music and Steve’s hopes for his own. The music of Steve’s poems has never been predictable. It works at the edges of metre, line endings leaning over it or drawing back, creating a momentum with the centre of gravity, the core strength, that enables grace. (“Desire itself is movement,” writes T. S. Eliot.) The new poems do likewise; but there is a change, subtle yet tangible, as if it’s not the music that’s altered so much as the room it’s played in.

In “Christmas Work Detail, Samos,” written out of Steve’s experience volunteering for refugee organizations in Greece, the hexameter is troubled by the question of how to help in a state of helplessness, when one’s actions are both necessary and insufficient:

In the olive grove on the high ground, facing west

into rain, we dig graves for three men drowned

in the straits—Syrians, maybe, dispossessed

of everything by the sea, so there’s no knowing

for sure.

“Easter on the Salish Sea” is a brief lyric of imagistic clarity whose common time pares down like the echo after the needle lifts from the record.

Soles cut numb in clamshell shallows.

Turn shoreward: sheer to the zenith,

steeps of old growth are razored

clean to soil, a stubble of umber.

And the last colossus, shorn

to limbless, barkless lumber,

floats like a gangland corpse

face down in shorewater,

shrinking, as dead things do

in Ovidian dreams, as if such mythic

worlds could cease, as if

this were a dream.

Perhaps the dimensions of the new room are scaled to the tension between helplessness and action, insufficiency and necessity. It’s a big room; one feels the space around these poems. It requires voices to fill it. As Steve writes at the end of “Better the Blues (Unplugged),” “better the blues / than no-song.”

Among the several voices of the new poems are approximations: Kóstas Karyotákis, Jacques Prévert, Nikos Kavvadias, Gottfried Benn. On that evening in 2017, in the warm pub with our whiskies, we talked about his draft of the Benn poem, “Listen . . . ,” based on the original “Hör zu.” Something not quite right, Steve said, at the end of the second stanza, with the dog. Or rather, the word dog wasn’t right there, in the approximation—too short, wrong sound, and not up to Benn’s dark mischief. Hound was closer, but no. I don’t remember who said it first, where Weimaraner came from. But there it was, and after a few minutes at the stress test, we began to laugh—the big drooling silvery head, the German breed nicknamed “the grey ghost,” the rhyme with radiator. Hurray! We clinked our glasses, laughed harder at the ridiculousness of our joy as the pub’s few other patrons looked on bemusedly. It was a joy in excess of what one word might warrant. It had something to do with the shared understanding of the moment, a moment made possible by Steve’s refusal to settle, neither in terms of craft nor of inquiry. Deliberations over poems in his Selected often came down to basic questions: Is there a kind of truth? Is there beauty? Is there music? There is.

Karen Solie’s most recent collection of poems is The Caiplie Caves. She teaches poetry and writing in Canada and for the University of St. Andrews in Scotland.