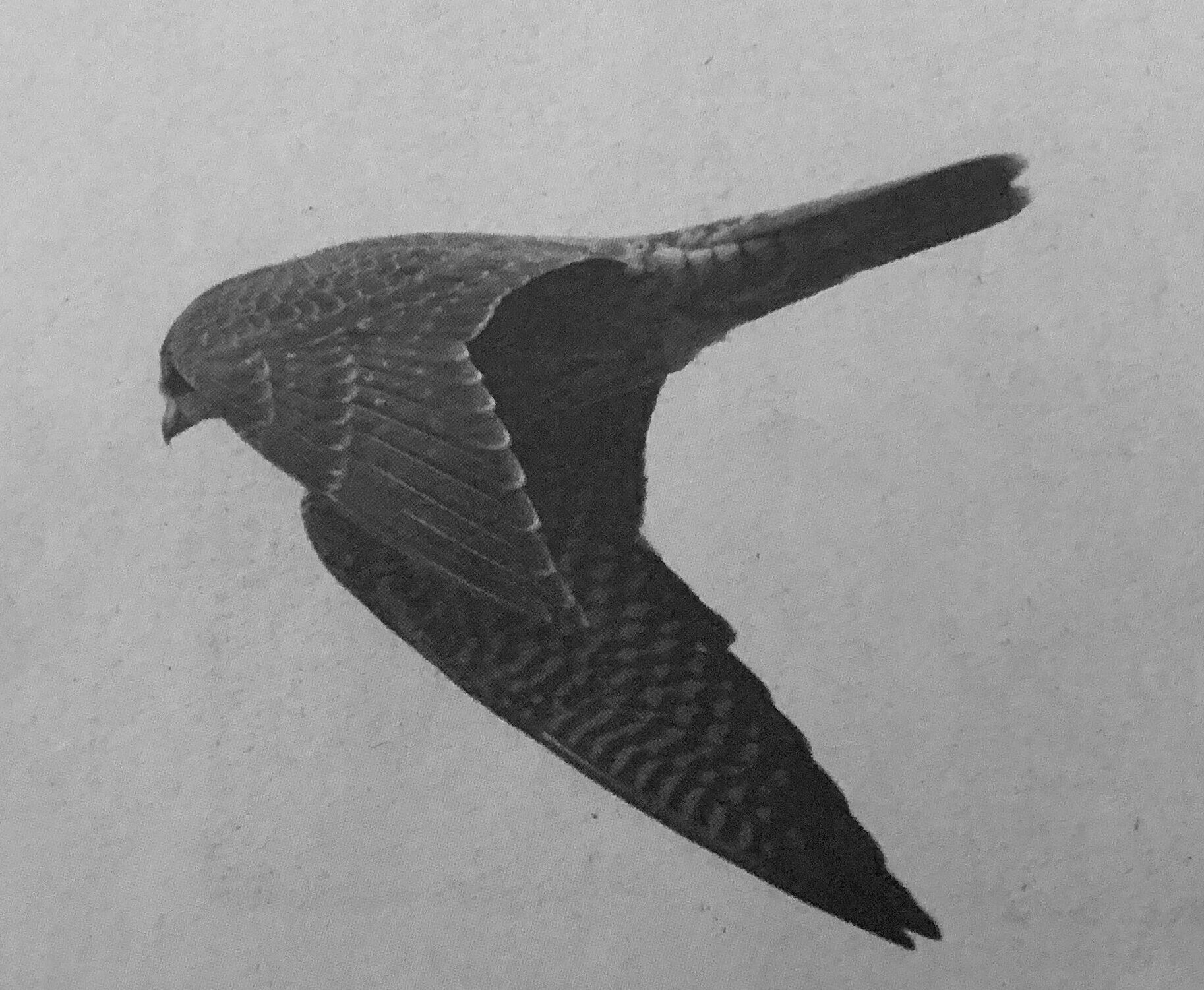

What is a person but an animal? Women, especially mothers, are raptors. I come from people who could fly. From above, one hundred feet in the air, approximately ten storeys high, the red-tailed hawk perceives its prey—a grey-haired mouse. A silver Subaru speeds down the highway, my mother gripping the steering wheel. Writing is no different from camera work. I focus in on the turquoise-framed glasses that rest on the bridge of my mother’s broad nose before zooming the lens out to capture the red of her copper-toned skin, the salt and pepper of her hair, shaved low, close to the scalp. My mother frequently spots hawks in the sky while driving. She cranes her neck beneath the windshield, her grin widening like the wingspan of a bird as she exuberantly exclaims: “There’s Grandma!”

My mother’s smile disarms and devastates. Up close, I am her spitting image. People, however, aren’t always as they appear. My grandmother, who is also a hawk, began to mistake me for my mother as her dementia worsened, often calling me by my mother’s name instead of my own. Dead for well over a decade, my grandmother lives on in the form of birds of prey. Only after my grandmother’s memorial service, when a hawk suddenly perched on my mother’s back deck, was the family folklore developed that these types of appearances were actually familial visitations, that a winged creature could be a vessel for a departed one’s soul.

The first episode of the documentary miniseries High on the Hog: How African American Cuisine Transformed America focuses on Benin. Titled “Our Roots,” the episode contains a scene where a voodoo practitioner talks about a powerful voodoo man using a hawk to transport people to safety to save them from being enslaved. Hearing this story reminded me of one of my favourite books from childhood: Virginia Hamilton’s collection of American Black folktales titled The People Could Fly. The sleeve of our hardcover copy of the book bore a light grey border that framed a painted illustration of Black folks flying. In the centre of the flying collective is a Black woman; her blue-and-white-checkered skirt floats above the clouds. In the woman’s arm, a baby peacefully sleeps. The folktale “The People Could Fly” begins as follows: “They say the people could fly. Say that long ago in Africa, some of the people knew magic. And they would walk up on the air like climbin up a gate. And they flew like blackbirds over the fields. Black, shiny wings flappin against the blue up there.” When I first read Toni Morrison’s Sula, I circled every mention of a bird in the novel. I remember holding my breath as I encountered the beauty of Morrison’s language. I recall being particularly mesmerized by a sentence that foreshadows Nel and Sula’s future: “It would be ten years before they saw each other again, and their meeting would be thick with birds.”

The family that prays together often has a history of violence, but we will get to that later. As a child, I attended Pilgrim Congregational church with my grandmother. My grandfather stayed behind, as did my mother—her hand waving from the doorway as I glided into the backseat of my grandma’s green Toyota Camry holding a plastic bag full of Cheerios. Once inside the wooden pews, I spread my tiny arms out like wings; they hovered above the miniature cups of communion wine as I pretended to direct the choir. United Church of Christ service on Sundays and weekday Catholic mass, a feature of thirteen years of Catholic schooling, taught me little about how to live in my own Black body, left me even less prepared for how to navigate the world as a queer woman headed off to Howard University in Washington, D.C.

At Howard, I earned a Bachelor of Science in psychology, which served to synthesize a scientific knowledge of the mind with the spiritualism I’ve inherited from my mother. Coined by German neurologist and psychiatrist Klaus Conrad in 1958, apophenia is the human tendency to unreasonably perceive connections and meaning between unrelated things. I continue to grapple with reconciling this Western European mode of thought, as diagnosed by a member of the Nazi Party, with the Indigenous wisdom found in Robin Wall Kimmerer’s Braiding Sweetgrass, where she cites an alternative method of cognition: “Native scholar Greg Cajete has written that in indigenous ways of knowing, we understand a thing only when we understand it with all four aspects of our being: mind, body, emotion, and spirit.” There is a strained link between what formal psychology deems misperception and the intuitive ways in which Indigenous and Black people operate as seers. How curious that when Kimmerer describes the process of navigating two different worldviews, she uses the language of flying: “There was a time when I teetered precariously with an awkward foot in each of two worlds—the scientific and the indigenous. But then I learned to fly.” As a writer, when I take up my pen, I employ my wings. I feel deeply in my extremities the presence of both my mother’s and grandmother’s hands. Between those hands flows an exchange of metaphors—a Black, psychic traffic of meaning-making.

In Helen Macdonald’s memoir H Is for Hawk, she details her attempt to train a goshawk as a means to cope with the sudden death of her father. Drawing a real-life literary parallel with H Is for Hawk, I decided that G is for goshawk or Grandma. In remembrance of my grandmother and in an effort to keep her legacy alive, I became committed to fostering my mother’s love for her own mother through Grandma’s transfiguration into a hawk. I wanted my mother to have the opportunity to make myth a reality, to grieve my grandmother with goshawks, one of the most vicious predators in the animal kingdom.

While working as a Colorado College librarian, I would regularly rummage through the “withdrawn” shelves, where materials would be stored after being removed from the catalogue. A bibliophile, often plagued with the urge to hold on to everything, I would frequently take many items home with me. These homebound, rescued treasures included multiple back issues of the Navajo Times. I was delighted to discover that in the pages of one of the newspapers were photographs of a northern goshawk gliding through the sky above Tsoodzil, the mesas of the Laguna Pueblo tribe in the distance. In the Navajo language, Dinétah means “among the people” or “among the Navajo.”

The scientific name for the northern goshawk is Accipiter gentilis, the Latin word gentilis meaning “of the same family or clan,” a connection to the history of falconry as a practice reserved for nobles. I quickly learned the inaccessibility of falconry. Helen Macdonald’s father was a respected British photojournalist who died suddenly of a heart attack in London. My mother’s mother was a long-retired New York City social worker who died after years of complications from Alzheimer’s in St. Louis, Missouri. Helen Macdonald had been a falconer for years at the time of her father’s death and had the money, resources, as well as the wherewithal to purchase a young goshawk. I was a college librarian drowning in student-loan debt who had never even owned a pet parrot. However, I forged ahead on the strength of my mother’s word and worldview.

What my mother and I lacked in qualifications, certification, and training we made up for in the complexity of our grief, our proficiency at innovating love. My first lesson in ornithology came the day a bird of prey landed on a branch of my maternal family tree as a sign, an omen, a harbinger. Just as the rings of a tree are concentric circles, my grandmother’s death, in my mother’s view, was simply the phase preceding her rebirth as a bird. No knowledge of linear time, no physics formula or law of nature, could change that fact. I’m sure that those who believe that nonsense is nonsensical will deem this notion foolish, but those wise enough to understand that nonsense is rooted in sense will find what I am saying to be true.

I’d learned, soon after moving to Colorado Springs, that the famed luxury resort the Broadmoor offered their guests “falconry experiences.” The harsh reality of not having the correct credentials is that one is reduced to the status of a spectator. From the position of a sightseer, one must pay a high price for exclusive access in the form of leisure entertainment. With money I did not have, I took my mother for an overnight stay in the Broadmoor’s cheapest room. Charging everything to my American Express, I gave my mother the “once in a lifetime experience” of a falconry beginners lesson. After an overpriced yet decadent breakfast buffet, also charged to my credit card, we hopped into a van with a group of vacationers. I felt like a tourist in the city where I lived as we rode across golf courses to be introduced to the Broadmoor’s falconer Roger and his birds of prey.

Not very interested in the proper identification of birds or in the retention of novice-level falconry information, my mom and the falconer bumped heads. Repeatedly, Roger corrected my mother’s mistakes. When presented with a male hawk, my mother remarked, “She is so beautiful!” Roger’s response: “Now remember, this bird is a he. You can tell it’s a male because of its smaller size as compared to the female.” During the flight demonstration, when my mother called the bird Grandma, Roger interjected, explaining again that he had named the bird Goose because it was as silly as a goose. When my mother called her mother a red-tailed hawk, Roger stepped in to educate us that Goose was in fact a Harris’s hawk. There is power in the authority to recognize and name, to assign a singular, static meaning. What I had envisioned as a spiritually moving experience, an in-person reunion of my mother with my deceased grandmother, dissolved into a comical game of mis-recognition. My mother and I had not come for a paid experience in the pronoun-policed language of sex and gender binaries. We had not sought out a fancy expedition into respectable correctness. The falconer could not see us from his vantage point. The knowledge that a variable can hold multiple values went right over Roger’s head. I hope, dear Reader, that at least you know a bird can be many things at once.

In falconry, a mews is a structure designed to house one or more birds of prey. I like that the word mews sounds like muse. Mnemosyne, the Greek goddess of memory, gave birth to nine daughters—the Muses. Sometimes when I write, I invoke my grandmother as a muse. I remember what it felt like to watch and wait as she slowly lost her memory, transitioning from living on her own to an assisted-living facility and then, finally, a nursing home. Loss happens in stages. At first, you lose your driving privileges: a street full of side-swiped cars and a police officer at your doorstep with a severed side-view mirror in his hand. Next, you lose access to appliances: the blare of a smoke alarm’s scream, the fire in the kitchen a result of the aluminum foil–wrapped muffin you placed inside the microwave for five minutes. Last, you lose all sense of time: a Styrofoam cup of vanilla ice cream served as dessert with lunch, fully melted in your handbag by the time you retrieve it to give to your granddaughter as a treat during the nursing home’s evening visiting hours.

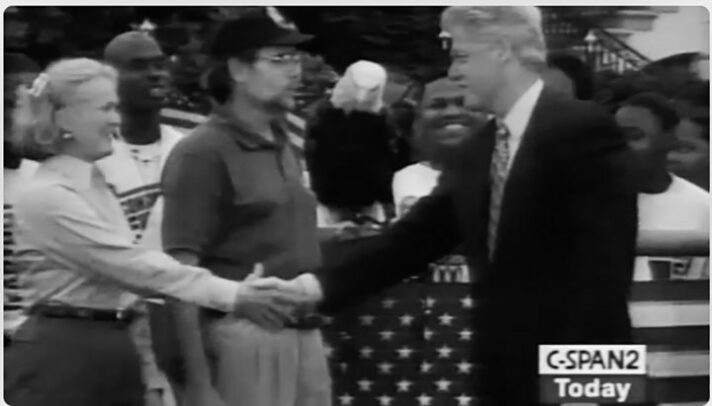

On a forever hunt to find Black falconers, I discovered the master falconer and licensed raptor specialist Rodney Stotts from Southeast Washington, D.C. “All my birds are named after loved ones who have passed on, so you are never alone, they are flying above looking down,” Stotts proclaimed from my computer screen. I shot up in bed as I watched the online screening of the documentary The Falconer, which weaves Stotts’s present-day mission to build a bird sanctuary with his past and continued experiences of social and environmental injustice. Here, on film, was a man I had never met echoing my own mother’s beliefs. A scene in The Falconer from earlier in Stotts’s life shows his involvement with the Earth Conservation Corps, an organization on a mission to remove the bald eagle, the national symbol of the United States, from the endangered-species list. In the foreground of my screen were Al Cecere, American Eagle Foundation founder; Jody Millar, bald eagle recovery coordinator for Fish and Wildlife Services; Challenger, a bald eagle; and President Bill Clinton. In the background was a sea of Black faces, the young people making up the members of the Earth Conservation Corps.

On July 2, 1999, the bald eagle Challenger was an invited guest at the South Lawn of the White House. One day before my birthday and two days before the last Independence Day of the century, President Clinton used the occasion to push for Congress to approve a one-billion-dollar Lands Legacy Initiative to preserve critical wildlife habitats and fund permanent financing for green spaces across the United States. Secretary of the Interior Bruce Babbitt took to the podium to celebrate the Endangered Species Act, which had helped to bring back the bald eagle. Levar Sims, a twenty-one-year-old member of the Earth Conservation Corps, offered President Clinton’s introduction. In his remarks, Sims speaks of growing up in the Ellen Wilson housing projects; he shares how after the near extinction of the eagles, he would now have the opportunity to teach his two-year-old son what a bald eagle looks like in the sky. Toward the conclusion of Sims’s introduction, he makes an eloquently nuanced twist on the word endangered: “Mr. President, I think you might know during our four-year eagle effort, we got to name six eagles after corps members who were murdered. Last year, we named one bird LB after Leroy Brown . . . For eight weeks I nurtured, fed, and got to know this eaglet . . . releasing LB made me think about life and what it means to be endangered.” When President Clinton evoked the design of the Great Seal of the United States, calling attention to the American bald eagle’s outstretched wings, its olive branch in one claw, thirteen arrows in the other, I instead imagined what LB must have looked like when he smiled. When President Clinton referred to the “proud bald eagle” as a “fitting emblem for our nation,” all I could picture was my grandmother.

The American flag hanging beneath Challenger’s talons made me recall a photograph taken in the aftermath of a 2005 natural disaster. The photograph is of Milvertha Hendricks, eighty-four years old at the time, draped in an American-flag blanket as she waits to evacuate with other Hurricane Katrina survivors. Hendricks’s seated position stands in contrast to the Black woman in flight with a baby in her arms on the cover of Hamilton’s The People Could Fly. White stars and red stripes form the feathers of the huddled wings encasing Hendricks, this beautiful bird of a Black woman. On Hamilton’s cover, a maroon hat covers the Black woman’s head, her face resolutely turned upward. Hendricks stares straight ahead beneath the hood of the blanket cradling her grey hair. I want to superimpose her onto the cover of The People Could Fly. I want her to have the dignity and agency of autonomous flight.

Hendricks’s image continues to circulate widely through the media as a visual representation of the hurricane’s devastation. Rebecca Wanzo’s The Suffering Will Not Be Televised: African American Women and Sentimental Political Storytelling includes the photograph along with the caption: “The tragically ironic and ubiquitous picture of Hurricane Katrina survivor Milvertha Hendricks. Courtesy of AP Images.” Placing the photograph of Hendricks beside the cover illustration of The People Could Fly reminds me of the fine line between pity and pride.

Sarah Vap’s book-length essay End of the Sentimental Journey uncovers the simplistic, sentimental narrative expectations we often bestow upon women writers. As a Black, queer woman I grapple with who has the authorial right or power to be abstract, nuanced, complicated in their meaning-making. I recall entering a Ph.D. program in English literature where my peers were delightedly up to the “challenge” of engaging with James Joyce’s Ulysses while finding Toni Morrison’s Beloved dismissible because of its “difficulty.” Vap points out a reader’s move to accuse a work of literature of being “wrong” or having misbehaved:

Personally, at times like this—when I have read a poem, tried very hard to connect, and failed—I have felt, simply, sad.

But when I hear a poem called difficult—it often seems like the person is saying that the poem, itself, is somehow wrong.

In some cases, difficult sounds like we’re accusing the poem. That the poem has been bad. Difficult.

As if the poem was supposed to give the reader something wonderfully satisfying, and didn’t.

I have heard before that my poetry is too hard to understand, the implication being that I, as a poet, am too difficult. Many times, I have experienced being told I am wrong—Black, woman, queer. The first time I made love with a woman, she broke me open. Pain feathered my back as her red, stiletto-pointed fingernails tore into my skin. Because desire is a hook in the body, I did not have the heart to confess that it hurt. The next morning, staring in my apartment’s full-length mirror, I surveyed the tender damage and applied ointment to the wounds that had made a home of my brave body. What I am trying to say is I want to imagine a more expansive way of reading and being in the world that allows for my mother to perceive a hawk as her mother, and for that reading to be not singularly right but one of a thousand wrong conclusions that is nonetheless valid and true.

The second time I took my mother to meet with the falconer was during the earlier stages of the COVID-19 pandemic. This time, my mother and I were the only participants. The hood, or leather cap, used to cover the head and eyes of the hawk was visually adjacent to the cloth masks that covered my mother’s and my noses and mouths. Taking a nod from Tina M. Campt’s Listening to Images, if you listen to the figure 2 photograph in relation to the figure 6 photograph, how does my covered mouth versus uncovered mouth sound?

“I am leaving you all my journals, but you must promise me you won’t look at them until after I’m gone” is what Terry Tempest Williams’s mother, the matriarch of a large Mormon community in Utah, tells her daughter a week before she dies. It was a shock to Williams to learn that her mother had kept journals, but not as much of a shock as it was to discover that the three shelves of journals were all blank. A replication of empty pages, an archive of silence, is what is reprinted (or unprinted) at the opening of Williams’s poetic memoir When Women Were Birds: Fifty-four Variations on Voice. In line with Williams’s mother, I have left you a clearing: [ ]. If the brackets are two trees, tell me what you see between them.

My mother and I had our intermediate lesson on a January afternoon. That day, the sky was so clear you could hear the wind whisper. This time, instead of Goose, my mother and I interacted with one of the falconer’s other male Harris’s hawks, named Maverick. We got the chance to fly Maverick against the watercolour blue of the Colorado sky. It is far too complex to reduce to language what it feels like to see a hawk dive headfirst, to feel the rhythmic drumming of wing muscle on air. It’s like living many lifetimes all at once. It necessitates difficult details to convey the hawk’s grace as it danced from tree branch to tree branch, returning to our hands to collect scraps of frozen mouse meat. What I learned from the lesson: 1. Memories hunger. 2. There is a cost to keeping them alive. 3. You can’t forget to feed your ghosts.

Prey tell the truth. Before having me, my mother had an abortion. The day she helped me do the same, her nails, like talons, gripped the clinic’s waiting-room chair. The definition of mercy: my mom, an only child, watched me, her eldest of three, like a hawk, as I gave up the ghost inside me. My mother was denied the ability to accompany me into the backroom. I made a sound like the word for yes when asked if I wanted to view the ultrasound. Difficult to detect on the screen, my baby was swaddled in staticky black, hardly the size of a flower bulb nestled in the darkness of the earth. I was sharp, my response clipped. My answer again a yes when the doctor asked for verbal confirmation to proceed.

The last three lines of the third stanza of Robert Duncan’s poem “My Mother Would Be a Falconress” pose a question:

When will she let me bring down the little birds,

pierced from their flight with their necks broken,

their heads like flowers limp from the stem?

I was first introduced to Duncan’s poem by a fellow writer who thought that to equate one’s mother with a raptor must speak of her character in a negative way, a depiction of a parent as a frighteningly fierce figure. While I don’t doubt fear can be a form of love, I did not have the anticipated response of horror to Duncan’s portrayal of a mother. Instead, I gently traced the image of the falconress suspended by words on the blank sky of a page. I know what it means to disown a child not even born and to do so in the fraught hope that to love is not to own but to set a little bird free. I think often of the poet José Olivarez’s lines:

i killed a plant once because i gave

it too much water. lord, i worry

that love is violence.

This is what it means to love, to do things you had never imagined you would do. This is what it means to be a mother, a furious flower—murderous and innocent as water.

Mnemosyne was seduced by shape-shifting Zeus, who took the form, or guise, of a mortal shepherd. The nine Muses are the result of Mnemosyne succumbing to his deception for nine consecutive nights. Greek mythology often obscures the suffering of women. Translation is, after all, a slippery snake. I remember waiting until my ex-husband left for work. I remember my mother and I putting all my belongings that would fit into my car and driving from an extended-stay hotel in Virginia to my mother’s home in Missouri. I remember, on the brink of losing my mind, fleeing the toxic environment of abuse and in so doing losing a child. If you go looking for pity, you will find it. Can you find it in your heart to feel sorry for me, or am I being overly sentimental?

I fondly recall the faint glow of the night light in my childhood bedroom, the soothing sound of my mother’s voice as she read me bedtime stories, the warm sensation that would envelop my small body as “The People Could Fly” came to its close:

The slaves who could not fly told about the people who could fly to their children. When they were free. When they sat close before the fire in the free land, they told it. They did so love firelight and Free-dom, and tellin’.

They say that the children of the ones who could not fly told their children. And now, me, I have told you.

Often, my mother finds me melancholic; she worries about my well-being. It is in moments of anxiety-riddled stress and sadness that she will fortuitously call me or send me a text message out of the blue. She wants to tell me she has just seen Grandma; she wants to let me know this means I am safe.

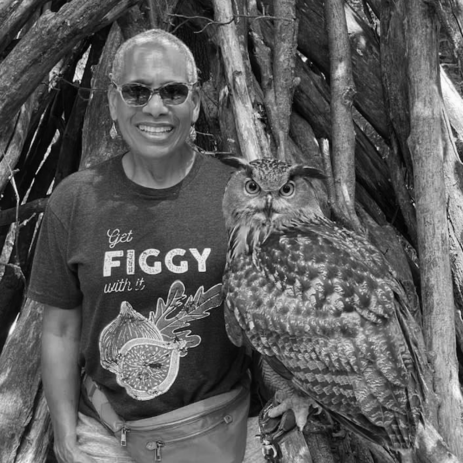

Alison C. Rollins is the author of the poetry collection Library of Small Catastrophes. She is currently an M.F.A. candidate at Brown University. Her work across genres explores the fragile line between “human” and “nonhuman” beings through power storytelling and nuanced forms of representation.