A version of this conversation was broadcast on Writers & Company on CBC Radio One, produced by Sandra Rabinovitch.

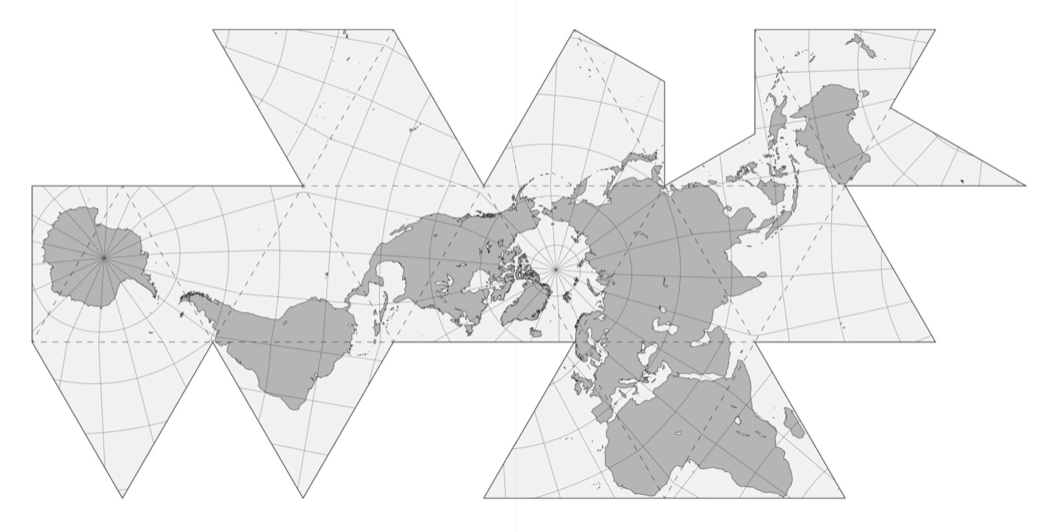

Kei Miller is an original. I first heard of him when his 2014 poetry collection, The Cartographer Tries to Map a Way to Zion, won England’s prestigious Forward Prize for Poetry. The book imagines a dialogue between a map-maker, a rationalist trying to impose order on an unknown land, and a Rastafarian—or Rastaman—who questions his project, offering a different way of understanding the world. The judges praised Miller’s ability to “defy expectations” and “set up oppositions only to undermine them,” commending the book’s “boldness and wit.” The Cartographer was his fourth collection.

Then I discovered that Miller is also a short-story writer, novelist, and essayist who has been winning prizes since he began publishing eight years earlier. And he’s been impressively prolific.

Miller was born in Kingston, Jamaica, just thirty-nine years ago. He studied English at the University of the West Indies and then in Manchester, where he obtained a master’s in creative writing. More recently, he completed a Ph.D. in literature from Glasgow University. Along the way, he was the editor of New Caribbean Poetry: An Anthology and the Heinemann Caribbean Writers Series. He also wrote a book of “essays and prophecies” called Writing Down the Vision.

In 2016, he came out with his third novel, Augustown—vivid and imaginative; drawing on Jamaican history, religion, and politics; and revolving around strikingly memorable characters.

I met Kei Miller at the CBC’s London studio in May 2017.

Eleanor Wachtel: We tend to think of maps as official documents depicting real geographic places and borders, documents that carry some authority, but you say in your collection The Cartographer Tries to Map a Way to Zion that maps are problematic. What do you see when you look at a map?

Kei Miller: I see the things that aren’t there, the things I know are there but were never represented. With this book, I was looking at some early maps of Jamaica, especially eighteenth-century maps of plantations, et cetera, where it will be clearly outlined where a great house was, and I know that all of three people lived in that great house. I know that two hundred yards away is a village that had three hundred people, but the village isn’t on the map. So why is the great house important but the village not important? Maps are always interesting to me for what’s left out, and all those questions of power, how all those things play out on a map, and how they create certain silences. How do we tell these stories that aren’t shown?

Wachtel: As you say in the collection, on this island—Jamaica—things fidget, even history. Landmarks shift, whole places can slip out from your grip. So what does the map-maker need to know?

Miller: That his science isn’t the only way of knowing a place, which isn’t to say that the map-maker’s way of knowing is invalid, just that it misses things. But other ways have their own blind spots. And so every way of knowing this world is incomplete. In one poem I say every language is partial, and I mean that in every sense of the word, that it is incomplete but it’s also biased, and we should know those biases and be alert to them.

Wachtel: The Cartographer Tries to Map a Way to Zion features these two distinct voices: the cartographer, who speaks, as you say, the Queen’s English, and a Rastaman, who uses Creole or patois.

Miller: Yes, though they begin to slip into each other.

Wachtel: You mentioned that when you read from The Cartographer, if you read in England, they assume you’re the Rastaman; if you read in Jamaica, they assume you’re the cartographer.

Miller: Yes because they hear my accent immediately in Jamaica. My accent in Jamaica registers in a different way than it would in England.

Wachtel: And it’s not just how they talk that sets the Rastaman and the cartographer apart; it’s their different ways of seeing the act of cartography and the world. Why did you want to put these two voices in conversation?

Miller: I always want to challenge myself. While writing this book, I had long dreadlocks. And so when the book came out, it was easy for people to think I was the Rastaman in the book, but in my mind I was clearly the cartographer. In my mind I’m clearly questioning myself and questioning the way I was taught, the elite education I was privileged to get: how does my education make me see the world, and how do I challenge myself to see other things? In several books I try to think about the things I know, and how I know them, and why I feel so sure about this knowledge. And so the Rastaman is there to challenge me more than anyone else.

Wachtel: What prevents the cartographer from mapping a way to Zion? What’s he missing?

Miller: First, he thinks it’s a physical place, and so his tools are, just in a very basic sense, not up to the challenge. You can’t use scientific tools to find your way to a place that is in some senses spiritual. And what he’s privileging, cartography, is a Western science and a Western way of knowing the world. He is using the tools of Babylon to find its opposite, and so it’s bound to fail. He’s using ways of knowing that always reduced Black people’s lives. He’s using a measurement called the metre, which erased several measurements indigenous to Africa. He’s using the tools of the map, which is such a major tool of the colonizer. If I want to declare that I own this territory, how do I do that? I draw a map, and in drawing that map, I have created a reality. The cartographer, therefore, using these colonizing tools, is bound not to find Zion from the beginning.

The whole book is interested obviously in maps and cartography and the things that maps miss, but in a larger sense it’s interested in language: what languages were despised or never credited, and what ways of speaking the world were always looked down on. What kind of poetic voices aren’t privileged because other metres, probably the iambic pentameter, delegitimized those ways? When I was an undergrad, a teacher told me that English-language poetry privileges the iambic pentameter because it is the rhythm of the heart: du-dum, du-dum, du-dum. Even then I thought that was crap. I thought, If I get a stethoscope and I listen to my heart, will I really hear perfect iambs beating out? And I wondered then about how we use metaphor to legitimize certain things, and how we place it in the body, and especially how we place it in the place of the heart. Later on I learned that one of the most basic rhythms in Rastafari, the Nyabinghi rhythm, dup-dup, du-du-du-du, dup-dup, that’s also called a heartbeat rhythm, and that was one of the things that started the collection. Here I have the iambic pentameter, which in some ways is seen as the rhythm of the heart, and here is a Rastafari rhythm, which is also called the rhythm of the heart. How could I put these two rhythms together, and what dissonance might happen? And so that’s why you might realize the poems slipping in and out of almost perfect iambic pentameter moments and then slipping into other kinds of rhythms, trying to bring the two together to form a new music.

Wachtel: At one point the cartographer says to the Rastaman, “Every language, even yours, is a partial map of this world.” What’s the relationship suggested here between place and language?

Miller: That place is language. As I said, for the book, knowing places, or mapping and measuring, is always fundamentally a metaphor for language and how we speak. I know the world by how I speak the world. In reading, say, Sam Selvon’s The Lonely Londoners: it’s so profoundly and insistently a West Indian novel. While it uses all the standard ideas about what England is—the fog, the mist, the cold—it fundamentally changes London because it renders London in a new language. London becomes familiar to every West Indian person who reads it because the place changes. The place changes because the language by which we know the place has changed.

Wachtel: In The Cartographer, these questions of maps and history and language are reflected in the place names. Your book includes a series of prose poems on that theme: sometimes the official name of a place is different from what the locals might call it. Can you tell me how that works?

Miller: Well, this happens everywhere in the world just by certain processes, folk etymology especially, even here in London. Elephant and Castle was thought to be named after the visit of a princess from Spain, the Infanta de Castilla. The story goes that the poor English people couldn’t wrap their tongues around Infanta de Castilla so it became Elephant and Castle. The same thing happens in Jamaica. Where we call Shotover—and we give a whole reasoning behind that: there was violence there; shots were fired all over the place in the time of slavery—in truth the name comes from a French-owned villa, Château Vert.

Wachtel: But there are also ones like Me No Sen You No Come.

Miller: One of the things I was interested in is, if you come from a country where people aren’t allowed to read and write for four hundred years, how do they store their history? How did they record the things they knew or the ways they saw the world? And sometimes that happens through place names. Shotover in a way is a mishearing of Château Vert, but they recorded history in that name. They found a way to say, This is what was happening: there was violence in this place and there were lots of shots fired. In the mishearing and the renaming, things are recorded, and if you have the right tools and the right ear and the right sensitivity to unlock these histories, I think you can. Me No Sen You No Come is another.

Wachtel: What does that reflect?

Miller: Well, Me No Sen You No Come: if I don’t send for you, you should not come.

Wachtel: Which could be a profound comment on colonization.

Miller: Absolutely, which is exactly how I see it. There is something so powerful in that name, a moment where Jamaicans suddenly see themselves as belonging to that landscape, having ownership of that landscape, and having the audacity to give and refuse welcome.

Wachtel: Your own spot on the map, the place where you grew up, is Hope Pastures, a middle-class neighbourhood in Kingston. The name sounds pretty bucolic. What was it like there?

Miller: Oh, boring. It was, I think, the life of every suburban child in the world, really. When I was about nine or ten, some kids walked by and threw an egg at my neighbour’s door. The whole neighbourhood was scandalized. The world was coming to an end. So it was that kind of neighbourhood, where that could have been such a big moment. Tells you everything about that world and how it was divorced from some of the bigger things that were happening in Jamaica.

Wachtel: It’s considered part of uptown Jamaica. In other words, it’s a relatively affluent community situated literally up in the hills. Can you talk about the relationship between uptown and downtown Jamaica?

Miller: These are very elastic terms. They do demarcate class, but uptown and downtown—though at some level they refer to actual geographic places—they’re actually quite mobile, and so, on the ground, uptown and downtown communities are often side by side, but you still avoid the places that are downtown, and you drive in various circuitous routes in Jamaica to always be uptown.

Wachtel: Although you’ve tried to hide your uptownness at times.

Miller: I do.

Wachtel: Why, it’s uncool?

Miller: At some moments it can be, but sometimes I do it to kind of mock myself and some of the pretensions I think follow being from that world. In another sense, I actually find it important not to hide it. You know that phrase check your privilege: I do think there’s a lot of privilege uptown Jamaicans enjoy that they never check, particularly if you are a Black Jamaican because then you think that race almost means you don’t enjoy the privileges that you do enjoy. It’s harder for you to check it and harder for you to acknowledge the ways in which you are Babylon and you are an oppressive force.

Wachtel: Is it possible to check your privilege? I know the expression, but I wonder, is it something you can actually do?

Miller: I hope so. I think it is genuinely hard. The thing about privilege is that it never feels like we’re privileged. It feels natural; it feels like the right that everyone should have. There are those dark moments when you realize that other people don’t enjoy the ease of access you enjoy. And of course probably that’s easier for me, having moved from a country where I did live in a fairly middle-class environment, and I still do here, but that assumption isn’t taken for granted. So it’s me being on faculty at a university going to the toilet and the security guard telling me, “I’m sorry, that’s for faculty only.” Or it’s smaller assumptions. It’s someone introducing me and saying, “This is Kei. He’s a poet,” and always it is, “Oh my God, so you’re a slam poet!” Racial assumptions, just casually dealt out. My other friends who are introduced as poets and are taken as poets, they might not recognize the privilege of that. They have just moved in privilege, but it seems casual, to be expected.

Wachtel: It’s so invisible.

Miller: Yes. And so I do think it’s hard. I think probably moving between landscapes it becomes easier.

Wachtel: I’d like to hear more about your family and upbringing in Hope Pastures. You’ve written a lot about your mother. Can you tell me a bit about her, her background, her personality, what she was like?

Miller: Both my mom and dad came from fairly large families, which were similar in some ways but very different in others. I could see an ease of class in my father, who was from an educated middle-class family, and I could see in my mother how class could consciously be performed, because it was important to her to perform class and she did it very well. She could move up and down a language range that was not accessible to my father. My father moved in a very limited register of Jamaican English. My mother’s range of English was much wider, much more interesting.

Wachtel: Well, she was a preacher’s daughter.

Miller: She was.

Wachtel: How do you think that marked her?

Miller: I don’t know. In some ways she probably wasn’t the typical preacher’s daughter, or what you might expect from the typical preacher’s daughter, and I don’t know how to make sense of some of those things. I used to come home from school some days and my mother—she wasn’t above emotional manipulation the way that no mother is above emotional manipulation—she’d be there looking forlorn, playing Scrabble by herself to make us feel guilty so we would play Scrabble with her. My mother and all her sisters are brilliant, ferociously skilful Scrabble players. In a way, words and language, being flexible with language, were more important to my mom and her family, and probably that had something to do with her father being a preacher. It also meant that though they came from rural Jamaica, they were the good family in the district. My grandfather wasn’t only a preacher: he was a political activist, he was the councillor of the area, he was in local government elections, giving all kinds of speeches. They were the family that people looked up to in that community.

Wachtel: But you invoke your mother’s loud voice . . .

Miller: She was a loud woman.

Wachtel: Is that in a good way?

Miller: I don’t know, both. Loudness was a part of who she was. I was terrified of it as a child, but it also meant she was a brilliant reciter of poems by Louise Bennett, a dialect poet who stands in Jamaica’s consciousness as our most national of poets. Everything about my mom was loud and joyful. She could be loud and very angry in other moments.

Wachtel: Maybe that’s why you say you “worked hard to make [your] mother laugh.” What kinds of things did she find funny?

Miller: I think she found human pretension relentlessly funny. It is sad now that there are so many things I see happening in the world that I find so immediately funny, and I think, Oh God, I want to tell my mom this.

Wachtel: She died relatively young, when you were in your early thirties. You wrote a book of poetry that you felt was inspired by her. I was struck by how you wanted to write about hope and even joy after your mother’s death. Where did you find that hope?

Miller: Hopefully somewhere in the middle of writing that book. Joy is important to me, and I think pain makes joy all the more urgent. It’s an important thing to look for and to practise, which absolutely isn’t negating the bad things: it is insisting on joy in the midst of the bad things. And so that book, A Light Song of Light, and perhaps the first movement of that poem, says everything I want to say: “A light song of light is not sung / in the light; what would be the point?”

Wachtel: What about your father? What was he like when you were growing up? What kind of work did he do?

Miller: Oh, he’s me.

Wachtel: He’s you?

Miller: If you see me, you see my father. I am every bit like him.

Wachtel: What does he do?

Miller: He’s retired now. He was a consultant with the government, kind of like my grandfather but behind the scenes; he worked in local government and became the authority on local government. His whole life was therefore “we can’t accept things as they are; we have to think about how to make them different, how to restructure things.” In his job in local government reform, he was always thinking about how you make the government listen to people, how you get the people involved; how do you respect them and how do you listen to their stories? He got so much joy from that and talked about it a lot with us. So naturally he got us very involved. No matter how bored we were, we had to talk this through with him. That shaped us a lot, both me and my sister.

Wachtel: You said that your great-grandmother was disappointed when your father, who’s light-skinned, married a Black woman, that she believed in marrying up or marrying someone with lighter skin. Is that still a common attitude?

Miller: Oh yes. We might not admit to it as much, but Jamaica is, and I know I’ll get in trouble for saying this, Jamaica is a very racist society. And it is very racist because we never use that word, because our racism is so wonderfully sophisticated that we call it classism or shadeism, all kinds of other things. We never get to what’s at the heart of the kinds of discriminations we practise, so it never appears to us as racism. Racism, for Jamaicans, is something that operates in history and in America, not in Jamaica today. But a lot of what we call classism in Jamaica is very much rooted in racial attitudes, and a lot of what we call shadeism is obviously rooted in racist ideologies. Yet we never ever use that word in Jamaica. We pat ourselves on the back and applaud ourselves for being essentially a non-racist society where race doesn’t matter at all, which in my mind is absolutely not true.

Wachtel: Religion was an important part of your early life and your development as a writer, you’ve said. Can you give me a sense of the religious landscape in Jamaica?

Miller: Religion is a big part of the fabric of Jamaican life. When I was younger, it felt to me that there were only different kinds of Christians, but there was no such thing as a non-Christian. When I was teaching in Jamaica very recently, one of my students asked me if I was a Christian or a backslider; the world was divided into these two sets of people. I suddenly remembered that that’s what life is like in Jamaica. Either you’re a Christian or you’ve backslid from being a Christian. I’ve often said that I think it might actually be easier to come out as gay in Jamaica than to come out as an atheist.

Wachtel: Really?

Miller: Oh yes. Again, we came from a household where my sister and I could have discussions with our father, we could negotiate a way not to go to the Anglican church our parents had us go to, but it never felt that the option was to leave church altogether. The option was to choose another church that you thought you might find more appropriate, and so we did, which in its own way was good. It meant that religion, at some point, was our choice. In the end, that gave me the freedom, ever so reluctantly, to leave. But religion did become my own. I was thinking my own way through it, and therefore I could think my own way out of it.

Wachtel: But your way out of it seemed to be via getting deeper into it, because you were even preaching at one point.

Miller: Definitely. Religion was very important to me, and I think it is absolutely part of my spine now, in some of the values I picked up. There’s an effect of the devout, of the almost fanatically religious person, that I cannot mock. I see the beauty of it. And I know these people, I know what is in their heart. I have seen their generosity; I’ve also seen how cruel they can be. But religion gave me a pair of eyes. It shaped who I was as a writer in fundamental ways. Listening to preachers, I was learning sophisticated lessons about writing, things as important as how to place and use a verb, why the verb must enact something different in the noun: it must give to the noun a possibility that that noun didn’t have before. And I knew from listening at church, even if the pastor wasn’t aware, that it was because he applied a strange verb to the noun, that’s what made the congregation shiver, that’s what made them shout, “Amen,” that’s what made Sister Gilzene throw up her hands in the back and shout, “Hallelujah.” I knew she was responding to language. And so, to me, it was a fundamental lesson about how to manipulate language. It gave me technical skills that I probably would have picked up eventually, but I picked them up in the church.

Wachtel: And how did preaching get you out of the church? When you were eighteen, you were asked to give a series of sermons at a Pentecostal summer camp, and the sermons were a success. And yet it was the start of a gradual pulling away from the church.

Miller: I felt like a fraud. People would come up to me, very complimentary, and say, “God was moving through you.” And I thought, No, that was the verbs. The verbs did that. At some point, I knew how to write and deliver a good sermon, but I also knew that what I was interested in was the artistry of language and how language could move people; I wasn’t interested in the supposed Holy Spirit behind it. And it just made me feel like a bad person to receive compliments because of that. But other than forming who I am as a writer, church also formed who I am as an intellect, and that doesn’t make sense to a lot of people. The church I went to was adamant that you worship God with all your heart and all your soul, and they would rattle through these two, but for them it was also important that you worshipped God with all of your mind. They actually gave us tools that not many churches would give. They said, “Even if we give a sermon, don’t trust it. You need to be curious and test it with your own intellect.” They taught us how to be curious, and in a sense they also taught us how to leave. And I can’t not be grateful to them for giving me the tools that allowed me to do that.

Wachtel: It’s extraordinary that that would be part of the import of the religion. Did you feel a sense of loss when you left?

Miller: Oh, I still feel a sense of loss, yes. A deep, deep sense of loss.

Wachtel: It’s irretrievable?

Miller: I try to retrieve it. I try to go back, and I try to feel what I used to. I am jealous of people who don’t have the filters going through their brains. I guess my politics just became more developed—and again, it’s politics that started in the church, about how you think about the outcast, how you think about privilege, how you use language toward them—and eventually I saw how hurtful the church could be, how it mobilized its position of strength in Jamaica in really problematic ways, in really unloving ways. And I cannot un-see that.

Wachtel: What are you thinking of in particular?

Miller: I’m thinking of a few things. Obviously I’m thinking about sexuality, about how the church treats LGBT people. But there are other things. I remember taking a Syrian friend to a church once, and it was this wonderful sermon about how God moves us from places of comfort to other places and how He will see us through. And the preacher chooses to read this passage where God, taking the Israelites out of the forty years of wandering, decides to smite all the Hittites, and it’s a passage that is basically sanctioning genocide. These are all of my friend’s people. And as the preacher calls out these names, the church is responding to this as just a metaphor. They’re shouting, “Amen,” and my friend breaks down crying. I am horrified by this moment, horrified by what they’re saying and what they can’t hear that they’re saying. And even if I said, “This is what you just did,” they’d be like, “No, but it’s in the Bible.” And certainly the Bible, in that moment, wasn’t just a book of metaphors. It was sanctioning things that are happening in the world right now that I fundamentally couldn’t approve of.

Wachtel: In the opening of your latest novel, Augustown, you invite us to imagine ourselves up in space gazing down at the Caribbean, and you give us the geographic coordinates for a dusty town in a ramshackle valley on the island of Jamaica. Tell me about this place, Augustown, and why you want to take us there.

Miller: I don’t admit it in the beginning of the book, but the house I grew up in, in Hope Pastures, looks down on the real August Town. In the book, there is one small dishonesty, where it’s the houses of Beverly Hills that look over Augustown, but that’s not completely true. The houses of Beverly Hills are above August Town, but they kind of turn their back to it, and so they would look down generally in another direction.

Wachtel: So Beverly Hills is another neighbourhood in uptown Jamaica?

Miller: Yes. But I was really putting myself back at my house and thinking about what that meant. Why do middle-class people in Jamaica move up to the hills? What attracts them to the hills, and what does that position mean, to not metaphorically but literally look down on people? So the book, for me, has to start from that position of looking down, and hopefully complicating that throughout. But why August Town? Because it was the place I always looked down to. It was a place I could always hear. I could always hear the music coming from it. I could always hear the guns firing there. It was a dangerous place; it was the closest downtown to us.

Wachtel: You talked about place names, but what’s the background to this one?

Miller: So August Town, named after August morning, the first of August 1838, the day of freedom.

Wachtel: When slavery was banished in the British Empire.

Miller: Yes. You have to imagine people walking off an estate and coming to this new plot of land, this new place of freedom, and naming it after this freedom as if it was something achieved. The village becomes the embodiment of their freedom, and in a way you wonder, Was that true? The name symbolizes a kind of hope, but when you grow up years later, you’re hearing gunshots from a place named after freedom, and you’re hearing sirens rushing toward a place of freedom. You think of people who grew up in August Town, some of them feeling trapped and August Town being a place they need to escape from. What a turnaround is that, that August Town was the place they escaped to years ago, but now it’s a place people escape from? How do you tell that story?

Wachtel: The real-life figure at the centre of the story is the preacher and church leader Alexander Bedward, who told his followers that he was able to rise, to levitate. He would ascend to heaven on December 31, 1920. Can you tell me a bit more about who he was and what he represents to Jamaicans?

Miller: I can tell you what he represents to Jamaica: he represents the idiot. He represents the absolute imbecile. You know: what a fool, he thought he could fly. That’s how the story was always given to me. I don’t think he represented that to his people at the time. In 1920, Bedward tells his followers that he’s going to fly to heaven, gather bolts of lightning in his hand, come back, and smite all white people. The white people in Jamaica are not very pleased by this, not that they think he’s going to actually fly, but there are too many of the ingredients of a revolution happening: a preacher who is so widely popular across Jamaica, even across the Caribbean, that when he gives this prophecy, people come back to Jamaica to see it happen. Imagine so many people, Black people, so many folk people who are losing their jobs for one reason or another, all gathered in one spot, all communing and thinking about their mutual oppression. It’s too much of a recipe for something nasty to happen. At the same time, in the background is Marcus Garvey, stirring up an intellectual Black consciousness. There’s intellectual Black consciousness being stirred up by Marcus Garvey, and there’s spiritual Black consciousness being stirred up by Alexander Bedward, and these two things will meet; they will come together and become Rastafari. Everyone tells the story of Marcus Garvey and Rastafari, but no one tells the story of Bedward and Rastafari, and he is the other half of the equation.

Wachtel: And you said you were told by God to write about Bedward in a dream. Is that true?

Miller: No, I was making a little joke. I woke up one night and a voice of a certain distinction and age and gravitas said to me, “It is time to write about Bedward.” But that really was just a memory because it was the voice of Kamau Brathwaite. I’d been to one of his lectures where he’d broken from his notes and said, “It’s time to write about Bedward.” And so, probably fifteen years later, I was dreaming that moment again.

Wachtel: Because I was wondering, given that, as you say, you grew up believing that Bedward was an idiot, how you came to want to rehabilitate him, in a certain way.

Miller: It came from that process of distrusting myself, distrusting how I know things, distrusting the class that I am from. I was reading accounts of the time, reading the accounts of Bedwardites, and feeling that there’s a different story there. I also read accounts about Bedward written by the middle class, and it was impossible not to see the rampant mockery and classism and racism in their accounts. Why did they need to tear him down like that? What was so threatening about him? Those things begin to tell you there is another story here, there is something else that people have missed. And I guess I am the kind of person who now becomes attracted to those untold stories. The official account is going to miss something, and maybe I can tell it.

Wachtel: In your novel, Bedward’s story is told primarily from the perspective of Ma Taffy, this old Rastafarian woman who was present on that day in 1920 when the preacher claimed he could ascend to heaven. Ma Taffy has lost her sight, but she’s able to see a great deal. What’s her place in the community?

Miller: Ma Taffy was a strange character for me to build. I learned about her sentence by sentence. The first sentence, I think—“Blind people hear and taste and smell what other people cannot”—I didn’t know before that that she was blind. Until I got to the scene of how she became blind, I didn’t know how she became blind. But I knew I had to mess up stereotypes of the wise old woman very early on. So she had to be on her veranda smoking ganja. Very early on, she has to help Soft-Paw murder someone. And therefore, she’s complicated. She’s not wise and completely innocent in the way that we might imagine. She has a very relaxed morality in some ways. I wanted to resist certain easy ideas about the old woman in the community. People probably respect her, but she doesn’t see herself or act as a community leader. She thinks about her niece and her great-nephew, who are like daughter and grandson to her, and that’s where her allegiances lie. She has sympathy for what’s happening in Augustown; she has sympathy for Soft-Paw and the violence. But she doesn’t set herself up or place herself in the centre of the community in any easy or overly romantic way.

Wachtel: She tells—we’ll call him her grandson, Kaia—she tells him the story of the flying preacherman, and as she’s telling it she smells a new calamity in the air, an autoclaps, to use the term that’s repeated in the novel. Tell me about autoclaps.

Miller: When you hear autoclaps in Jamaica, it’s a very common phrase signalling some kind of calamity that’s about to happen, or sometimes even minor things. But my whole life in Jamaica, every Jamaican will tell you that autoclaps comes from the word apocalypse, which makes complete sense, and it’s not true.

Wachtel: It’s not?

Miller: No, and I was fascinated by this. Friends who are linguists said, No, it comes from a German word achterklap, something bad that happens after an event was seen to have been closed. It was a word used in plantation times in Jamaica, and then everything makes sense about it because it’s very common in Jamaica that the word after would become auto, and so the autoclap, the autoclaps. But even though it may not have come from apocalypse, it does take on so many of those resonances.

Wachtel: So it starts with an interest in a word and its source, but then you create this drama, and the autoclaps that actually occurs in the novel is triggered by Ma Taffy’s grandson’s schoolteacher, who violently cuts off the boy’s dreadlocks. Can you talk about the significance of dreadlocks?

Miller: A part of Rastafari religion centres around the Nazarite vow, which expressly forbids the cutting of one’s dreadlocks. The easy example in the Bible is Samson: you cut off his locks, you cut off his strength. And so Rastafari adherents take this vow, and it is something sacred. I should tell you that the seed of that story in the novel is absolutely true. It’s the story of a very good friend of mine who is a poet, Ishion Hutchinson. But it’s a story I’ve heard several times in Jamaica. What does that mean when a teacher does that?

Wachtel: Because his teacher’s Black. I mean, it’s not a question of . . .

Miller: This is what I talked about earlier, that racism operates in Jamaica in ways that are so perfectly disguised to us, and so a Jamaican might say, “Well, the teacher is Black; he can’t be racist.” But what ideas of neatness are in his mind? What ideas of grooming? He’s affecting something, and race lies at the heart of that. In every teacher who cuts off someone’s dreadlocks, there is a deep anxiety about race and a deep resentment about race and about things that don’t look appropriate. What is at the heart of this scene is that this teacher, who is a teacher I think every Jamaican would recognize, is anxious about his Blackness.

Wachtel: He’s anxious about everything.

Miller: Oh yeah, his Blackness, his sexuality. He’s just a man who fundamentally does not know himself. It’s a real tragedy.

Wachtel: But familiar. You say, every Jamaican would recognize somebody like that.

Miller: Of all the characters in the book, Mr. Saint-Josephs, the teacher, is the one I’ve gotten the most emails and correspondence about, saying, “I know who that is.” And I go, “No, no, no.” “Yeah, I know that teacher you’re talking about.” And I’m like: “No, no.” So he’s the one who is most recognized by Jamaican readers.

Wachtel: Now, you’re not Rastafarian, but you used to wear dreads. How did it affect how you were treated?

Miller: This is one of the things I was interested in, how middle-class people often aren’t aware of their privilege. Locks didn’t mean the same thing by the time I wore them because by then it was a suitable style for the Black intellectual to wear. If we’re talking about the beginning of words, dreadlocks, that word, was very important. They were supposed to be dreadful. They were supposed to look nasty and unkempt. Middle-class people were supposed to look on them and feel dread in their hearts. Now, people go to the hairdresser’s to groom their dreadlocks and to neaten them and to cut them and to trim them. That’s so against the spirit of having hair just growing in any direction and clumping in whatever way and standing as an absolute affront to your ideas of neatness. I didn’t have dreadlocks like that; it was absolutely the tamed lion locks that I had. I had all kinds of middle-class Jamaican friends, Black intellectuals, who were sporting their dreadlocks and felt so proud of themselves that they were standing against a system. But they were standing against a system in a way that had become so clichéd and accepted.

Wachtel: Fashionable.

Miller: Yes, fundamentally fashionable. I wore them for a long time, but I was under no illusion that I was doing anything remotely radical.

Wachtel: Despite her blindness, Ma Taffy can sense that without his dreadlocks, Kaia has become smaller, that he’s lost something that will never grow back. What’s she referring to?

Miller: To have that kind of violation, to feel at that age that you are not safe in your own body, I think that does take something away from a child, some sense of security that a child should have. At the moment when Kaia’s dreadlocks are cut off, he comes to the knowledge that he doesn’t live in a world where his body is safe. He lives in a body that is at risk, and it must be hard to come to that knowledge. At the same time, weirdly enough, he lives in a body that is privileged, because he is mixed-race. The cutting of his locks brings two things at once: on one hand, his body is unsafe; but on the other hand, he will come to recognize the privilege of his body because the cutting of the locks almost shears away the Blackness from him. The reality of his mixed-raceness, of his Brownness, will become all the more apparent.

Wachtel: Augustown is your first novel set entirely in Jamaica, though you’ve been living for some time now in the U.K., currently in London, and before that in Glasgow. I know you visit frequently and you were teaching there recently. How has your perspective on Jamaica changed now that you’re living away from the Caribbean?

Miller: I never know how to answer that question completely. Generally, I resist any narrative that says distance made me see more clearly. I think that’s what diasporic people say to make themselves feel better. The truth is, I don’t know. My way of seeing Jamaica has developed over time, but I can’t compare it to what would have developed if I was living in Jamaica. I do know that the constant going back is important to me, and the constant writing about it and engaging with it. That sense of being on the ground and being always a part of the conversation is important to me. And so I feel almost certain that I see Jamaica better now than I did years ago, but that’s not because of distance actually. That’s because of me forcing myself to be close to it, forcing myself to go back two, three times a year, forcing myself to read the newspaper every morning, forcing myself to have public conversations with the politicians, to always be speaking with the activists on the ground. I’m engaging in a way I wouldn’t have if I was there constantly because I’d just feel, well, I’m there, so I’m therefore a part of the conversation and a part of what’s going on. And that’s not always true.

Wachtel: What would your map of Jamaica look like? Or is that what you’re drawing? I read somewhere that you’re writing about your family and your earlier experiences. Are you constantly drawing your own map?

Miller: That is such a lovely question. Partly I wonder if that’s what my books become. I say again that my books are interested in the bits that are not shown on maps or the stories that haven’t been told, and I think my books try to stand in those silences, those erasures. Hopefully my books begin to be that map of Jamaica. But that’s why I feel I have so many more books to write, because it certainly isn’t finished yet.

Eleanor Wachtel is the host and co-founder of CBC Radio’s Writers & Company, now in its twenty-seventh season. She has also published five books of interviews, most recently The Best of Writers & Company (Biblioasis).