A version of this conversation was broadcast on “Wachtel on the Arts” on Ideas on CBC Radio One in November 2016, produced by Sascha Hastings.

Ai Weiwei has been called the most powerful artist in the world, the most important artist working today, and an icon of resistance. He has reached an almost unprecedented level of international fame for an artist, as much for his status as a prominent critic of China’s authoritarian regime as for his own powerful work, which blends Chinese history and craft with politics and the formal language of contemporary art. His 2010 exhibition Sunflower Seeds filled the Tate Modern’s massive Turbine Hall with a hundred million handcrafted porcelain sunflower seeds. The seeds referred to both the Cultural Revolution, when official propaganda depicted Mao as the sun and the Chinese people as sunflowers turning toward him, and the current “Made in China” phenomenon. It also invites viewers to consider the relationship between the individual and the masses. As the New York Times put it, “the profound resonance, hinged on an axis of sameness and difference, was stark, beautiful, haunting.” Another work, Snake Ceiling, shows hundreds of children’s knapsacks woven together in the shape of a coiled snake and attached to the gallery ceiling. It’s a response to the 2008 Sichuan earthquake that killed almost ninety thousand people, including more than five thousand children, who died when their shoddily built schools collapsed. Ai took the unprecedented step of challenging the government’s official mortality reports, which vastly understated the number of schoolchildren who had died. Together with volunteers he’d gathered through the internet, Ai went town to town and door to door in Sichuan talking to the families of the children who had been killed. Then he published the children’s names, birthdays, and other information on his website. That’s what ultimately led to his arrest and detention. First, in 2011, the government bulldozed his art studio in Shanghai. Then he was detained without clear charges for eighty-one days. He was held in a tiny cell with two uniformed prison guards standing over him at all times. His family didn’t know where he was.

After he was released from prison, Ai Weiwei was under a sort of house arrest. The government didn’t return his passport for another four years, not until July 2015, and his home studio in Beijing is still surrounded by surveillance cameras. But throughout it all, Ai persevered and continued to create new art. He had major exhibitions around the world, including at the Art Gallery of Ontario in Toronto. And coinciding with his ability to travel was an extensive retrospective, as well as new work, at London’s Royal Academy of Arts.

One of the first things he did when he was free was to demonstrate in solidarity with migrants and refugees, both in London and Berlin, where he went to join his partner and young son. Preoccupied with the refugee crisis, he visited more than twenty camps all over Europe, Africa, and the Middle East, and his recently released documentary film, Human Flow, is the result of that work. Amnesty International awarded him the Ambassador of Conscience Award, and in September 2017 he was the recipient of the Adrienne Clarkson Prize for Global Citizenship. In November 2016, Ai Weiwei was in New York for the opening of several new solo exhibitions, and that’s where I was able to catch up with him. He remains as vocal a critic as ever of the Chinese government, and when we spoke, he was dividing his time between Berlin and Beijing, a place that, while difficult for him to live in, feeds him as an artist. Since then, he has concluded that going back to China is too dangerous for him.

Eleanor Wachtel: You were born in Beijing in 1957, and you were about one year old when your father was declared an enemy of the people—he was a famous poet—and your family was sent to a labour camp. Can you tell me a little more about him?

Ai Weiwei: My father was a poet, but he studied as an artist in Paris in the 1930s. When he came back, he was put in jail for three years by the Guomindang. It was then he became a poet. A Guomindang jail was not as bad as today’s Communist jail: you could still write poetry, and there were still magazines that could publish it. So by the time he came out of jail, he’d already become a famous poet. Today, it’s unthinkable. If Communists catch anybody like me, I don’t even know where I am, I don’t know where I can find a lawyer, I cannot even talk to my family. It’s not possible. And don’t even think about writing poetry. You cannot write a word to take out. Completely inhuman conditions.

In 1958, my father was exiled and criticized and sent to labour camps for reform, and the hardest job he had was to clean the public toilets. There were thirteen of them, and it was very, very rough in the farming area, very remote in the Gobi Desert area. And as a poet, as an artist, he worked so hard at first, and it was very impressive. He made those toilets very clean, and I think that the only rewarding feeling he could get was to make the toilets so completely clean. That act influenced me a lot. I think I’m a product of displacement. We were always being pushed by ideology and political conditions. So, you know, I was born radical, I did not become radical.

Wachtel: You and your mother and your older brother, you also went with your father to the labour camp, is that right?

Ai: Yeah, I grew up with them. Most hard labourers are not allowed to raise families in the camp—I don’t know if being able to was a privilege or a punishment—but I don’t think I really missed him that much. I stayed away for two years because the situation was too harsh and they let my aunt take care of me, but the rest of the time we were together.

Wachtel: What do you remember of that time?

Ai: I don’t really remember that much. As a child, you only remember, kind of . . . It’s the Gobi Desert, you know, there’s nothing, not even grass, there’s not much there. But we did have very big watermelons, very beautiful watermelons. Probably the best. I never had a similar experience or the same taste of watermelon afterwards.

Wachtel: And your mother, I understand she was reprimanded for stealing the food of cows that she was caring for.

Ai: That time was very strange. They let her feed the cows because they thought if they let the cows be fed by the other farmers, they would steal.

Wachtel: They would steal the food for the cows because they were so poor.

Ai: There was nothing to eat. And it was corn. But even still, my mom fed those cows, and she had to wake up in the middle of night—cows have to eat at nighttime—but there were rumours that our family was really stealing those cows’ food.

Wachtel: I understand your father wasn’t allowed to write during those years, unlike his time in prison two decades before. Was he able to transmit his sense of language or poetry to you in other ways?

Ai: No, there was no way he could write down anything or be showing any sign of refusing to change himself, to not obey the punishment. That would be a big deal, so he couldn’t write anything. And even if he could write, I mean, to whom would he write? There was no way to publish, and there was no way anybody would appreciate any kind of writing done by him.

Wachtel: Do you remember conversations with him?

Ai: Oh yeah, I remember a lot.

Wachtel: What do you most remember of something he said to you?

Ai: Before he passed away, he said to just live well and don’t try to . . . don’t think that history will remember anything.

Wachtel: Live well and don’t think history will remember anything. I mean, live well, I understand. Do you think he’s right that no one will remember you?

Ai: I don’t think anybody will, and I don’t even think it’s relevant. It doesn’t matter. What’s most important is you can sense you have lived, and you feel pain, and you have the desire to communicate, and you share some knowledge, or you ask some questions only because you have curiosity and you want to know more. And then you wait for the last moment to come.

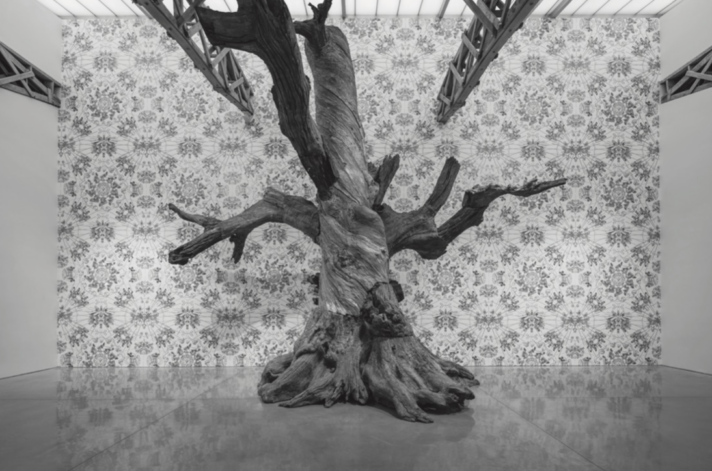

Wachtel: In this exhibit that you have in these galleries in New York, you have several life-sized sculptures of trees and roots made of iron or wood. Some are upright, some just lie on the gallery floor. What do these represent for you?

Ai: They represent a sign of life, life already taken away or surpassed and cast into another material. They’ve been showing in Chelsea, the gallery area, or dealt by commercial dealers to someone who maybe thinks it’s a good idea to collect, but there’s no need to have these. I would not collect these things, you know. There are much lighter, easier, happier things you can collect.

Wachtel: One of the pieces you’ve made is a twenty-five-foot-high tree made of weathered sections of dead trees bolted together in the form of a new tree with spreading branches, and there were a group of these I remember seeing last year at the Royal Academy in London as well, these kinds of trees, and the wood is gathered from the mountains of China. On the one hand, it seems to represent culturally diverse people from all over the country coming together to create a new society, you know, One China, this kind of hybrid. At the same time, it’s stark and it’s without leaves. Do you see it as a sign of hope or of despair?

Ai: I think it’s not a sign of hope but rather a sign of hopelessness. Those trees had been growing for hundreds of years and each had its own life: wind, rain, sunshine created these very unique shapes, but they all died. Most trees in China have been cut down because of population, because of policy, because there is very little consciousness about the environment. So I found those trunks—it’s quite unique actually because I still ask people to look for them and they can’t find one trunk anymore.

Wachtel: Really?

Ai: Oh yeah, in the whole of China, maybe in northern China most precisely, you cannot find one big tree. They’ve all been cut down. When I was two years old, China had a policy that in five to ten years they would catch up with the U.S. and Britain. It was a Communist policy. So how did they measure it? They measured the production of iron. Where did they get iron, how did they make iron? They asked people to burn their iron woks—

Wachtel: The wok they used to cook.

Ai: Yeah. They gave it to the village head, and the village head gave it to the city, and they melted them down. So then how do they eat? They ate in the communes, so they only needed one big wok to cook for everybody. That’s the kind of time we lived in. And today, I use iron to cast those trees. It’s very ironic.

Wachtel: And when you put them together, there are some that are like a tree and with others there’s just a root lying on the gallery floor. Is it just what piece of wood you get? What do you have in mind when you’re creating them?

Ai: Traditionally, it’s not really creating. I do not add anything. The only thing I add is maybe appreciation of doing some effort, of casting it. In China, for scholars to look at those branches or trees or rocks or whatever comes out of nature, which creates very strange forms, I always see that mental study as a part of nature too.

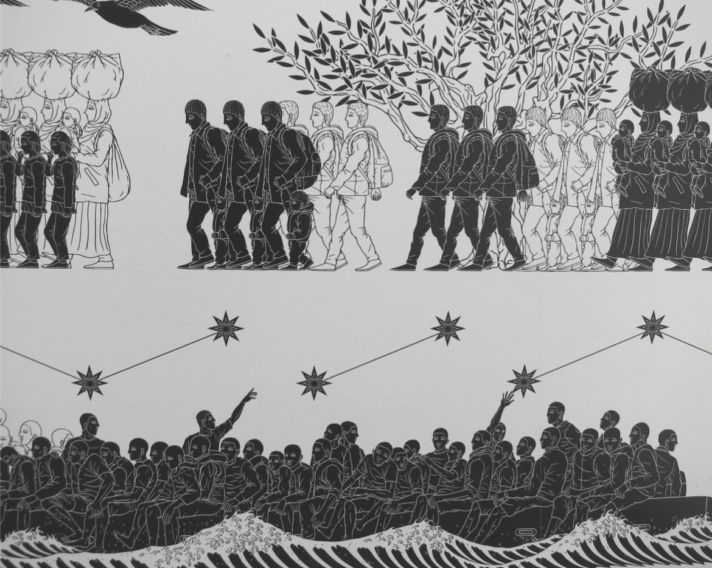

Wachtel: In another exhibition, you fill the gallery with personal belongings left behind by migrants who were forced to evacuate a refugee camp in Greece last spring. You visited the camp. What was that like for you?

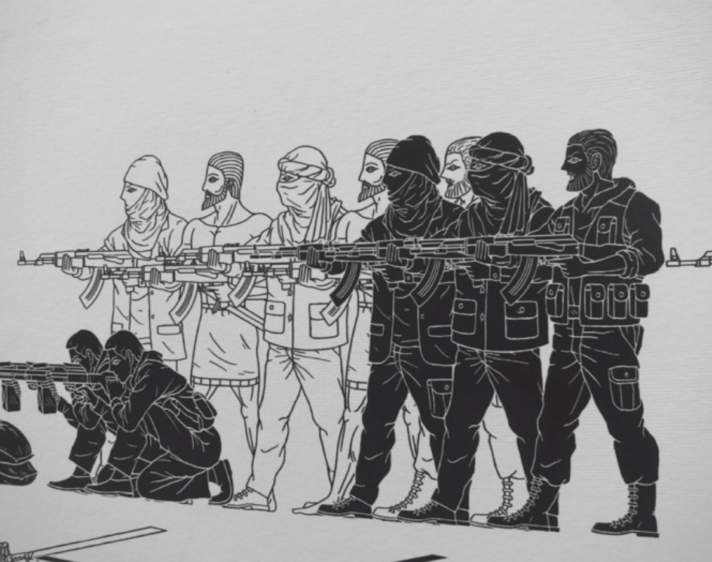

Ai: It’s like if you visit a hospital, only it’s a hospital with no doctors or nurses, and it’s full of patients. They come from war, and they’re scared. They do have a little help, but Europe, which obviously abandons them, puts them in detention. I would call it detention; they call it camps. But for years the refugees will not get a clear answer about how they would get a job or make some money for their children, bring back some food, you know. They get sandwiches, yes, but most of the camps don’t even have electricity. I’ve seen so many that don’t even have light. Basically, they’re neglected. They don’t have identity. Many nations don’t even give them refugee status. They come, then if the war ends, they go back. And they’re not residents, they’re not citizens, they’re not even refugees because refugees still have refugee rights. They’re nothing. So what do you expect? If you have any feeling, you’re too sentimental. This is the world. It’s raining. Everybody’s wet.

Wachtel: But your response is to do something—

Ai: My response is very simple: I want to learn who they are and why they have become refugees. Where do they come from, what’s the problem, who forced them out, for what reason, why can’t the war stop, who’s interested, who’s fighting, where’s the money coming from, who provides the weapons? Then you get a more clear picture: in whose interest is it to have the war, and who’s sacrificed, and why can it not be stopped? How long does the human pain have to last, and who’s allowing this to happen? It’s very clear.

Wachtel: Those are big questions. But in making the art, you focus on gathering and cleaning personal belongings . . .

Ai: Yes. As an artist it’s like, how do you practise, how do you find a language that can make yourself understand and make the people you care about understand? Those clothes that come from Syria: when people leave their homes, they have to grab some clothes for their children, and maybe grab a passport or a key. Then during this long journey, over mountains or oceans, they’re getting so dirty and there’s no place to wash. It’s just not acceptable. So I looked at those things people had to throw away when they were being forced out of the Idomeni camp, and I said, “Ah, that garbage can be cleaned, so maybe I’d like to clean it, piece by piece. Register it.” If I have a chance to have a show, I will present them. You know, as an artist sometimes you get people asking you to do a show, so you’re often asked why you have to do this show, so this for me is a reason. To ask the same question. I don’t have the answer.

Wachtel: But such care with the clothes and the shoes, in some cases cleaning and ironing before displaying the objects. What did you want to communicate by focusing on the objects themselves?

Ai: Those things relate to everybody. A pair of shoes. Or I’ll iron up those clothes, hang them up, and put some family photos on the wall. Being put in gallery condition and making a lot of them. Then the story behind them. I don’t think I achieve anything. They’re just taking up this volume of this gallery space for months. Then it’s over.

Wachtel: When you were in the camp, you invited a twenty-four-year-old Syrian woman to play a white piano that you had brought to the camp. What was that about?

Ai: Camp life is so desperate: people waiting for the sun to come up and then waiting for the sun to go down, and very often the sun never comes up because it can be raining for days. They’re staying in the water. Also, you see a few hundred reporters there. It’s so impossible to make them anything—impossible to help them even. How many hot teas can you bring to them? How many sandwiches do you think you can make them? I heard about a lady who can play piano, and I thought, Oh, that lady, if she’s professional, I really want to bring her a piano so for one moment I can change this feeling, you know. We’re human. We all have a higher sense of what music and art is about. People are not just sitting there to be pitiful. So I asked her, “Do you think if it’s possible I could bring you a piano,” it came out like that exactly. She said, “Oh, I haven’t played for years, but I love piano.” I said, “What do you want to play?” She thought, then she said, “Beethoven’s 7th.” I was shocked. This lady from Syria playing Beethoven? I said, “I’ll get you a piano. Just wait.” I promised her, but I didn’t know how difficult it would be to get a piano to Idomeni. I called all the people I could, a lot of musicians, museums, yet it was too-short notice, too expensive, or the company we were trying to rent from found out we were going to put the piano outside in a camp—I mean, it could be ruined—but we were lucky, and, through a friend, we could bring a piano from Asini, another city. They left at six o’clock in the morning, and by two o’clock the piano arrived. A white piano. And she started to practise. Then it started to rain, so we had to hold up this plastic. I said, “Play anything you can.” It shocked me: she touched the piano, she looked at her hands, and she said, “I’m so sorry, I forget. I even forgot the piano has these black . . . ”

Wachtel: Black keys, yeah.

Ai: Yeah, the half-tones, and I couldn’t even believe it. She said, “I totally forget, because after so many years of bombing I just don’t know how to play.” I thought that must be a joke, I said just play anything. She started, and you could see she knew how to play, she played one phrase, then another. I said, “Maybe just repeat one phrase,” just like a child, to play the simple, to practise some. It’s more as a ceremony. It’s more as a ritual. It’s nothing to be celebrated.

Wachtel: You’re quoted as saying that this gesture “tells the world that art will overcome war.” Do you really believe that?

Ai: I think art is what’s in our heart for peace. I think that will overcome the war because the war is hurting life. There’s no result from that except death and darkness and pain. But there’s always war. That’s why you always need art.

Wachtel: In 1976, after the death of Mao, your father was considered rehabilitated and the family moved to Beijing soon after. What kind of place was the city back then?

Ai: 1976 in Beijing was still like North Korea today—very limited material life, very restricted political situation—but it was a bit better because with Chairman Mao’s death there was a sense of loosening, not so severe anymore. It was kind of like a gap. So I started to study art.

Wachtel: You went to the Beijing Film Academy to study animation. At the time, did you believe that art could effect social change?

Ai: No. I studied everything for myself. It was selfish. I was trying to escape the political situation because art has its own rules and its own logic, so that was a place I could escape to. I hid myself in art. Ironically, later I began being called a political artist.

Wachtel: But then you were involved with a group called the Stars.

Ai: At that time, I was kind of avant-garde because that was the only group that didn’t belong to the Communists. We organized our own shows, and of course we were being crashed by police, and later they let us show again. It was like a gesture, a kind of liberal gesture.

Wachtel: In 1981, you left China for the United States. Why?

Ai: Escape. I just wanted to escape, just like all those people wanted to escape from the war, and I escaped from this political dialogue, this very, very harsh situation I experienced, and I think I needed direction. Outside of China I would go.

Wachtel: Apparently you told your mother that moving to America was like going home. Why?

Ai: I don’t know what I was saying. My mom was so worried that I had no money and I didn’t know English. She was worried, so I said, “I’m going home.” That shows how determined I was to stay anywhere else but China.

Wachtel: What were your impressions of New York?

Ai: Then or now?

Wachtel: Then.

Ai: I sensed first a liberty. Suddenly nobody cared who you are or paid attention to you. You’re someone who has to survive on your own. It’s a kind of release, but very soon you realize it’s a very lonely city. It’s not really a city for poor people seeking opportunities and surviving in this fortress-like forest.

Wachtel: How did you survive?

Ai: I’d do anything possible to survive, just like anybody on the street. I found any job I could do, just to feed myself.

Wachtel: You were a street artist, and you were also a gambler. Apparently you played blackjack.

Ai: I was a street artist, and I worked in a shop. By the weekend the owner would look at me, I’d look at him, and I’d know what was in his mind, and I’d say, “Should we go?” He’d say, “Yes.” Then we’d get in his car, he would drive to Atlantic City, and we would play at Trump’s casino, and sometimes I’d win a little bit, sometimes I’d lose a little bit. I was not a serious gambler, but that moment, sitting in front of a casino table, makes you understand more about capitalism. There’s you, this game, and this money, and you manage not to be completely wiped out. As long as you have a stack or some chips, you can still make it. But if you’re completely wiped out, that’s the end of it. Nobody’s going to help you.

Wachtel: In New York you were exposed to modern and contemporary Western art for the first time, especially Marcel Duchamp and Andy Warhol. How did they shape you as an artist?

Ai: Well, in New York, you see everything everywhere, and you have to just make your own judgment. It’s like a market and they have one hundred types of toothbrush or a lot of toothpaste, but you only pick up the one you think is more fitting to your situation. That was my thing, that was my condition: I came here and I have to make choices. I will see what will be possible, and what’s more interesting, what’s more intelligent, and what seems not relevant.

Wachtel: In 1993, you returned to Beijing because your father was ill, and this was post–Tiananmen Square. How had the city and its art scene changed since you’d left twelve years earlier?

Ai: Nothing really changed. The city looked like it had changed, maybe you’d see another bigger road or more buildings, but to this day the control of the Communists has not changed. There’s no freedom of expression. After sixty years they don’t trust their people. There’s no independent media, radio, or television, and not a single newspaper that doesn’t have to repeat the Communist line. And there’s no independent judicial system. Think about that. So what would be the effect on a public life or an individual life? If all those have been taken away, who are you? Can you still consider yourself a person or a citizen? You’re nothing.

Wachtel: But making art in that context, I mean, one of the pieces you did—

Ai: I never wanted to make art even then because in that system you cannot freely express yourself. Who’s going to show your work? To whom are you going to show? I did a few silly pieces just to charm myself and my friends, but I never thought I would have a show, which is a fact: I never had a show until right before I moved away in 2015. I did try, and they allowed me to do it. But before that, I didn’t even try. I didn’t like to make art in a nation that has strong censorship.

Wachtel: But one of your most famous pieces from this time is a photo triptych that documents a performance you did called Dropping a Han Dynasty Urn.

Ai: I did that as a joke, you know. It’s nothing important. It’s not relevant. I just did it. I happened to have a camera, and this vase was there. I paid for it myself, and it stayed in my home for quite a while, and I guess I got bored of it. And even that piece, which I did around 1994 or ’95, first showed ten years later. I did not even imagine I could show it, but I showed it in the West ten years later.

Wachtel: And then you made it again in Lego.

Ai: Yeah, I made a very small edition and it sold very fast. Everybody asks about this. I was having a problem with the Lego company: they denied some of our approach, so I thought maybe I’d make an edition out of Lego.

Wachtel: But you continued to make art and architecture. In 2008, you were the design consultant with Herzog & de Meuron, the Swiss architects, for the Beijing National Stadium. And by the time the Olympics opened, you were already an outspoken critic of the Chinese government, in particular how it handled the May 2008 earthquake in Sichuan that killed almost ninety thousand people, including more than five thousand schoolchildren. Your response to the earthquake was remarkable. Could you tell me what you did?

Ai: When real tragedy happens, I become stoned. I don’t really know how to deal with it. I had no understanding of the earthquake. I didn’t know what really happened, but I decided to go to the site, to just travel to the area with my assistant, Zhao Zhao. I said, “Let’s go. Just bring a camera and see.” While standing in these ruins, and under those are bodies of schoolchildren, and there’s no way they can pull them out, and you sense the death in the wind, you start shaking. It’s a very strange feeling. I never had this kind of feeling before. Then I said, “I have to find out who is dead.” This was the first thing, to find out the truth. So we made an inquiry with the state, and they said, “No, come on. You’re joking. This is a state secret. You must be a spy or something.” I said, “Oh come on, I have put recordings on my blog, and I said to my blog followers I want to do a personal investigation.” They said, “Weiwei, what are you going to do, and when are you going to stop?” I said, “I will only be able to stop when I find out the full truth or when someone stops me.” We started to send our volunteers to the location, to families, to villages, to very remote areas in the mountains. And the volunteers were arrested more than a few thousand times. Police would take their research, tear up their papers, erase the names, and take their photos. But still, we managed, with the families, to find more than five thousand students, their birthdays, their names, their parents’ names, which school they went to. This was amazing. We created the first civil disobedience to search for the truth, and we did it successfully. Today, it’s not as possible, but the government still doesn’t know how to stop it. They’re not in total control of the internet. We have to find a language, find a form, find a way to release our confusion, anger, or anxiety and to be more clear, to come up with some kind of solution.

Wachtel: You also made several artworks in response to the earthquake. For example, Straight, which is made of the rebar from collapsed buildings, bent and twisted, these are the steel bars used to reinforce concrete. You bought these clandestinely, you had them straightened and arranged in a massive undulating sea, or a bit like a bird’s-eye view of a dried riverbed, or even a piece of land art. What kinds of thoughts were going through your head when you came up with the idea for Straight?

Ai: I was so desperate. I said, “First, I have to get all those rebars because in those ruins you only see two things: one is that twisted rebar, another is students’ backpacks.” I thought, I have to do something to them because very soon those rebars will be collected and sent to the factory and melted to recast into something else. So we managed it. It took quite a long time, I think two years, to get those rebars from a school where fifteen hundred students were crushed called Wenchuan Zhong Xue. And I sent them back to Beijing, and I stayed there. I didn’t know what to do with them. It’s such a strange thing to look at. I said, “Maybe the first thing we can do is straighten them up.” We started hiring a lot of workers just to straighten them one by one, each rebar needing to be hammered a few hundred times to straighten it. Then I got arrested. The first thing I heard when I came out from my detention and walked toward my studio was the sound of the banging.

Wachtel: The hammering.

Ai: Hammering. I was so happy in that moment. I was just so happy. Then we got that work done. And I think it’s a proper language: not too much, not too sentimental, not too dramatized. It just left us, like it just came out of a factory.

Wachtel: But like much of your work, Straight is both beautiful and highly critical, powerful. I know your activism is inextricable from your art, but how important is beauty for you?

Ai: I think beauty is everything. Beauty is the way we understand our world. Beauty is how we find a comfortable mental condition in dealing with this very cold so-called reality. We can find warmth and temperature and we can find expression in beauty. But beauty is very often misused as something very superficial, just to please your eye, with no deeper meaning or more profound meaning.

Wachtel: When you were held for eighty-one days, I read that your interrogators kept asking what your occupation was, and when you said artist they wouldn’t accept it, that anyone can be an artist. At most you’re an art-worker. Why do you think the idea of artist was so difficult for them to accept, or even threatening?

Ai: I think, first, “artist” doesn’t belong to any other category. It’s very hard to regulate what an artist is thinking because the artist is today’s philosopher. In most cases, artists don’t really play that role, but I think the artist is a philosopher, constantly asking questions and being subversive and not easily accepting old definitions. All those traits are extremely dangerous to authoritarians.

Wachtel: You did a powerful work about your eighty-one days in captivity called S.A.C.R.E.D., made up of six metal boxes, that on the outside looks, I don’t know, like a Donald Judd sculpture, but each has a step and the viewer climbs up to look into a box through a small window in the ceiling, and inside are these claustrophobic dioramas of scenes from your life in captivity, but half-size to scale. And you’re eating or sleeping, being interrogated even, going to the toilet, and these two uniformed guards are very present in the cell, very close to you. What did you want viewers to take away from this piece?

Ai: Merely to experience the same situation because people are always shy, but they still want to see what really happened. I said, “Okay, if I have to explain to my mom, my sister, or my son, why don’t I just recreate the situation?” It’s so easy just to reflect it. The work is not even made perfect, it doesn’t exactly reflect the kind of harshness, but I purposely reduced it to half-size so the situation is softened and people can see it more as a play.

Wachtel: As a play, but I know that you were still held, that you weren’t allowed to leave China, that the show was smuggled out to the Venice Biennale and your mother went to see it, and that she wept when she saw it.

Ai: Yeah, my mom could never imagine what she saw. I guess it’s not proper even letting my mom see it, but my mom’s a strong lady, and she had been through it with my father for so long, and he would have never imagined either that his son would be put in a more harsh situation.

Wachtel: That’s what I was thinking, that it evoked the time when you and her were in the labour camp with your father, that seeing those images of you being held in captivity . . .

Ai: I guess it’s very hard for any mom to see the situation. I’m so old, but still my mom will think of me as her son.

Wachtel: You were given your passport a year and a half ago. I know you’ve been spending quite a lot of time in Berlin, but you’re still based in China. What keeps you there? Can you imagine living elsewhere?

Ai: Oh, it’s my nation. It’s really my language, my family’s there, my father. It’s really my nation, you know. I mean, that’s the place that I am used to, and I know so many people . . .

Wachtel: What future for your son do you see there?

Ai: I don’t think he needs to be there. I should not speak for him, but I purposely push him out because I don’t want him to repeat my life. And that’s also why I fight—because I don’t want anybody to repeat my life.

Eleanor Wachtel is the host and co-founder of CBC Radio’s Writers & Company, now in its twenty-seventh season. She has also published five books of interviews, most recently The Best of Writers & Company (Biblioasis).