The germ of Brick was the review section of a short-lived literary magazine from London, Ontario, called Applegarth’s Folly. Joshua Applegarth was the first European settler in the London area, then the first to leave. For the magazine’s southwestern-Ontario publisher-editors, that was folly. But after they had published two issues of Brick, A Journal of Reviews, their brave, underfunded publishing operation foundered, and they too left town. Brick 1, published in 1977, opened with an editorial about the magazine’s name and about how reviewing should and could be improved. How many readers saw that? Maybe a dozen. Talk about hollering down a drainpipe! Here, revised, is the nub of that editorial:

1.

London, Ontario, where Brick began, is white brick, or yellow brick, or buff brick, depending on who describes it. When I first arrived there, from Alberta via Kingston, Ontario (gorgeous limestone buildings), I took a dislike to that white brick. It seemed to weather so dirty. Even when it was sandblasted, I couldn’t seem to take to it. I wasn’t really taking to London, either.

Summer of 1970, I found myself taking pictures of brick walls in downtown London, behind the stores where we don’t ordinarily go. What I started out to get was something I had gradually grown interested in: outlines on the walls of brick buildings, left by other buildings that had been torn down. You can often read something of a vanished building from the imprint left behind: floor, staircase, roof, window. Possibly the outlines are clearer on white brick than on red, but I don’t remember taking any special interest in the brick itself, not at first. Then I found myself getting closer and closer to the walls, as close as my Pentax K1000 permitted. I began to see colours, pastels that fade out in the long view: green, pink, red, orange, brown. Different textures: new brick, weathered brick, crumbling brick, painted brick, painted and peeling brick, arched windows bricked in, iron braces bracing brick. Wherever I aimed, even here and there at the same wall, the viewfinder framed a different picture. Aware of all those differences, then, I could move back and see that whole walls of what I had been calling white brick, and disliking, are quite individual in colour mix and texture. The term no longer meant what it had, and the city got more interesting. To get to where I could see, I had to eliminate context: building first, then wall.

2.

Brick has a watchword from Rainer Maria Rilke as quoted by e. e. cummings, in i: six nonlectures: “Works of art are of an infinite loneliness and with nothing to be so little reached as with criticism. Only love can grasp and hold and fairly judge them.” “In my proud and humble opinion,” cummings remarks, “those two sentences are worth all the soi-disant criticism of the arts that has ever existed or will ever exist. Disagree with them as much as you like, but never forget them; for if you do you will have forgotten the mystery which you have been, the mystery which you shall be, and the mystery you are.”

The loving reader wants a book to succeed with her, so she gives it every chance. She wants to succeed with the book so tries hard to find out its terms. To the book she brings all she is, all she knows, but on all that she hangs fire so her initial response may be as innocent as possible. The pure reader is in there on her own, open as they come, tough as she needs to be. She is always herself, has nothing to prove. She is freer than you and I.

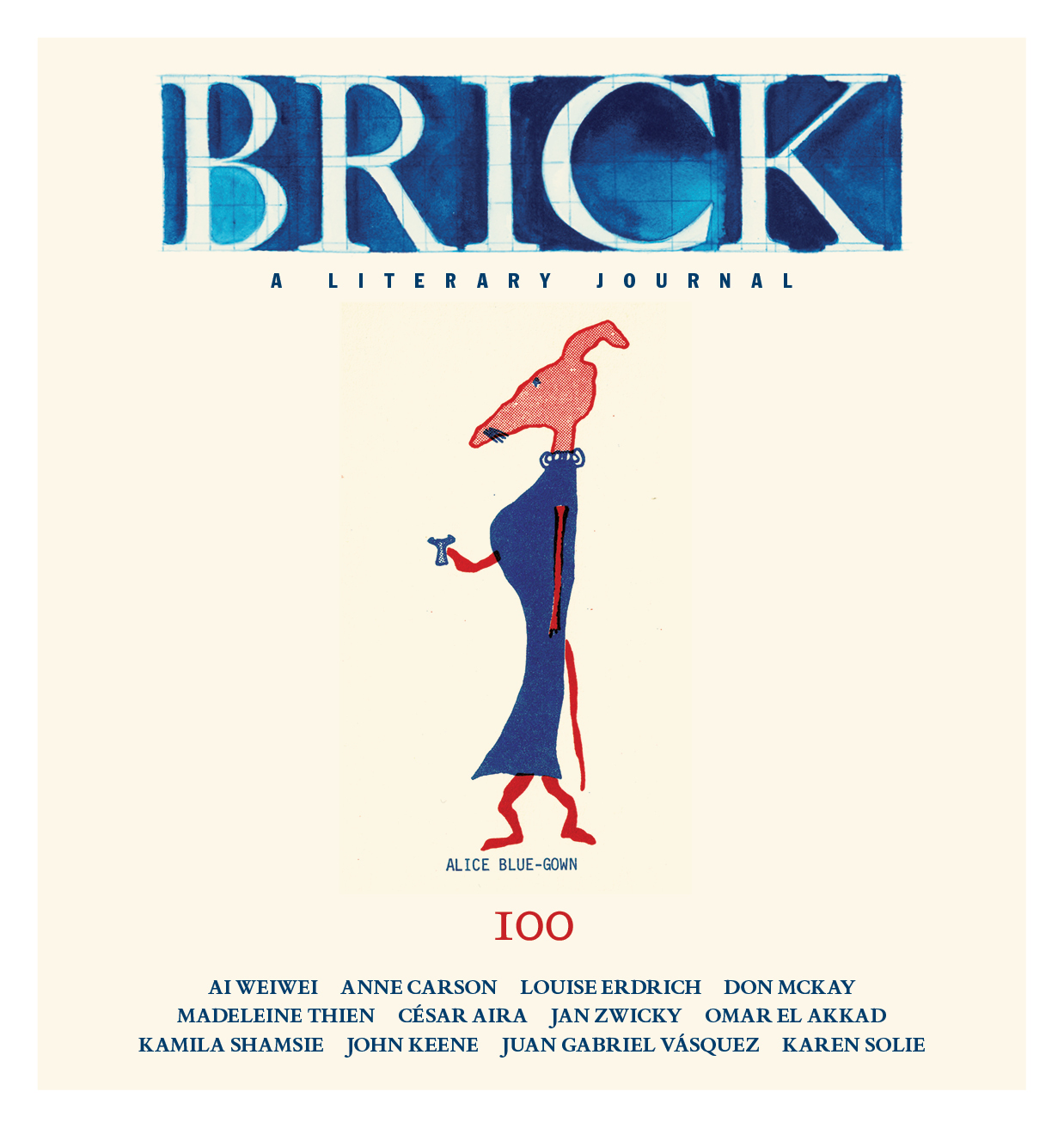

Jean McKay and I kept on with Brick until issue 24. We had fun pasting up the magazine, illustrating the essays with pictures and design elements cut out of old books and magazines. I still have a fondness for the strange look of those first twenty-four Bricks. Non-designer that I am, why wouldn’t I? But the writing was always good. We insisted on that. Number 25 was edited by Linda Spalding. Under her, and then a series of other fine editors, Brick evolved into the eclectic international literary magazine it now is—properly designed! A review section graces recent issues. Back to the roots.

I never cared to love works of art and leave it at that. Like so many of the writers I read in Brick, I want love carried into criticism. I believe Rilke would be okay with that, and I’m glad Brick has printed his words in every number for forty years. I’m still worrying the issue of reading, as in the following excerpt from The Bricoleur and His Sentences. It’s offered here as a salute to the ongoing enterprise of Brick, still driven by love and, if you can go by me, much loved by readers.

Lost is where I like to be in reading. I like to follow a path of words with anticipation and without expectation. Receptivity, says Louise Glück, “begins with the self’s effacement.” It’s a pretense, she says, because “the self without ‘selfish bias’ doesn’t exist” but is a workable and enabling ruse nevertheless. “So for the moment, [the mind] suspends opinion and response, all the means by which it has so long struggled to define itself, attempting, instead, neutrality, attentiveness; for the moment, it plays dead; only a very deep confidence in literature’s power allows this, and only the training in pretense allows the birth of such confidence.” Despite all I have been taught about how to read I still have the sensation of reading as when I was a child: voraciously, wonderingly, gratefully—though now it’s a text with soul that’s most likely to grab me and hold. There is no perfect reader, but my sort avoids what Glück calls “the repeating limitations of the single self, which projects onto literature a dispiriting sameness, an absence of any real variety.”

Overdue apologies to all those who thought Brick must be an acronym: Book Review . . . Nope.

Stan Dragland lives in St. John’s, Newfoundland. His most recent book is a novel, The Drowned Lands, from Pedlar Press. Along with Jean McKay, he was the founder of Brick.